Paper is flat. It’s stubborn. If you try to force a standard sheet of construction paper into a perfect sphere, it crinkles, protests, and eventually tears. But there is a way to trick geometry. Most people think you need specialized kits or weird plastics to build 3D structures, but honestly, making a dome out of construction paper is basically just a lesson in how triangles distribute weight. You’ve probably seen geodesic domes at science museums or maybe even at Epcot, and while those are massive engineering feats, the logic translates perfectly to the messy desk in your living room.

It’s all about the vertices.

The Secret Geometry Behind the Paper Dome

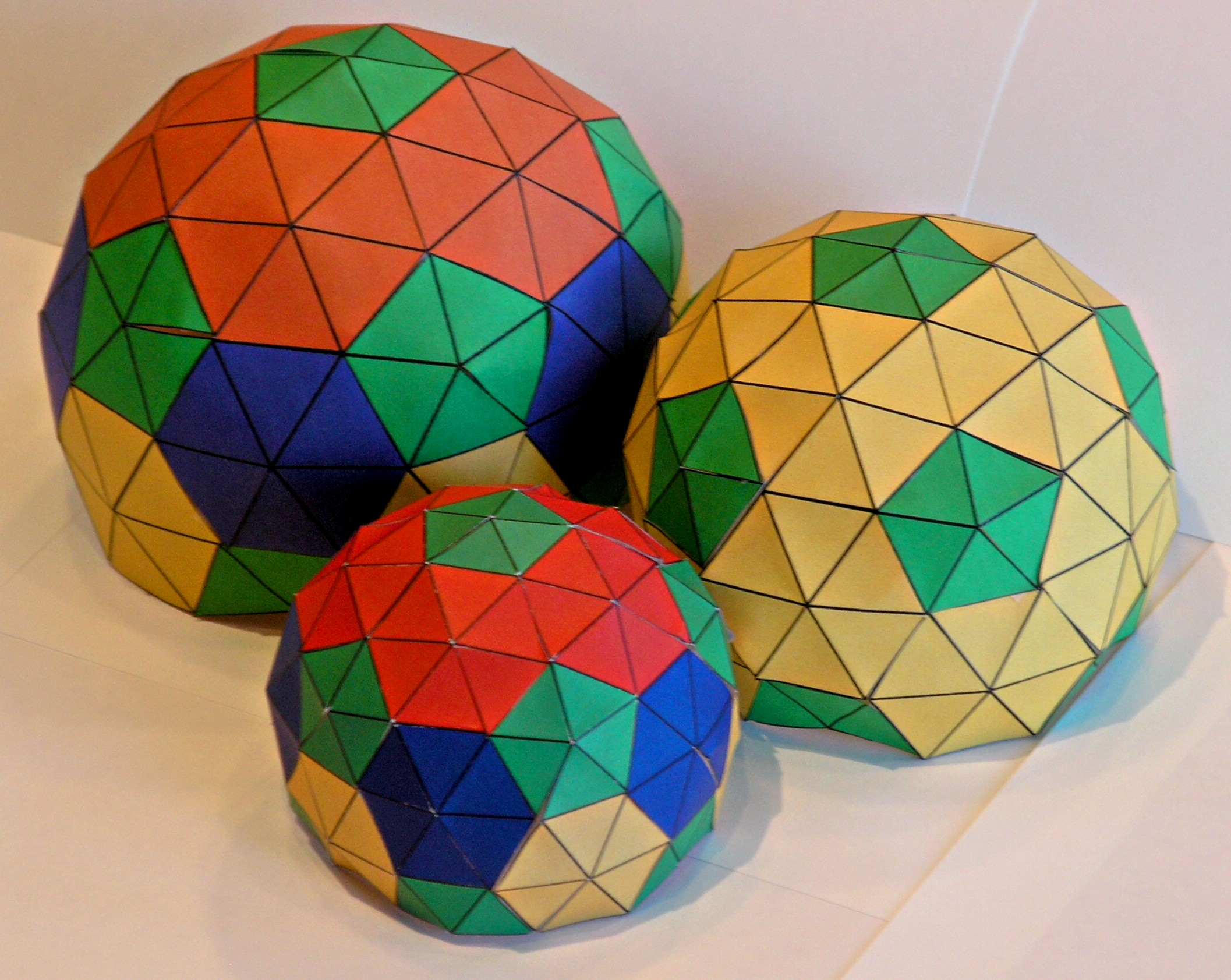

Before you grab the scissors, you have to understand why we don't just use one big circle of paper. A dome is a double-curved surface. Construction paper is "developable," meaning it only likes to curve in one direction at a time, like a cylinder. To get that iconic round shape, we have to use a geodesic design. This isn't just a fancy word; it refers to the shortest line between two points on a sphere. By using a series of interconnected triangles, we create a structure that approximates a curve while remaining incredibly rigid.

Buckminster Fuller, the guy who made the geodesic dome famous in the 20th century, realized that triangles are the only polygon that is inherently rigid. A square can collapse into a parallelogram. A triangle? It stays a triangle until the material itself snaps. When you’re making a dome out of construction paper, you’re essentially recreating the work of engineers who built the Montreal Biosphere.

You'll need two different lengths of paper strips. Let's call them Type A and Type B. If you make them all the same length, you'll end up with a flat hexagon pattern that won't curve downward. The slight variation in length—usually about a 10% to 12% difference—is what forces the paper to "bow" into a 3D hemisphere.

What You’ll Actually Need

Don't overcomplicate the tool kit. You need heavy-weight construction paper because the thin, cheap stuff from the dollar store lacks the structural integrity to hold its own weight once the dome gets larger than a grapefruit.

