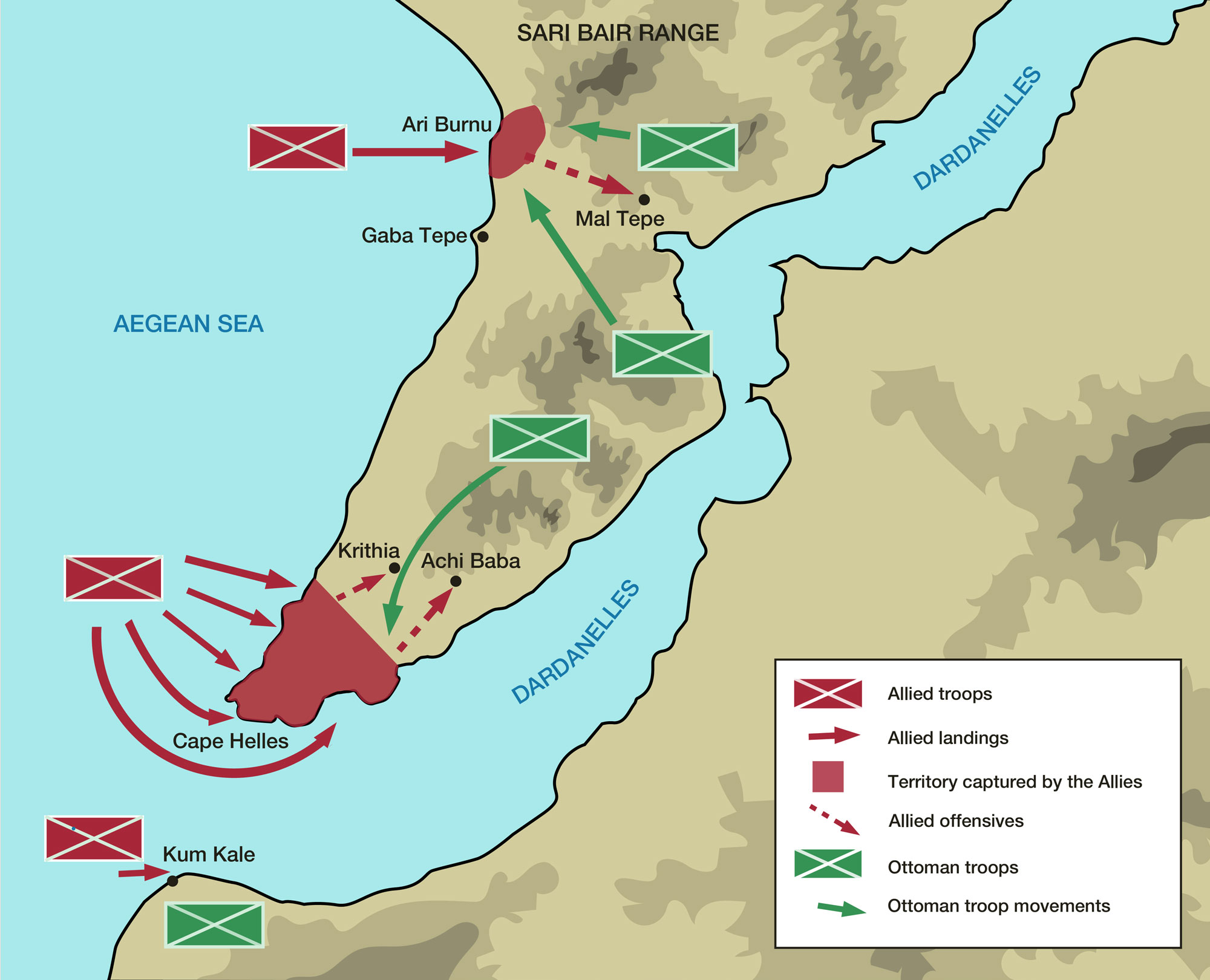

Maps aren't just paper. They're dreams of how a war is supposed to go, and at Gallipoli, those dreams were basically nightmares. If you look at a map of the Battle of Gallipoli today, it looks orderly. You see blue lines for the Allies, red or green for the Ottoman Empire, and neat little arrows showing where people were supposed to walk.

It was a mess.

Honestly, the British High Command went into this using old, inaccurate Greek maps and tourist charts. Can you imagine? Attempting one of the most complex amphibious landings in history with a map that didn't show the actual height of the ridges you had to climb. They thought the terrain was a gentle slope. It was a cliff.

The ANZAC Cove Error: Why the Map Didn't Match the Shore

On April 25, 1915, the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC) hit the beach. But they weren't where they were supposed to be.

Most historians, like Les Carlyon in his massive tome Gallipoli, point out that the current pulled the boats north. Instead of a nice, wide beach at Brighton Beach, they slammed into a tiny, narrow strip of sand overlooked by jagged, vertical terrain. This spot is now known as ANZAC Cove. If you look at the map of the Battle of Gallipoli from that morning, the gap between the intended landing zone and the actual one is only about a mile, but in trench warfare, a mile is an eternity.

The soldiers looked up and saw the Sphinx. Not the one in Egypt, but a towering rock formation that shouldn't have been their first obstacle. Because the map was wrong—or the navigation was—the plan broke instantly.

Imagine 15,000 men crammed into a space the size of a few football fields, with Turkish marksmen looking straight down at them. There was no "front line" for the first few hours. Just chaos.

The Suvla Bay Map Failure

By August, the British tried again further north at Suvla Bay. They had better maps by then, or so they thought. General Stopford, the man in charge, decided to wait on the beach.

