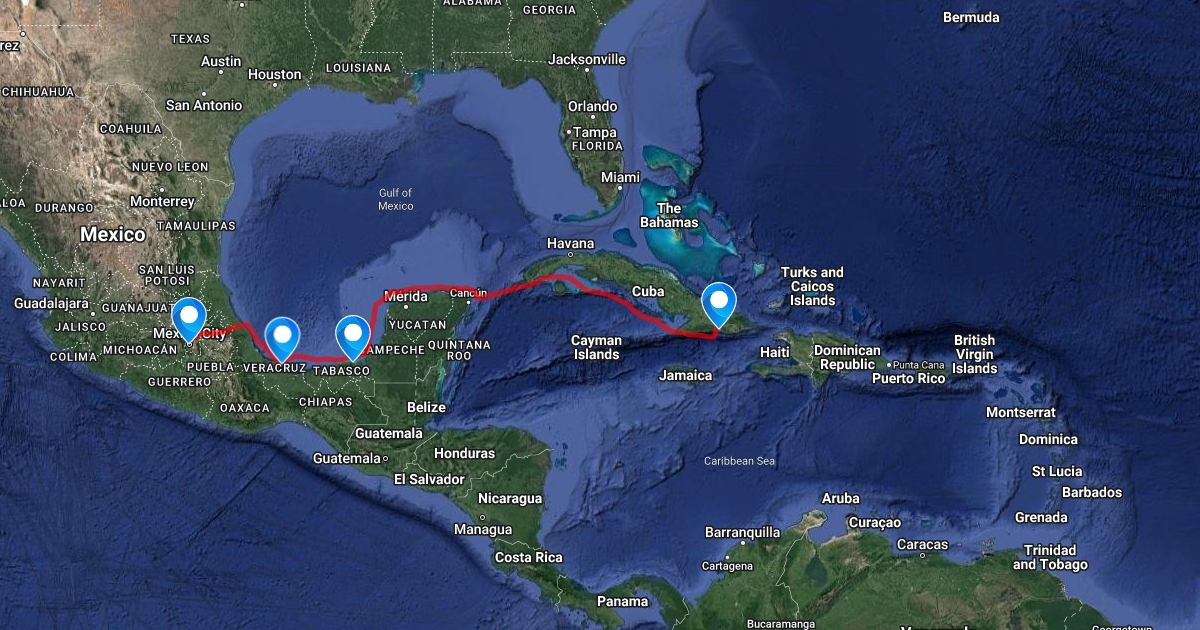

If you look at a modern map of Hernan Cortes journey, it looks like a clean, purposeful line cutting from the coast of Veracruz straight into the heart of the Aztec Empire. It’s easy to get that impression. Textbooks love a good arrow. But honestly? That "line" was a messy, desperate, and often confused scramble through some of the most vertical terrain on the planet.

You’ve probably seen the classic 1524 Nuremberg map—the one sent to King Charles V. It’s beautiful. It’s also kinda a lie. Or, at least, it’s a very specific version of the truth designed to make Cortes look like a strategic genius rather than a guy who was technically committing treason against the Governor of Cuba while trying not to get sacrificed in the mountains.

The Real Route from the Coast to Tenochtitlan

Cortes didn't just land and start marching. The journey began in February 1519 when he ditched Cuba with 11 ships. His first real stop on the mainland was the Grijalva River in Tabasco. This is where he picked up Malintzin (La Malinche), who basically became his human GPS and translator. Without her, any map of Hernan Cortes journey would have ended in a dead end within a week.

After founding Villa Rica de la Vera Cruz—mostly as a legal loophole to justify his expedition—the real climb started.

Imagine 500 Spaniards in steel armor, plus thousands of Totonac allies, trying to haul cannons through the Sierra Madre Oriental. They went through Jalapa and Xico. If you’ve ever driven these roads today, you know they’re steep. Back then? It was a nightmare of thin air and freezing rain. They weren't following a map; they were following rumors of gold and the very real advice of local enemies of the Aztecs.

