If you walked up to the Magna Carta text original today, you probably couldn't read a single word of it. Not because it’s faded—though some copies are definitely showing their age—but because it isn't even written in English. It’s in heavily abbreviated medieval Latin. Squinting at those 63 clauses scrawled on sheepskin parchment, you’d see a wall of text that looks more like a legal receipt than a revolutionary cry for freedom.

It was a failure. Honestly, it's weird we celebrate it at all.

When King John met those fed-up barons at Runnymede in June 1215, he wasn't trying to build a democracy. He was trying to stop a civil war he was losing. He signed it, hated it, and then got the Pope to annul the whole thing barely ten weeks later. Yet, here we are, eight centuries deep, still talking about it.

The Raw Reality of the Magna Carta Text Original

The first thing to understand is that there isn't just one "original." Back in 1215, there were no printing presses. Scribes in the Royal Chancery had to hand-write multiple copies to be dispatched to sheriffs and bishops across England. We call these "engrossments." Out of maybe dozens sent out, only four survive today. Two are at the British Library, one is at Salisbury Cathedral, and the last is at Lincoln Cathedral.

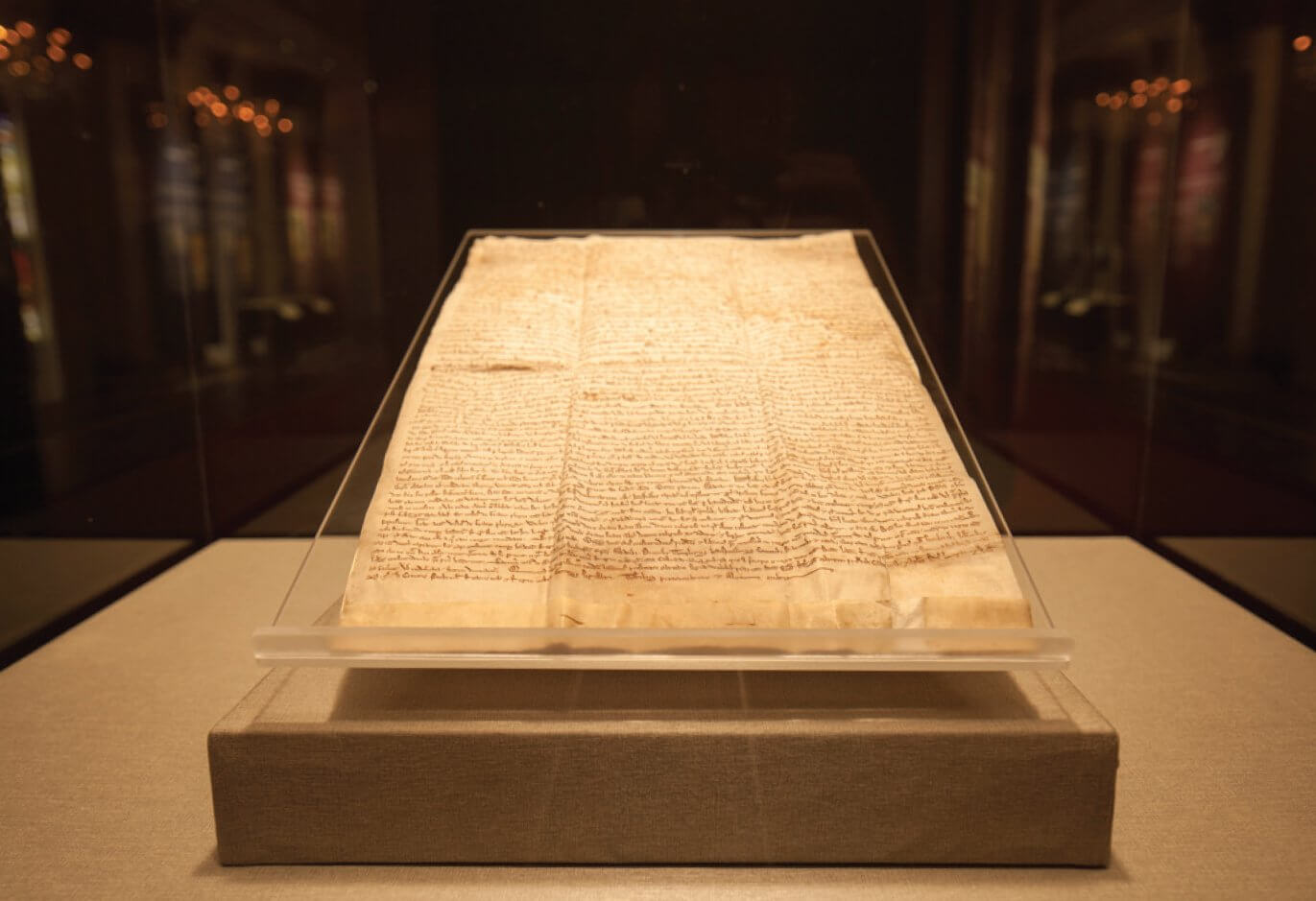

The physical nature of the Magna Carta text original is gritty. It’s written on vellum, which is basically dried calfskin or sheepskin. It’s tough. It’s oily. It’s meant to last forever, which is lucky for us.

