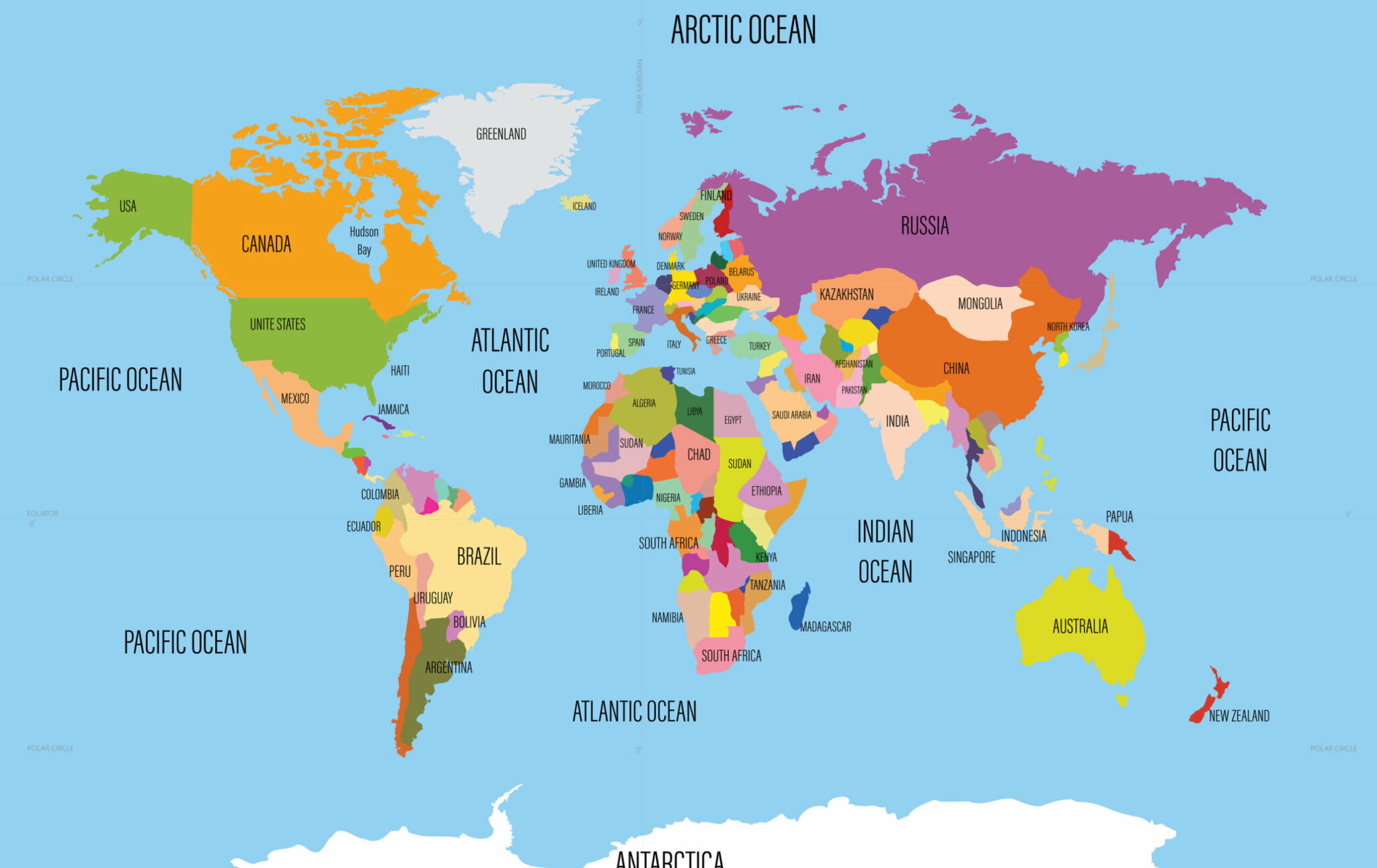

You probably think you know exactly what the world looks like. You've seen the posters in classrooms. You've scrolled through Google Maps to find your own house. But here is the thing: every map of world with continents and oceans you have ever looked at is, by definition, a lie. It’s a flat representation of a curved reality. That causes some weird distortions. Greenland is not actually the size of Africa, and Mercator has been messing with your head for years.

Geography is weird. It’s also constantly changing. We used to talk about four oceans, but now there are five. We used to think continents were these permanent, unmoving slabs of rock, but they are basically giant rafts drifting on a sea of molten mantle. If you really want to understand the planet, you have to look past the blue and green shapes on the paper.

The Problem with Flattening the Globe

The biggest issue with any map of world with continents and oceans is the "orange peel" problem. Imagine taking an orange, drawing the continents on it, and then trying to flatten that peel onto a table without tearing it. You can't do it. To make it flat, you have to stretch the top and the bottom.

This is why the Mercator projection—the one we all use—makes Europe and North America look massive while shrinking the tropics. In reality, Africa is nearly 14 times larger than Greenland. On most maps, they look about the same size. It’s a bit of a colonial leftover that still dictates how we perceive global importance.

Why Projections Still Matter

Gerardus Mercator didn't design his map to be a classroom tool; he designed it for sailors in 1569. It keeps lines of constant bearing straight, which is great if you’re trying to navigate a ship across the Atlantic with a compass. It sucks if you’re trying to teach a kid the actual scale of South America.

We have other options now. The Gall-Peters projection shows the correct sizes but makes the continents look like they’ve been stretched out like taffy. Then there’s the Robinson projection, which tries to find a middle ground by compromising everything just a little bit. It doesn’t get anything perfect, but it looks "right" to the human eye.

