You’ve seen the photos. Those jagged, needle-like teeth splaying out from a mouth that looks like it was designed by a horror movie prop master. People call it the mako jaws of death, and honestly, it’s not hard to see why. When a Shortfin Mako (Isurus oxyrinchus) opens up, it’s not just a bite. It's a mechanical marvel of evolutionary engineering that has remained largely unchanged for millions of years.

But here is the thing.

Most of what we "know" about these sharks comes from grainy viral videos or tall tales from offshore fishermen. We see the speed. We see the teeth. We assume it’s a mindless killing machine. It isn't. It’s actually one of the most sophisticated predators on the planet, and those "jaws of death" are a highly specialized tool for one specific job: catching the fastest fish in the sea.

Why the Mako Jaws of Death Look So Terrifying

The first time you see a mako jaw up close—maybe at a bait shop or a museum—the thing that hits you is the protrusion. Unlike a Great White, which has broad, triangular, serrated teeth designed for sawing through blubber, the mako has what scientists call "villiform" or needle-like teeth.

They’re recurved. They point backward.

Why? Because makos eat squid and tuna. If you've ever tried to hold a wet bar of soap, you get the idea of what it's like to catch a tuna. They are pure muscle and slime. The mako’s teeth act like a series of gaff hooks. Once those teeth sink in, the prey isn't going anywhere. The harder the fish struggles, the deeper those hooks bite.

Basically, it's a trap.

The jaw itself isn't even fused to the cranium. This is the part that trips people up. When a mako strikes, it can actually "throw" its jaws forward. This is called palatoquadrate protrusion. It gives the shark an extra few inches of reach and allows it to create a vacuum effect, sucking the prey into that cage of teeth. It’s fast. Like, blink-and-you-miss-it fast.

👉 See also: How is gum made? The sticky truth about what you are actually chewing

The Physics of the Fastest Bite

We talk about the speed of the shark—clocked at over 45 mph in some bursts—but the speed of the jaw is just as nuts.

Studies by researchers like Dr. Cheryl Wilga have looked into the biomechanics of shark feeding. They found that the mako’s jaw muscles are dense and optimized for a "snap" closure. While a Bull Shark might have more raw crushing power—measured in Newtons that could flatten a car fender—the mako has the "jaws of death" because of its velocity.

Think of it like this:

- A Great White is a sledgehammer.

- A Mako is a switchblade.

The mako doesn't need to crush your bones. It needs to sever the spinal cord of a 60-pound Bluefin Tuna in a single pass. If it misses, or if it takes too long, that tuna is gone. The mako lives on a knife's edge of caloric expenditure. It burns so much energy swimming so fast (it's endothermic, meaning it’s warm-blooded, which is rare for sharks) that it has to be efficient. Every time those jaws open, it’s a high-stakes gamble.