It’s Not a Constitution

Most people think the 1215 text is a soaring declaration of human rights. It isn’t. Most of it is incredibly boring. We’re talking about very specific, very annoyed complaints about fish weirs in the Thames, standardizing the widths of dyed cloth, and how much a baron’s heir should pay to inherit land. It's a "Great Charter" mostly because it's long, not because it was initially "great" in the moral sense.

✨ Don't miss: Why Every Tornado Warning MN Now Live Alert Demands Your Immediate Attention

The text is a mess of feudal technicalities. Clause 33, for instance, demands the removal of all fish-traps from the Medway. Why? Because they messed up navigation for boats. It sounds trivial, but for a 13th-century merchant, that was a bigger deal than "abstract liberty."

Why Clause 39 Changes Everything

Among the talk of debts to Jewish moneylenders and forest boundaries, there is a spark. Clause 39 is the heavy hitter. If you look at the Magna Carta text original, it’s nestled right in the middle, not even highlighted.

It says: "No free man shall be seized or imprisoned... except by the lawful judgment of his equals or by the law of the land."

That’s it. That’s the seed of the right to a jury trial. It’s the origin of "due process." Before this, the King could basically throw you in a hole because he didn't like your face or wanted your castle. Now, he had to follow a rulebook. Even if John intended to ignore it, the idea was out. You can't un-ring that bell.

The phrasing "law of the land" (per legem terre) became the bedrock for the US Constitution centuries later. It’s the bridge between medieval power struggles and modern civil rights.

🔗 Read more: Brian Walshe Trial Date: What Really Happened with the Verdict

The Language Barrier

The Latin used in the 1215 manuscript is incredibly dense. Scribes used a shorthand system called sigla to save space on expensive parchment. Words are chopped off. "And" becomes a little symbol. "Queen" or "King" might just be a letter with a flourish.

If you were to look at a high-resolution scan of the Cotton MS Augustus ii.106 (one of the British Library copies), it looks like a barcode of ink. It wasn't meant to be read by the public. It was meant to be read by lawyers and officials who knew the jargon. It was a contract. A messy, desperate, last-minute contract.

Myths That Need to Die

- King John didn't sign it. He didn't even have a pen. He used the Great Seal. He pressed a wax disk into the parchment to authorize it. If you see a painting of John holding a quill, the artist was lying to you.

- It wasn't about "the people." In 1215, "free men" were a tiny minority. Most people in England were unfree serfs or villeins. The Magna Carta text original did almost nothing for them. It was a deal for the 1%, by the 1%.

- It didn't work. Within months, the barons were back at war with the King. John died of dysentery a year later, and the charter was reissued by his son, Henry III, in 1216, 1217, and 1225. The version that actually made it into English law is usually the 1297 version.

The Evolution of the Manuscript

When we talk about the Magna Carta text original, we have to acknowledge how it changed. The 1215 version had 63 clauses. By the time it became "official" law under Edward I in 1297, it had been trimmed down to about 37.

Some of the weirdest stuff got cut.

There was a whole section (Clause 61) called the "Security Clause." It basically said that if the King broke the rules, a committee of 25 barons could legally wage war on him and seize his castles until he fixed it. Imagine that in a modern constitution. "If the President messes up, 25 guys are allowed to take over the White House until he apologizes." No wonder John got the Pope to scrap it. It made him a puppet.

💡 You might also like: How Old is CHRR? What People Get Wrong About the Ohio State Research Giant

Where to See the Real Deal

If you want to see the 1215 Magna Carta text original, you have a few options, but don't expect a pristine document.

- The British Library: They have two. One was badly damaged in a fire in 1731. It’s a shriveled, blackened piece of skin, but they used multi-spectral imaging in 2014 to finally read the text again. It's haunting.

- Salisbury Cathedral: This is arguably the best-preserved copy. It’s been there basically since it was written.

- Lincoln Cathedral: This one traveled. It was even in the US during World War II for safekeeping.

Actionable Insights: How to Study the Text

You don't need a degree in paleography to understand this document. If you're looking to actually engage with the Magna Carta text original, start here:

- Use Multi-Spectral Scans: Don't just look at photos. The British Library offers deep-zoom scans where you can see the grain of the parchment. It helps you realize this was a physical, hand-made object.

- Read the 1215 vs. 1297 Comparisons: Most "Magna Carta" quotes you see online are actually from the later versions. Check the 1215 original to see the raw, angrier version of the clauses.

- Focus on the "Except" Clauses: The power of the document isn't in what it gives, but what it restricts. Look for the words nisi (unless) and praeter (except). Those are the legal loopholes that defined English liberty.

- Visit the Sites: If you’re in the UK, go to Runnymede. There’s no original text there—just a meadow—but standing in the damp grass helps you understand why the barons picked a spot where the King’s heavy cavalry would get stuck in the mud. It was a tactical meeting, not a picnic.

The Magna Carta text original isn't just a museum piece. It’s a reminder that rights aren't usually granted by "nice" leaders. They are clawed back by people who are tired of being taxed and bullied. It started as a failed peace treaty and ended up as the DNA of modern freedom. Not bad for a piece of old sheepskin.

To dive deeper into the specific legal translations, compare the 1215 Latin manuscript directly against the 17th-century English translations by Sir Edward Coke, who was the one responsible for reviving the charter's relevance during the struggle against the Stuart kings. Understanding his "re-interpretation" is key to seeing how a medieval document became a tool for 17th-century revolution.