You’ve probably spent your whole life looking at a lie. Or, if not a lie, a very distorted version of the truth. Look at the wall of almost any classroom in the world and you’ll see it—the Mercator projection. It’s that classic map where Greenland looks like it’s the size of Africa and South America seems tiny compared to Europe.

It’s wrong. Totally wrong.

Actually, Africa is fourteen times larger than Greenland. You could fit the United States, China, India, and most of Europe inside the borders of Africa with room to spare. But on the maps we use for GPS and school textbooks, the map of world real proportions is sacrificed for the sake of straight lines and easy navigation.

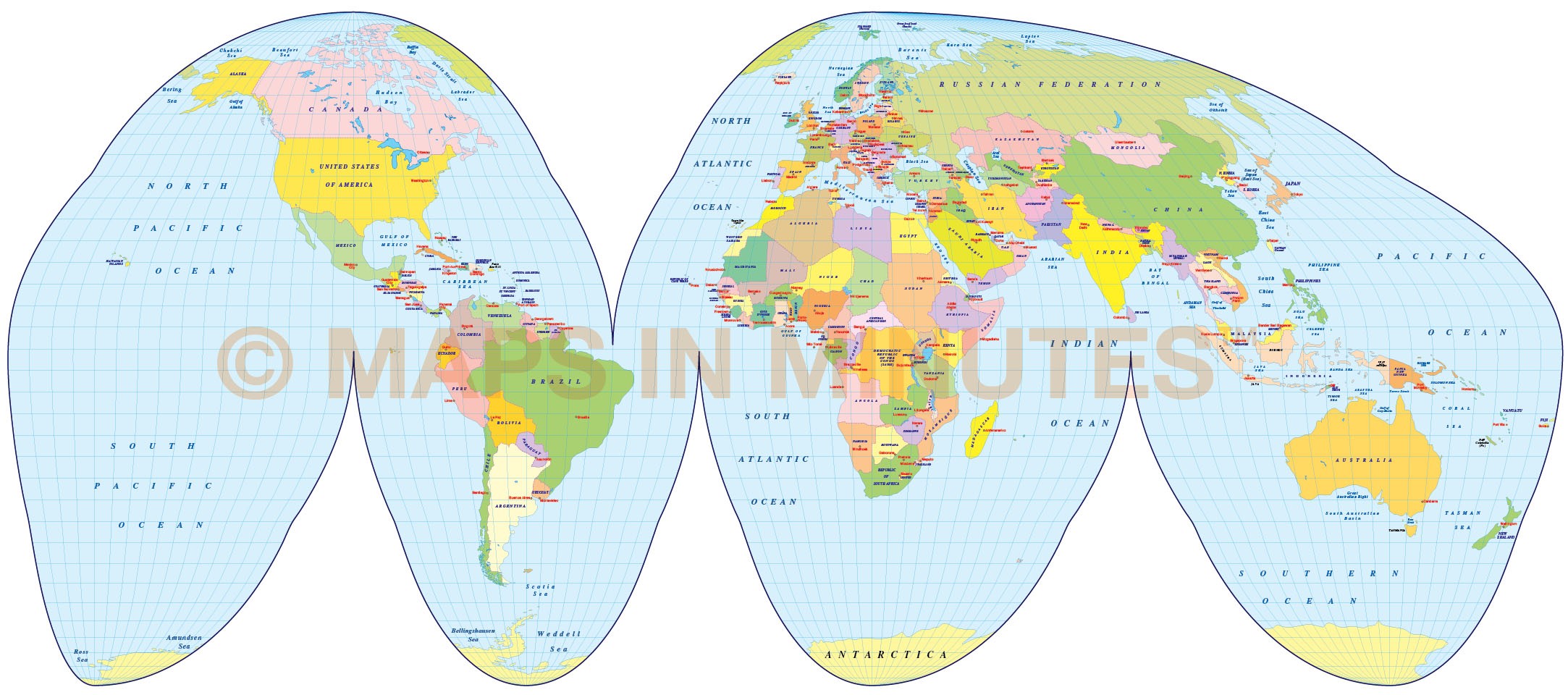

Maps are basically just math problems that nobody can solve perfectly. Think about it. You’re trying to peel an orange and flatten the skin onto a table without tearing it or stretching it. You can’t. Something has to give. In cartography, you either mess up the shapes of the countries, or you mess up their actual size. For hundreds of years, we chose to mess up the size.

The Mercator Problem and Why Your Brain Is Warped

Gerardus Mercator created his famous map in 1569. He wasn't trying to trick you. He was a navigator. He needed a map where a sailor could draw a straight line between two points and follow a constant compass bearing. That’s called a rhumb line. For sailors, this was a revolutionary piece of technology. It kept them from dying at sea.

But here’s the catch. To make those lines straight, Mercator had to stretch the map more and more as you move away from the equator.

The result? The "Great Britain effect." Countries in the northern hemisphere look massive, while tropical regions—mostly in the Global South—shrink. Alaska looks like it could swallow Brazil. In reality, Brazil is five times larger than Alaska. When we talk about a map of world real proportions, we are talking about unlearning a visual bias that has been baked into our brains since kindergarten.

