Movies from the late 2000s have a specific kind of energy. It’s that glossy, slightly frantic, Lifetime-original-movie vibe that feels like a time capsule of our collective insecurities. When Lying to Be Perfect—often known by the book title it’s based on, The Cinderella Pact—hit screens in 2010, it tapped into something visceral. It wasn't just about weight loss. It was about the messy, often toxic way we navigate female friendship, body image, and the digital lies we tell to feel seen.

You know the plot. Or you think you do.

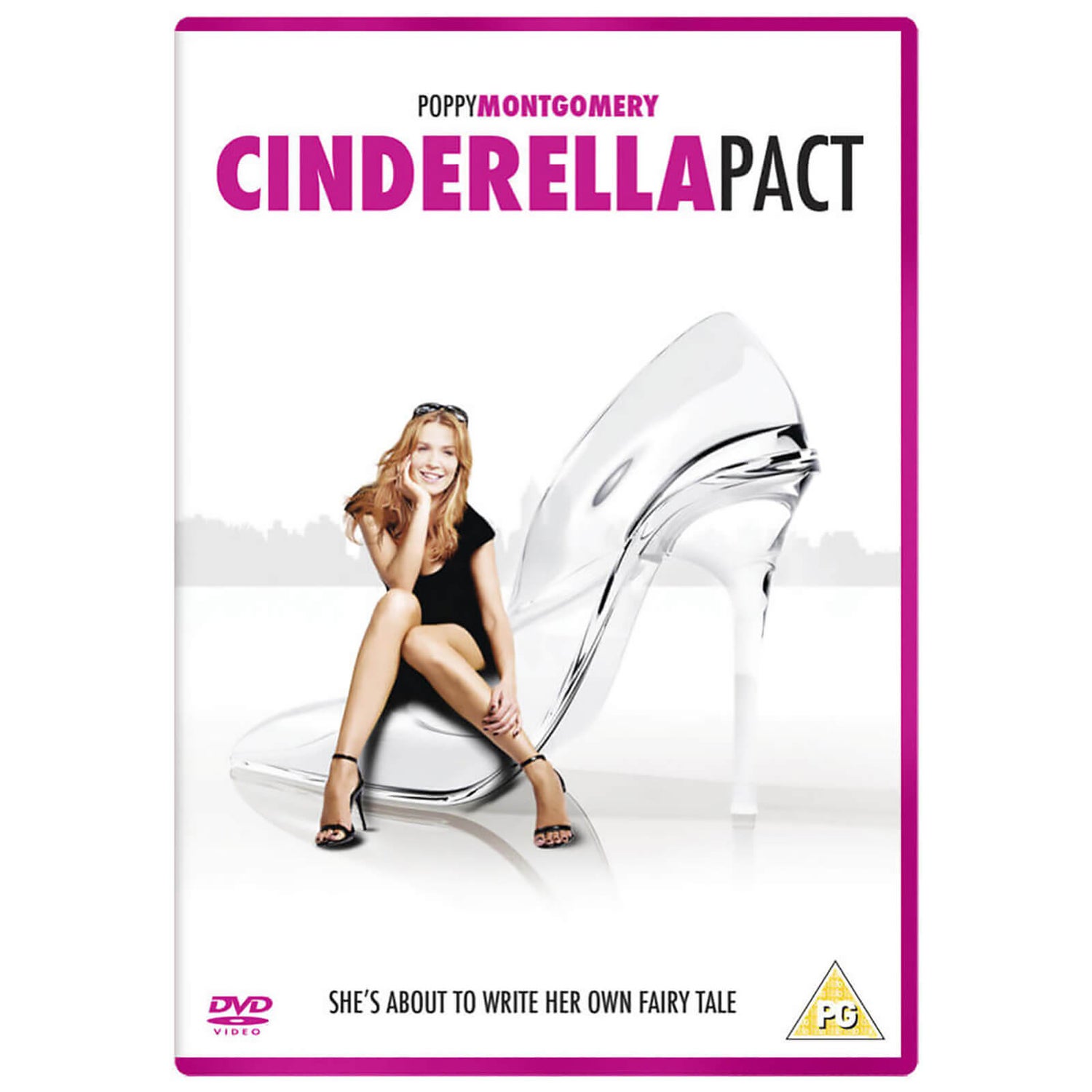

Poppy Montgomery plays Nola Devlin, an editor at a fashion magazine who hides behind a persona named "Belinda Apple." While Nola is plus-sized and feels invisible in the cutthroat world of New York publishing, Belinda is the thin, glamorous, "perfect" advice columnist everyone admires. It’s a classic secret-identity trope. But then things get weird. Nola and her two best friends, inspired by Belinda's (Nola's own!) advice, make the "Cinderella Pact." They decide to lose weight and transform their lives to match the societal ideal.

Honestly, looking back at it now, the movie is a fever dream of pre-body-positivity culture. It’s fascinating, cringey, and deeply revealing about how we viewed "perfection" fifteen years ago.

The Weight of the Secret Identity

Nola Devlin is a relatable protagonist, mostly because she's exhausted. Balancing a high-pressure job while maintaining a secret life as a famous columnist is a lot. But the core of Lying to Be Perfect isn't just the logistical lie; it’s the emotional one. Nola believes her actual self—the one who enjoys food and doesn't fit into a size 2—is fundamentally unworthy of the life she’s earned.

The movie explores a specific kind of "imposter syndrome" that's literal.

The 2000s were obsessed with the "makeover." Think The Devil Wears Prada or Miss Congeniality. However, Lying to Be Perfect adds a layer of deception that feels closer to modern catfishing. Nola isn't just changing her clothes; she’s manipulating how the world perceives her talent by attaching it to a "socially acceptable" face. It’s a cynical take on the industry, yet it’s played with the lighthearted tone of a rom-com. That contrast is where the movie gets its staying power. It makes you wonder: would people have listened to Nola if they knew what she looked like from the start? Probably not. That's the uncomfortable truth the film handles with varying degrees of success.