💡 You might also like: Wingate by Wyndham Columbia: What Most People Get Wrong

Why Tlaxcala Changed Everything

On most maps, Tlaxcala is just a dot. In reality, it was the turning point. The Tlaxcalans didn't just open the gates; they fought the Spaniards tooth and nail first. Once they realized they couldn't beat the newcomers, they did something smarter: they joined them.

When you track the map of Hernan Cortes journey, the stop in Cholula is where things get dark. Depending on who you ask—Cortes or the indigenous accounts in the Florentine Codex—it was either a necessary pre-emptive strike or a brutal massacre. Either way, the route from Cholula led them to the "Paso de Cortés," the high mountain pass between the volcanoes Popocatépetl and Iztaccíhuatl.

Standing at nearly 12,000 feet, this is where the Spaniards first saw the Valley of Mexico. It wasn't just a valley; it was a massive lake system with a city that looked like it was floating.

The 1524 Nuremberg Map: A Masterpiece of Propaganda

The most famous visual we have of this era is the map published in Nuremberg in 1524. It’s the first European image of Tenochtitlan. It shows the city as a circular, orderly Venice-like marvel.

📖 Related: Finding Your Way: The Sky Harbor Airport Map Terminal 3 Breakdown

But look closer at the left side of that map. It includes a sketch of the Gulf of Mexico. It’s surprisingly accurate for the time, likely because it used indigenous charts that Montezuma actually gave to Cortes.

- The Island Myth: For years, this map led Europeans to believe the Yucatan was an island.

- The Habsburg Flag: Cortes had the map-maker plant the Spanish imperial flag right in the center. It wasn't just a map; it was a "Sold" sign.

- The Great Temple: The Templo Mayor is depicted in the center, but it’s drawn using European architectural styles—towers and battlements that wouldn't have looked like that in reality.

The Forgotten Disaster: The Journey to Honduras

Most people think the story ends with the fall of Tenochtitlan in 1521. It doesn't. If you want to see a truly insane map of Hernan Cortes journey, look at his 1524–1526 expedition to Honduras.

Cortes heard that one of his captains, Cristóbal de Olid, had gone rogue. Instead of sending a small party, Cortes decided to lead an army through the literal jungles of the Maya lowlands. It was a disaster. Bernal Díaz del Castillo, who was there, wrote that they almost starved to death. They spent weeks building bridges over swamps and hacking through vines.

This part of the map is a zigzag of misery. They crossed over 50 rivers. By the time Cortes reached Honduras, he was emaciated and his political power back in Mexico City was crumbling. It’s the part of the map that proves Cortes was often driven more by pride than by any logical sense of geography.

👉 See also: Why an Escape Room Stroudsburg PA Trip is the Best Way to Test Your Friendships

How to Trace the Route Today

If you're looking to actually see these places, the "Ruta de Cortés" is a legitimate travel itinerary in modern Mexico. You can start in the humid heat of Antigua (the second site of Veracruz) and work your way up to the cool, misty forests of Coatepec and Jalapa.

Key Stops for Your Itinerary:

- Quiahuiztlan: An amazing Totonac archaeological site overlooking the spot where Cortes anchored his ships.

- Cempoala: The "Place of Twenty Waters." This was the first major indigenous city Cortes entered.

- Tizatlan (Tlaxcala): You can still see the ruins of the altars where the alliance was likely forged.

- The Zócalo, Mexico City: This is where the Aztec Templo Mayor stood. The ruins are literally right next to the Cathedral.

The geography is the only thing that hasn't fundamentally changed. The mountains are still that steep. The volcanoes are still that imposing. When you look at a map of Hernan Cortes journey now, try to see the verticality of it. It wasn't a flat trek across a page. It was a brutal, high-altitude scramble that relied entirely on indigenous guides and political luck.

To get a deeper sense of the terrain, you should compare the 1524 Nuremberg woodcut with modern topographical maps of the Puebla-Tlaxcala valley. You'll see that while the lake is gone—drained over centuries—the mountain passes the Spaniards used are still the primary veins of travel through the region today. Look into the Relaciones Geográficas from the late 1500s; they provide some of the earliest localized maps drawn by indigenous artists that show how the landscape was perceived after the dust of the conquest had settled.