Misconceptions and the "Jaws of Death" Moniker

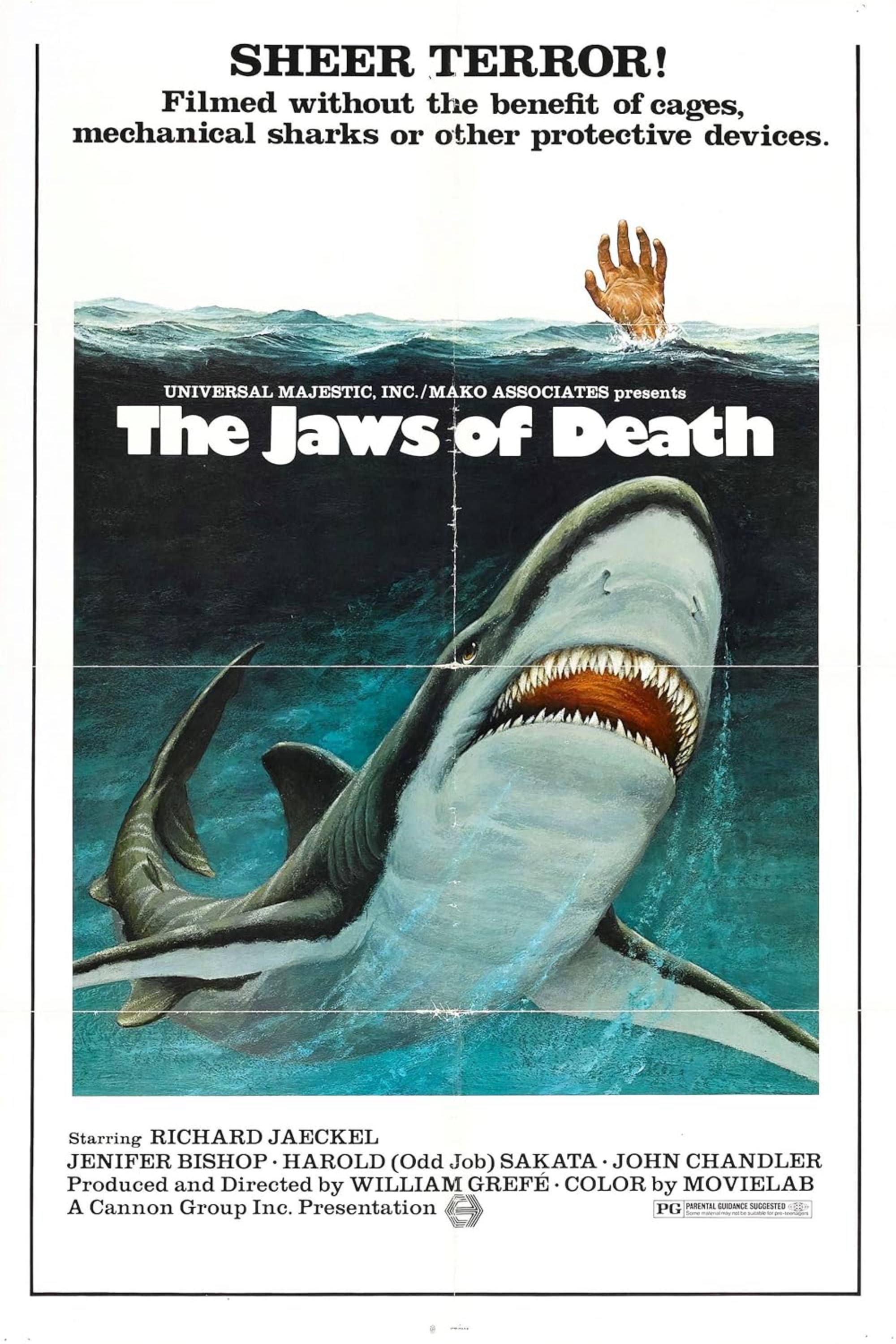

Let’s be real. The name "jaws of death" is largely a byproduct of the 1970s Jaws era and the subsequent sensationalism in sport fishing.

In the world of pelagic fishing, the Shortfin Mako is the "blue dynamite." When they get hooked, they jump. They can clear 20 feet of air easily. When they land in a boat—which happens more often than you’d think—those jaws become a very real hazard. There are dozens of documented cases of makos "attacking" boats or biting through gunwales.

But is it malice? No. It’s a fish out of water, literally, snapping at anything in its vicinity.

✨ Don't miss: Curtain Bangs on Fine Hair: Why Yours Probably Look Flat and How to Fix It

The danger is real, though. A mako's teeth are visible even when its mouth is closed. Because they are so long and numerous, they don't fit neatly inside the jawline like a Tiger shark’s. This gives them that permanent, haunting "grin" that makes for great (and terrifying) photography.

The Real Status of the Mako

While we fear their jaws, the irony is that these sharks are the ones in trouble.

The IUCN Red List currently lists the Shortfin Mako as Endangered. Their speed and those famous "jaws of death" haven't protected them from longline fishing and the demand for shark fin soup. Because they take years to reach sexual maturity—males around 8 years and females not until 18—they can't replenish their numbers fast enough to keep up with how many are being pulled out of the water.

In 2019, CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species) finally moved to protect them, but the black market for mako jaws remains a thing. You can still find dried mako jaws for sale online for hundreds of dollars. It’s a weird obsession we have: fearing the bite while simultaneously wanting to hang it on a wall.

What Happens During a Strike?

When a mako decides to eat, it doesn't just swim up and nibble. It approaches from below.

It uses its incredible vision and its ability to detect electromagnetic fields (through pores called the Ampullae of Lorenzini) to track the heartbeat of its prey. As it closes the gap, its eyes roll back into its head for protection. This is a crucial detail. At the moment of impact, the shark is essentially blind. It’s relying on pure instinct and the mechanical "click" of the jaw locking onto the target.

The teeth in the front do the grabbing. The teeth in the back are for shearing.

🔗 Read more: Bates Nut Farm Woods Valley Road Valley Center CA: Why Everyone Still Goes After 100 Years

If you look at a set of mako jaws, you’ll see rows of replacement teeth tucked behind the main ones. They’re like a conveyor belt. If a mako loses a tooth in a particularly violent struggle with a swordfish—a common rival—a new one moves forward in a matter of days. They go through thousands of teeth in a lifetime.

Human Encounters: Fact vs. Fiction

Are makos dangerous to humans?

Statistically, not really. They are pelagic, meaning they live in the open ocean, far from the beaches where most people swim. Most "mako jaws of death" stories come from divers or spearfishers. If you have a bleeding fish on the end of a spear, a mako will show up. And when it does, it’s like a lightning bolt.

They are curious. They "test bite" things to see if they’re edible. Unfortunately, a test bite from a mako can sever a femoral artery because of how those teeth are angled. You don't get "bitten" by a mako so much as you get "snagged."

Actionable Insights for Ocean Enthusiasts

If you're fascinated by the mako or happen to be a diver/fisherman, there are a few things to keep in mind regarding these apex predators. Understanding the mechanics of the jaw helps you respect the animal without falling for the "monster" narrative.

- Support the Ban on Mako Retention: Many countries, including the US (in the Atlantic), have implemented "no-possession" limits. If you catch one, it has to go back. Supporting these regulations is the only way to ensure the species survives.

- Identify the Teeth: If you find a shark tooth on a beach, look for the lack of serrations. If it’s smooth, sharp, and curved like a hook, you’re likely looking at a mako or its cousin, the Salmon shark.

- Avoid "Jaw" Souvenirs: Buying dried shark jaws creates a market for poaching. If you want to appreciate the anatomy, visit a reputable aquarium or look at high-resolution 3D scans provided by marine biology labs.

- Diving Safety: If you are lucky enough to see a mako while diving, keep your hands in. They are attracted to high-contrast colors and shiny objects (which look like fish scales).

The mako shark is a masterpiece of fluid dynamics. Those jaws aren't "death" in the way we think of it—they are life. They are the tool that allows this animal to exist in the harshest, most competitive environment on earth. We should be less worried about the bite and more worried about a world where that bite no longer exists.

To really understand the mako, look past the serrated imagery. Look at the efficiency. Look at the speed. The mako jaws of death are actually a testament to one of nature's most perfect designs.

Next Steps for Conservation Awareness:

Research the ICCAT (International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas) rulings on mako shark bycatch. Understanding how international law affects these animals is the first step in moving from a fan of the "jaws of death" to a protector of the species. Check out the Shark Trust or Oceana for real-time data on how mako populations are faring in your local waters. By shifting the narrative from fear to biology, we can help these "blue spirits" stay in the ocean where they belong.