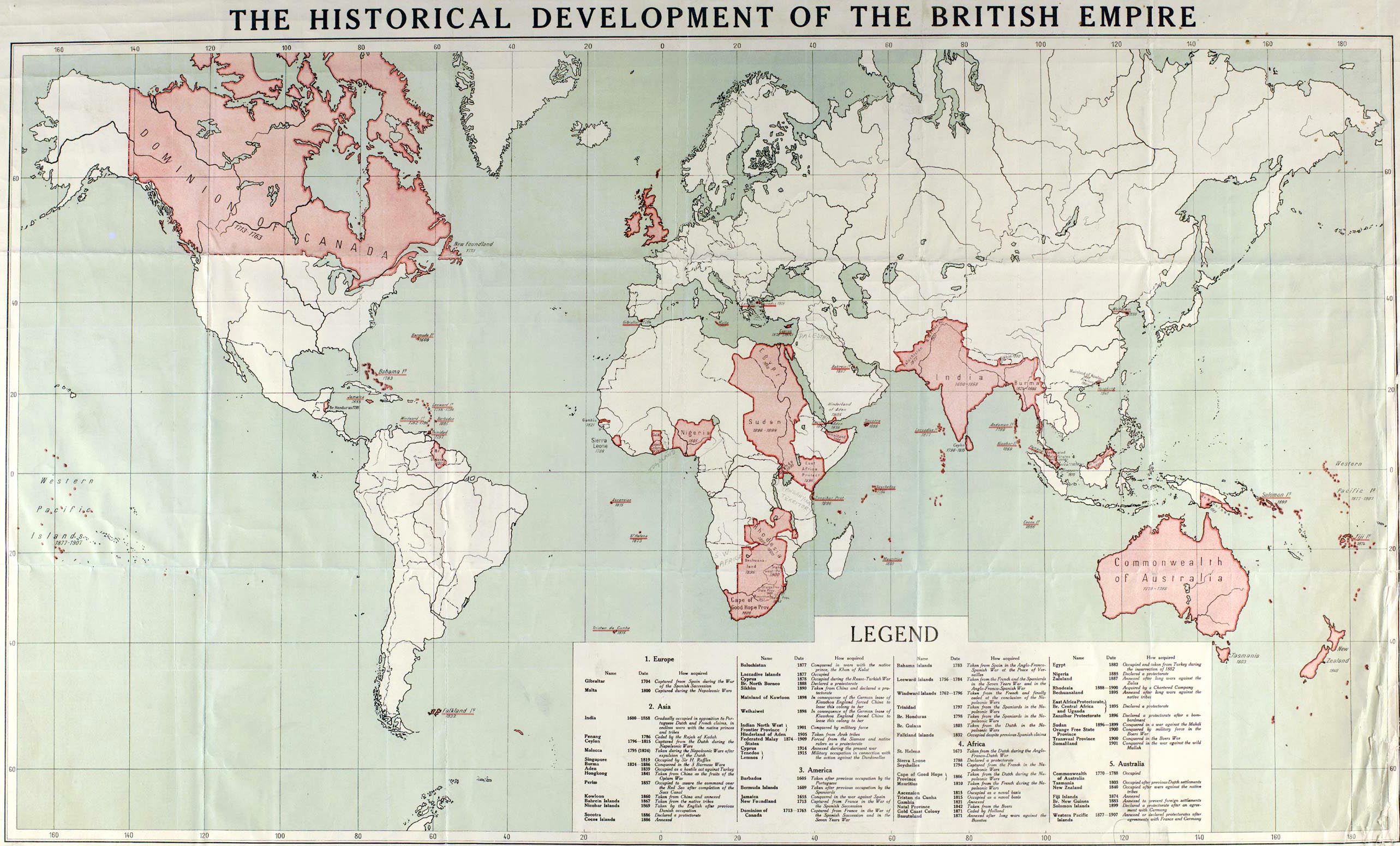

Ever looked at those old schoolroom posters where half the world is splashed in bright, unapologetic pink? That’s the classic map of the British Empire. It’s an image that sticks in the brain. It looks solid. It looks like a singular, massive block of power that owned the 19th and early 20th centuries. But honestly, if you actually dig into the cartography of that era, you realize those maps were doing a lot of heavy lifting for the PR department in London.