Grab a good pair of shears. You’ll also want a ruler with millimeter markings, a pencil, and either a high-quality glue stick or—if you’re impatient like me—a stapler. A stapler is faster, but it adds weight. If you want a "clean" look for a school project or a desk model, go with double-sided tape or a quick-dry tacky glue. Avoid school glue (the white liquid stuff). It saturates the fibers, makes the paper soggy, and takes forever to dry, which leads to your dome collapsing under its own damp weight before you even finish the third row.

📖 Related: Popeyes Louisiana Kitchen Menu: Why You’re Probably Ordering Wrong

How to Calculate Your Strut Lengths

This is where most people quit. They try to wing it. Don't wing it.

To build a standard 2V (two-frequency) geodesic dome, you need 35 "long" struts and 30 "short" struts. Let’s say you want a dome that’s about a foot wide. Your "A" struts (the long ones) should be roughly 16 centimeters. Your "B" struts (the short ones) should be about 14 centimeters.

- Cut 35 strips of blue paper (Type A) at 16cm.

- Cut 30 strips of red paper (Type B) at 14cm.

- Make sure each strip is about 2cm wide.

Why different colors? Trust me. Once you have 65 strips of paper scattered on your floor, you will lose track of which is which. Color-coding is the only way to stay sane.

The Assembly Process: Starting from the Top

Start at the "North Pole" of your dome. You’re going to create a pentagon using five of your shorter "B" struts. Join them at a central point. It’ll look like a star. This is the crown.

Once that star is formed, you’ll connect the outer points of the star using your longer "A" struts. This creates five triangles pointing outward. Now, here is the trick: the next layer requires you to alternate. You’ll be forming a mix of hexagons and pentagons.

It starts feeling floppy. That's normal. Construction paper is flexible, and until the base ring is closed, the whole thing will feel like a wet noodle. Don't panic. Just keep following the geometric pattern: pentagons are surrounded by hexagons.

👉 See also: 100 Biggest Cities in the US: Why the Map You Know is Wrong

Why Construction Paper is Actually Better Than Cardboard

You might think cardboard would be stronger. It is, but it’s also a nightmare to fold at the precise angles needed for a dome's vertices. Construction paper has this "sweet spot" of flexibility and tensile strength. When you overlap the ends of the strips and staple them, you're creating a reinforced joint.

In real-world architecture, these joints are called hubs. In your paper version, the hub is just a messy pile of overlapping paper. But even in this simple form, the physics are the same. The weight of the paper is distributed down through the triangles to the surface of the table. You could probably rest a light book on top of a well-made paper dome, and it wouldn't even flinch.

Common Pitfalls (And How to Fix Them)

The most common mistake when making a dome out of construction paper is "creep." Creep happens when your measurements are just a tiny bit off—maybe a millimeter here or there. By the time you get to the fifth row of triangles, those millimeters add up. Suddenly, the last piece doesn't fit.

If this happens, don't throw it away. Just trim the last few struts to fit. This isn't NASA; it's paper. The dome is forgiving because the material can stretch and bend slightly to accommodate human error.

Another issue is humidity. If you live in a swampy climate, construction paper absorbs moisture from the air. It gets soft. If your dome starts sagging after a few days, it’s not your fault—it’s the air. You can prevent this by lightly misting the finished structure with a clear acrylic spray or even hairspray. It seals the fibers and keeps the "stiff" feeling.

Advanced Mods: Adding a "Skin"

A skeleton dome is cool, but a "skinned" dome looks like a real building. If you want to cover the triangles, don't try to wrap the whole thing in one piece of paper. It won't work. You have to cut individual triangles out of tissue paper or thinner construction paper and glue them onto the frame.

✨ Don't miss: Cooper City FL Zip Codes: What Moving Here Is Actually Like

This adds a surprising amount of strength. It’s similar to how a drumhead works—the tension of the "skin" pulls the frame together and makes it significantly more rigid.

The Physics of the "Paper Hub"

If you really want to geek out, look at the vertices. When you join five or six strips of paper at one point, you are creating a focal point for stress. Professional dome builders use steel hubs or 3D-printed connectors. For us, a single staple or a dot of glue does the job because the loads are so small.

However, notice how the paper curves slightly between the joints. This is called "pre-stressing." In a weird way, the slight imperfections in your hand-cut strips actually help the dome stay up. The tension keeps the structure "pushed out" against gravity.

Where to Take This Project Next

Once you've mastered the basic 2V dome, you can try a 3V dome. It requires way more pieces—around 165 struts—but the result is much smoother and more spherical. It looks less like a Dungeons & Dragons die and more like a real architectural dome.

You can also experiment with scale. Try making a dome out of full-sized 12-inch strips. It'll be huge. It might even be big enough for a cat to sit inside. Just remember that as you increase the size, the weight of the paper increases faster than its strength. You might need to double-layer the paper strips to keep them from buckling under the weight of the upper tiers.

Actionable Next Steps

- Audit your paper supply: Ensure you have at least two distinct colors of heavy construction paper to avoid measurement confusion.

- Calculate your ratio: Use a 1.0 to 0.88 ratio for your A and B struts (e.g., 10cm for A and 8.8cm for B).

- Pre-punch your holes: If you're using brass fasteners instead of staples, use a hole punch on all your strips at once to ensure the distances between the holes are identical.

- Start small: Build a "proof of concept" dome with 5cm struts first to understand how the pentagons and hexagons lock together before wasting a whole pack of paper.

- Clear a dedicated space: You need a flat surface where the dome can sit undisturbed; trying to move a half-finished paper dome is a recipe for a structural collapse.