👉 See also: Why the Man Black Hair Blue Eyes Combo is So Rare (and the Genetics Behind It)

Defining the Seven (or Six, or Five) Continents

We are taught there are seven continents: Asia, Africa, North America, South America, Antarctica, Europe, and Australia. Simple, right? Not really.

The definition of a "continent" is surprisingly loose. Geologically, Europe and Asia are one single landmass called Eurasia. There’s no ocean between them, just the Ural Mountains, which honestly aren't even that tall. If you live in Russia or many parts of Eastern Europe, you were probably taught they are one continent.

Then you have the Olympic rings, which represent five continents because they exclude Antarctica (since nobody lives there permanently) and combine the Americas into one.

The Mystery of Zealandia

Here is a fun one for your next trivia night: there might actually be eight continents. Scientists have been arguing for years that Zealandia—a massive 4.9 million square kilometer slab of continental crust—should be recognized.

Most of it is underwater. Only New Zealand and New Caledonia poke above the waves. But it meets all the criteria: it’s elevated above the surrounding ocean floor, it has a distinct geology, and it’s thicker than the regular oceanic crust. It’s a reminder that our map of world with continents and oceans is just a snapshot of a specific moment in geologic time.

✨ Don't miss: Chuck E. Cheese in Boca Raton: Why This Location Still Wins Over Parents

The Five Oceans and Why the Names Changed

For a long time, the world was simple: Atlantic, Pacific, Indian, and Arctic. That was it. But in 2021, the National Geographic Society officially recognized the Southern Ocean as the world's fifth ocean.

The Southern Ocean is the water surrounding Antarctica. It’s unique because it isn't defined by the land that surrounds it, but by a current. The Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC) flows from west to east around the frozen continent. This water is colder and less salty than the waters to the north.

- The Pacific: The big one. It covers about one-third of the Earth's surface. You could fit all the world's landmasses into the Pacific and still have room left over.

- The Atlantic: It’s growing. Literally. The Mid-Atlantic Ridge is pushing the Americas away from Europe and Africa at about the rate your fingernails grow.

- The Indian: The warmest of the bunch. It’s also historically the most important for ancient trade routes.

- The Arctic: The smallest and shallowest. It's also the most vulnerable to climate change as the ice cover thins.

- The Southern: The "new" kid. It’s defined by its ecological isolation and fierce winds.

How Tectonics Keep the Map Moving

If you look at the coastlines of South America and Africa, they fit together like a puzzle. Alfred Wegener noticed this back in 1912 and came up with the idea of Continental Drift. People thought he was crazy. They asked, "How does a whole continent just move?"

We now know about plate tectonics. The Earth’s crust is broken into plates that "float" on the semi-liquid asthenosphere.

When you look at a map of world with continents and oceans, you are looking at a temporary arrangement. About 300 million years ago, all the land was clumped into a supercontinent called Pangea. In another 250 million years, scientists predict we’ll have a new supercontinent, often called Pangea Proxima. The Atlantic will close up, and Africa will smash into Europe, wiping out the Mediterranean Sea and replacing it with a mountain range that will make the Himalayas look like foothills.

🔗 Read more: The Betta Fish in Vase with Plant Setup: Why Your Fish Is Probably Miserable

The Ring of Fire

The edges of these plates are where the action happens. The "Ring of Fire" around the Pacific Ocean is home to about 75% of the world's active volcanoes. It’s not a coincidence that the biggest ocean also has the most violent edges. This is where oceanic crust is being shoved under continental crust in a process called subduction. It recycles the Earth's surface.

Why the "Blue Marble" Perspective Is Rare

Most maps are centered on the Prime Meridian, putting Europe and Africa in the middle. This is the "Greenwich" view of the world. But if you live in Japan or Australia, your maps probably look different, with the Pacific in the center.

There is no "up" in space. There is no reason North has to be at the top of the map. South-up maps are perfectly valid, and they completely change how you view the relationship between countries. It makes Australia look like a massive capstone on the world and relegates the Northern Hemisphere to the bottom.

Surprising Facts About the World Map

Let’s talk about some things that don't seem right but are 100% true.

- The Panama Canal: Most people think the Atlantic is on the east and the Pacific is on the west. Because of the way Panama curves, a ship traveling from the Atlantic to the Pacific actually moves west to east.

- The Diomede Islands: There are two islands in the Bering Strait. One is Russian, one is American. They are only 2.4 miles apart. But because the International Date Line runs between them, the Russian island is 21 hours ahead of the American one. You can literally look across the water and see "tomorrow."

- Africa's Scale: Africa is so big that you can fit the USA, China, India, Japan, and most of Europe inside its borders simultaneously.

Actionable Insights for Better Map Literacy

Don't just rely on the map on your wall. If you want to actually understand the world, you have to vary your sources.

- Use a Globe: It is the only way to see true relative sizes. If you don't have a physical one, use Google Earth. It eliminates the distortions of flat projections.

- Try the True Size Tool: There’s a great website called thetruesize.com. It lets you drag countries around a map to see how big they actually are compared to others. Dragging the DR Congo over to Europe is an eye-opening experience.

- Look at Bathymetric Maps: These show the "map" of the ocean floor. The mountains and canyons under the water are often more dramatic than anything on land. The Mariana Trench is deeper than Everest is tall.

- Check the Legends: Always look at the scale and the projection type. If a map doesn't tell you its projection, be skeptical of the sizes you see.

The world isn't a static image. It's a vibrating, shifting, and shrinking place. Understanding the map of world with continents and oceans isn't just about memorizing names; it's about realizing how much the "standard" view of our planet is influenced by history, math, and a little bit of creative stretching.

To get a better grip on this, start by looking at a map centered on the South Pole or a Dymaxion map. It will break your brain for a second, but it'll give you a much clearer picture of how connected we actually are.