👉 See also: Album Hopes and Fears: Why We Obsess Over Music That Doesn't Exist Yet

Why the Cinderella Pact Matters in the Age of Filters

We don't really use the term "pact" much anymore. Now, we have "challenges" or "glow-ups." But the Cinderella Pact—the agreement between Nola, Deb, and Nancy to lose weight and change their lives—is the precursor to the curated lives we see on Instagram and TikTok today.

The pact was meant to be empowering. It was three friends supporting each other. Yet, it was rooted in the idea that they were "broken" to begin with.

The Psychology of Group Transformation

When friends decide to change together, it creates a unique social pressure. In the movie, the pact acts as a catalyst for honesty, but also for immense guilt. If one person slips up, does the whole thing crumble? The film shows the highs of the weight loss journey, but it also touches on the isolation Nola feels because she’s still lying about being Belinda. She’s winning at the pact, but she’s losing her soul in the process.

Most people who watch Lying to Be Perfect today might find the "before and after" tropes a bit dated. We’ve moved toward body neutrality. But the desire to be someone else? That’s eternal. Nola’s struggle is the 2010 version of using a "Bold Glamour" filter. She’s just doing it with a pen name and a column instead of pixels.

Behind the Scenes: From Book to Screen

The movie is based on the novel The Cinderella Pact by Sarah Strohmeyer. If you've read the book, you know the movie takes some liberties. Strohmeyer’s writing often leans into the "chick lit" genre of the era, which was characterized by witty, self-deprecating humor and a sharp look at social hierarchies.

Poppy Montgomery was a huge get for Lifetime at the time. She was coming off the success of Without a Trace and brought a level of "realness" to Nola. She had to play the character with a mix of vulnerability and sharp-edged ambition. The supporting cast, including Adam Kaufman as the love interest, rounds out the typical rom-com ensemble, but the chemistry between the three female leads is what carries the emotional weight.

✨ Don't miss: The Name of This Band Is Talking Heads: Why This Live Album Still Beats the Studio Records

Real-World Reception

Critics at the time were split. Some saw it as a harmless, feel-good movie about self-acceptance. Others criticized it for reinforcing the idea that you have to lose weight to get the guy and the promotion. It’s a valid critique. Even though the "lesson" is about being yourself, the narrative spends 90 minutes focusing on the physical transformation as the key to happiness.

The Fashion Magazine Mythos

Lying to Be Perfect leans heavily into the "Fashion Magazine" trope. You know the one: everyone is mean, everyone drinks green juice, and the offices look like a museum of minimalist furniture.

Nola’s workplace is a character in itself. It represents the "Perfection" she’s trying to lie her way into. In these movies, fashion isn't just clothes; it’s armor. For Nola, her Belinda Apple persona is the ultimate armor. It’s impenetrable. But armor is heavy. By the time she reaches her breaking point, the movie shifts from a comedy of errors into a genuine drama about the cost of keeping up appearances.

It's actually kinda wild how much these movies influenced our perception of the publishing world. Real editors will tell you it’s mostly spreadsheets and coffee, but Lying to Be Perfect wants us to believe it’s all about the "reveal."

Addressing the "Lie" in Lying to Be Perfect

Let's talk about the ethics. Nola lies to her boss. She lies to her best friends. She lies to the man she loves.

Is she a hero? Or is she a bit of a villain?

🔗 Read more: Wrong Address: Why This Nigerian Drama Is Still Sparking Conversations

The movie argues she’s a victim of a shallow society. If the world wasn't so judgmental, she wouldn't have to lie. There's truth there. But the movie also explores how lying becomes an addiction. Once Nola starts seeing the benefits of being "Belinda," she finds it harder and harder to let go. She likes the power. She likes the way people look at her. It’s a cautionary tale about how easy it is to lose your identity when you start performing for others.

What We Get Wrong About the Ending

People often remember the ending as a simple "she got the guy" moment. But the actual takeaway is more about the dissolution of the "Cinderella Pact."

The pact was a crutch.

By the end, the characters realize that the weight loss wasn't the thing that changed their lives—it was the confidence they gained by finally being honest with themselves. Nola has to burn down her "Belinda" life to save her "Nola" life. It’s a professional suicide mission that somehow turns into a personal victory. It’s unrealistic, sure. It’s a movie. But the sentiment—that you can't build a real life on a fake foundation—is the most "human" part of the script.

Actionable Insights: Lessons from the Cinderella Pact

If you’re revisiting this movie or watching it for the first time, there are some pretty solid takeaways you can apply to your own life, minus the dramatic 2000s makeover montage.

- Audit Your "Personas": We all have them. The "LinkedIn" version of you, the "Instagram" version. Are they so far removed from the real you that they’re causing stress? If you’re exhausted from the act, it’s time to bridge the gap.

- Re-evaluate Your "Pacts": Group goals are great, but make sure they’re based on growth, not shame. If a "pact" with friends makes you feel guilty for being human, it’s a bad pact.

- The Power of Radical Honesty: Nola’s biggest break came when she stopped lying. In the real world, vulnerability is often a more effective "networking" tool than perfection. People connect with flaws, not polished facades.

- Challenge the Beauty Standard: Recognize that the "perfection" Nola was chasing in 2010 was a moving target. Beauty standards change every decade. Chasing them is like running a race with no finish line.

The film is a relic, but its heart is in the right place. It reminds us that even if we manage to lie our way into a "perfect" life, we won't be there to enjoy it—only our persona will. To actually live your life, you have to show up as yourself. Flaws, food cravings, and all.