It’s not just a trivia point. It changes how we perceive power. If a country looks bigger on a map, we subconsciously think it’s more important, more resource-rich, or more dominant. This is why the Gall-Peters projection caused such a massive stir when it started gaining popularity in the 1970s. It was a political statement as much as a geographical one.

Finding the Map of World Real Proportions: Gall-Peters and AuthaGraph

If you want to see the world as it actually exists in terms of square mileage, you have to look at "equal-area" projections.

🔗 Read more: Doppler Radar Fort Walton Beach: What Most People Get Wrong

The Gall-Peters projection is the most famous alternative. It keeps the sizes accurate. If Africa is bigger than North America, it looks bigger. Period. But there’s a downside—it looks like someone took the continents and put them in a taffy puller. Everything is stretched vertically. People hate it because it looks "ugly," but it’s technically more "honest" about landmass.

Then there is the AuthaGraph.

Created by Japanese architect Hajime Narukawa in 1999, the AuthaGraph is widely considered the most accurate map of world real proportions ever made. Narukawa basically divided the globe into 96 triangles, projected them onto a tetrahedron, and then unfolded it. It’s weird. It doesn’t look like the map you’re used to. The oceans don’t look like vast empty squares. But it manages to preserve the correct proportions of all landmasses and seas while reducing the "stretching" effect you see in Gall-Peters.

Why doesn't everyone just use the AuthaGraph?

Because it’s hard to read. We’ve been conditioned to see North at the top and South at the bottom in a very specific rectangular grid. The AuthaGraph breaks that grid. It’s a tool for accuracy, not necessarily for quick glancing while you’re trying to find a coffee shop on your phone.

The Digital Shift: How Google Maps Changed the Game

For a long time, Google Maps actually used a version of the Mercator projection (specifically Web Mercator). They did this because it makes the streets look like 90-degree angles when you zoom in. If they used a more "accurate" projection, the buildings in London would look tilted compared to the buildings in Nairobi.

However, around 2018, Google rolled out a "3D Globe" mode for the desktop version. If you zoom out far enough, the flat map disappears and you’re looking at a sphere. This was a huge win for the map of world real proportions. Suddenly, users could see that Greenland is actually a relatively small island and not a continent-sized behemoth.

Modern Tools for Comparison

If you want to spend an hour having your mind blown, go to The True Size Of. It’s a web tool that lets you drag countries around a Mercator map. When you slide China over to the United States, you see they’re almost the same size. But when you slide India up to Europe, you realize India is basically a continent of its own. It’s the best way to visualize the map of world real proportions without needing a degree in cartography.

The Real Numbers (No Fluff)

To really grasp how much we've been misled, look at the actual surface area of these landmasses.

Africa sits at about 30.3 million square kilometers.

North America is roughly 24.7 million.

On a Mercator map, North America looks nearly double the size of Africa. In reality, you could put the USA inside Africa three times.

Look at Antarctica. On many maps, it’s a giant white bar at the bottom that seems to go on forever. It’s actually the fifth-largest continent, about 14 million square kilometers. It's smaller than Russia. But because it sits at the pole, Mercator stretches it to infinity.

Why Accuracy Matters in 2026

We live in a globalized economy. When we look at a map, we are looking at the stage where climate change, migration, and trade happen. If we use a distorted map, we develop a distorted view of where the world's challenges are located.

For example, when we look at the size of the Pacific Ocean on a real-proportion map, we realize just how massive the "Blue Economy" is. It’s not just a gap between America and Asia; it’s a staggering percentage of the planet’s surface.

There’s also the psychological element. Dr. Arno Peters, who championed the Gall-Peters map, argued that the Mercator projection was a form of "cartographic imperialism." By shrinking the equator and enlarging the poles, you are literally making the formerly colonized world look smaller and less significant. Whether you agree with his politics or not, the math doesn't lie: our visual representation of the Earth is biased toward the north.

📖 Related: Why the iPhone 5 Lightning Cable Changed Everything (and Why It’s Still a Pain)

Actionable Steps for the Curious

If you’re tired of looking at a distorted world, here is how you can actually start seeing things clearly:

- Switch your view. Open Google Maps on a desktop and zoom all the way out until it becomes a globe. Rotate it. Look at the southern hemisphere for five minutes. It will feel "upside down" or "wrong" because of your training, but that's what the planet actually looks like.

- Buy a Dymaxion Map. Designed by Buckminster Fuller, this map projects the world onto an icosahedron. It has no "up" or "down" and shows the continents as a nearly contiguous island in one giant ocean. It’s the best way to see how connected we actually are.

- Use "The True Size Of" tool. Search for it online. Drag your home country to the equator and then drag it to the North Pole. Watch it grow and shrink. It’s the fastest way to un-distort your brain.

- Check out the Winkel Tripel. If you want a compromise between "real size" and "real shape," this is the projection used by the National Geographic Society. It’s not perfect—no flat map is—but it’s one of the most honest representations we have that still looks like a "map."

The map of world real proportions isn't just one single image. It’s a way of understanding that every map is a choice. When you choose a map, you're choosing what to prioritize: direction, shape, or area. In a world that's more connected than ever, it's probably time we started prioritizing the truth about how much space we all actually take up.