✨ Don't miss: The CIA Stars on the Wall: What the Memorial Really Represents

The map showed the hills were empty. They were.

If the British had moved, they could have taken the heights of Tekke Tepe before the Ottomans arrived. But they didn't. They sat on the sand, made tea, and waited for orders. By the time the map was translated into movement, Mustafa Kemal (later Atatürk) had rushed Ottoman reinforcements to the ridges. The window slammed shut.

It’s one of the greatest "what ifs" in military history. A quick glance at the topography on a modern map of the Battle of Gallipoli shows that Suvla was the soft underbelly. But maps don't account for human hesitation or the sheer heat of a Turkish summer that turns a map into a sweat-soaked piece of useless pulp.

Deep Gullies and Dead Ends

The terrain at Gallipoli is a labyrinth. It’s all "ders" (valleys) and "tepes" (hills).

- Monash Gully: A terrifying funnel where snipers ruled.

- The Nek: A tiny strip of land no wider than a tennis court.

- Lone Pine: A plateau where the fighting was hand-to-hand in dark tunnels.

In these places, a map was almost useless. The trenches were so close—sometimes only 10 yards apart—that you couldn't draw them as separate lines. You had to draw them as a single, tangled knot. You’ve got to realize that the soldiers often didn't know which way was north once they were in the maze.

The Ottoman Perspective: Mapping Home Turf

We often talk about the British or Australian maps, but the Ottoman maps were different. They knew the "Sheep Track" and the hidden wells.

Mehmet Fasıl, an Ottoman officer, wrote about how they used the ridges as a natural fortress. Their map of the Battle of Gallipoli wasn't just topographical; it was tactical. They didn't need to see the whole peninsula. They just needed to hold the high ground at Chunuk Bair.

🔗 Read more: Passive Resistance Explained: Why It Is Way More Than Just Standing Still

When you stand at the top of Chunuk Bair today, you can see both sides of the peninsula. You see the Aegean Sea to the west and the Dardanelles to the east. That’s why that tiny patch of dirt on the map was worth thousands of lives. If the Allies took that ridge, the Ottoman capital, Constantinople, was wide open. They never took it.

Why Scale Matters (And Why It Failed)

Scale is a funny thing. On a 1:40,000 map, a gully looks like a wrinkle. In real life, that wrinkle is a 200-foot drop filled with thorny scrub that tears your uniform to shreds.

The British 29th Division at Helles (the southern tip) had a "clear" map of the beaches. But the map didn't show the underwater barbed wire. It didn't show the hidden machine-gun nests carved into the rock. When the River Clyde (a converted collier ship) grounded at V Beach, the map said "land here." The reality was a slaughterhouse.

Modern Ways to View the Battlefield

If you're trying to understand this today, don't just look at a flat image.

- LiDAR Scans: Researchers have used light detection and ranging to "see" through the bushes. They’ve found miles of trenches that aren't on any 1915 map.

- Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC): Their maps show where the cemeteries are now. Often, the cemeteries are located exactly where the most confusing parts of the map were—the places where people got lost and trapped.

- Google Earth: Honestly, it’s the best way to see the "impossible" terrain. Tilt the view. Look at the heights of Sari Bair. It looks terrifying even from a satellite.

The Evacuation: The Only Map That Worked

Ironically, the best-mapped part of the campaign was the exit.

In December 1915 and January 1916, the Allies pulled off a miracle. They left without losing a single man. They used "drip rifles"—rifles rigged with leaking cans of water that would fire periodically to make the Ottomans think the trenches were still full.

The evacuation maps were meticulous. Every unit had a timed route. Every pier had a capacity limit. It was the only time the paperwork and the reality actually aligned. It's a bit grim, isn't it? The only thing they mapped perfectly was how to give up.

💡 You might also like: What Really Happened With the Women's Orchestra of Auschwitz

Looking at a Map of the Battle of Gallipoli Today

If you’re a student of history or just a curious traveler, looking at a map of the Battle of Gallipoli is an exercise in empathy. You start to see why things went wrong. You see the distances—so short on paper, so long under fire.

The peninsula is now a national park. The trenches are still there, though they're mostly shallow depressions covered in pine needles now.

Actionable Steps for History Enthusiasts

- Visit the Australian War Memorial (AWM) Digital Collection: They have high-resolution scans of original hand-drawn trench maps. Look for the ones with bloodstains or mud—it puts the "paper" in perspective.

- Compare 1915 vs. 2026: Use a 1915 trench map alongside a modern 3D topographic map. Notice how the "flat" areas on the old maps are actually treacherous slopes.

- Study the "Chunuk Bair" sector specifically: This was the highest point reached. Mapping this area shows the sheer verticality of the fight.

- Read "Gallipoli" by Peter Hart: He uses maps to explain why specific battalions vanished into the scrub. It’s a masterclass in how geography dictates destiny.

Maps are just paper until someone tries to walk them. At Gallipoli, the walking was the hardest part. The map said "victory was just over the next hill," but the hills never seemed to end.

To truly understand the campaign, stop looking for the lines and start looking at the contours. The closer the lines on the map, the steeper the hill. And at Gallipoli, those lines were almost touching. That tells you everything you need to know about why the campaign failed.

The next time you open a map of the Battle of Gallipoli, look at the distance between the Anzac landing and the heights of Sari Bair. It looks like a ten-minute walk. It took eight months, and they never quite made it.

End of Analysis. To get the most out of your research, download a high-resolution topographic map of the Gallipoli Peninsula and overlay it with the "General Staff Geographical Section" maps from 1915. This side-by-side comparison reveals the exact points where intelligence failed the soldiers on the ground.