The map was a lie. Or at least, a very creative interpretation of reality.

When we talk about the British Empire at its height, usually around 1921, we’re talking about roughly 13.7 million square miles. That is about a quarter of the Earth's land area. It’s huge. But the way those maps were drawn—often using the Mercator projection—made Canada and Great Britain look significantly larger than they actually were relative to Africa or India. It wasn't just about geography; it was about the psychology of space. If you were a kid in a London classroom in 1900, looking at that map gave you a sense of inevitable "Britishness" spreading across the globe.

The Mercator Trap and the "Red Line"

Why pink? Or red?

Cartographers like Stanford’s or the makers of the Bartholomew’s Handy Reference Atlas didn't just pick the color because it looked nice against the blue of the oceans. It became a standardized branding. In the late 1800s, "the thin red line" wasn't just a military term; it was a visual promise. If a territory was pink, it meant British law, British steamships, and British telegraph cables were supposed to be there.

But here is the thing: a map of the British Empire rarely showed the "informal empire."

Historians like John Gallagher and Ronald Robinson famously argued that the real power of Britain wasn't just in the colored-in bits. It was in the places they didn't officially own but effectively controlled through debt, trade, and naval pressure. Think of Argentina in the 1880s. It wasn't pink on the map. Yet, British banks owned the railroads, British engineers built the docks, and the British pound was the lifeblood of the economy. If you only look at the colored sections of a map, you’re missing half the story of how global power actually functioned.

📖 Related: What Does a Stoner Mean? Why the Answer Is Changing in 2026

The maps were also remarkably static. They didn't show the constant flux. They didn't show the "Frontier Wars" in South Africa or the resistance in the North-West Frontier of India. A map makes a border look like a permanent, sharp line. In reality, those borders were often porous, disputed, or completely ignored by the people living there.

How the Map of the British Empire Was Actually Built

It wasn't just explorers with pith helmets wandering into the bush. It was a massive data-gathering exercise. The Great Trigonometrical Survey of India, started in 1802 by William Lambton and continued by George Everest, is one of the most insane technical feats in human history. They spent decades hauling massive, half-ton theodolites up mountains to measure the subcontinent with inch-perfect accuracy.

They wanted to "know" the land so they could tax it. That’s the gritty reality behind the beautiful aesthetics of an antique map.

Mapping was a tool of administration. Once you have a map, you can divide land into plots. You can build a railway. You can move troops effectively. This is why the map of the British Empire is so fascinating to modern historians—it's a snapshot of an attempt to organize the entire world according to a single set of rules.

But look closer at a map from, say, 1897—Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee. You’ll see names that don’t exist anymore. Bechuanaland. Ceylon. The Trucial States. Nyasaland. These names were often slapped onto regions by colonial administrators who barely understood the local ethnic or linguistic boundaries. The "Map of Africa" created at the Berlin Conference in 1884-85 is the ultimate example of this. Men in a room in Germany drew lines on a map of a continent they had mostly never visited. They used rulers. They ignored rivers, mountains, and tribal territories. We are still dealing with the fallout of those straight lines today in the form of modern border disputes.

Layers of Control: It Wasn't All One "Empire"

One common misconception is that everything in pink was ruled the same way. It wasn't. The map of the British Empire was a messy patchwork of different legal statuses.

👉 See also: Am I Gay Buzzfeed Quizzes and the Quest for Identity Online

- Crown Colonies: Ruled directly by London (like Hong Kong or Jamaica).

- Protectorates: Local rulers stayed in place, but Britain handled the "big stuff" like defense and foreign policy (like many parts of Africa).

- Dominions: Basically independent countries that still liked the Queen and the trade perks (Canada, Australia, New Zealand).

- Princely States: In India, there were hundreds of these. They weren't "British" in the sense of direct rule, but the British "Resident" was always there, whispering in the Ear of the Maharaja.

If you tried to map this accurately with different colors for every type of relationship, the map would be an unreadable kaleidoscopic nightmare. So, they just used pink. It simplified a very complicated reality into a single, digestible "brand."

The Telegraph: The "Nervous System" of the Map

By the 1870s, the map started to feature something new: thin black lines snaking across the oceans. These were the submarine telegraph cables. This is where the empire became "modern."

Before the cable, a message from London to India took weeks by ship. After the "All-Red Line" (a network of cables that only touched British territory) was completed, it took minutes. This changed how the empire was managed. It meant London could micromanage governors on the other side of the planet. It also meant that the map became a network rather than just a collection of territories.

If you find a map from 1902 that shows these cable routes, you’re looking at the Victorian version of the internet. It was about connectivity and speed. The British were obsessed with being the "hub" of the world's information.

What the Map Doesn't Tell You

Maps are as much about what they hide as what they show.

A standard map of the British Empire doesn't show the famines in Bengal. It doesn't show the displacement of Indigenous populations in Australia. It doesn't show the concentration camps during the Boer War. It presents the empire as a clean, finished product.

✨ Don't miss: Easy recipes dinner for two: Why you are probably overcomplicating date night

There's a famous 1886 world map by Walter Crane. It’s incredibly ornate. It has illustrations of people from all over the empire in the margins—Indians, Africans, Australians—all looking happily toward Britannia. It’s pure propaganda. It was meant to make the British public feel proud and secure. But if you look at the actual history of that year, the empire was facing massive internal pressures. The map was a mask.

Why We Still Look at These Maps

There is a weird nostalgia for the aesthetics of the old map of the British Empire. You see them in bars, libraries, and as "vintage" decor on Etsy.

Part of it is just the design. The typography of the 19th century was gorgeous. The hand-colored tints have a warmth that digital maps lack. But part of it is the scale. It represents a time when the world felt "discovered" and yet still vast.

For many people in the UK, the map is a source of complicated identity. For people in former colonies, the map is a record of a border they might still be fighting over. It’s not just paper; it’s a political document that still has "teeth" in the 21st century.

How to Actually Study an Empire Map

If you’re looking at one of these maps today—whether it's for a history project or just because you’re a map nerd—don't just look at the pink.

- Check the Projection: Is it Mercator? If so, look at how much bigger Greenland looks compared to Africa. Now you know why the British felt so dominant.

- Look for the Ports: Notice how many pink spots are just tiny islands. These were "coaling stations." The empire was built on steam, and steam needs coal. Places like Aden, Gibraltar, and Singapore were the "gas stations" of the 19th century.

- Find the Railways: In Africa and India, look at where the lines go. Usually, they don't connect cities to help people travel; they connect mines or farms to the coast so resources can be shipped to London.

- Read the Marginalia: The notes in the corners often list populations and trade exports. This tells you what the British actually valued in that specific colony. Was it sugar? Cotton? Rubber?

Actionable Insights for Researching Colonial Maps

If you want to go deeper than a Google Image search, there are better ways to see the real map of the British Empire.

- Visit the British Library’s Online Map Room: They have high-res scans of the actual working maps used by the Colonial Office. These often have handwritten notes that are much more revealing than the printed versions.

- Compare "Ethnic Maps" vs "Political Maps": Find a map from 1900 that shows tribal boundaries and overlay it with a British political map. The "mismatch" tells you exactly where future conflicts were born.

- Look for the "Gaps": Research the "Princely States" of India. You’ll find that a huge chunk of the subcontinent wasn't technically British. This completely changes your perspective on how "total" their control really was.

- Trace the Telegraph Cables: Mapping the "All-Red Line" shows you the first global communication network. It explains why London became the financial capital of the world—they got the news first.

The map of the British Empire is a fascinating, beautiful, and deeply problematic artifact. It’s a vision of the world as one small island wanted it to be, not necessarily how it was. By looking at it critically, you stop seeing just "pink bits" and start seeing the machinery of a global system that shaped the modern world for better and for worse.