You've probably spent at least one evening hunched over a laptop, staring at a tax return and wondering why the system has to be so incredibly complicated. It feels like a maze of brackets, deductions, and "gotcha" moments. But there is a concept in economics that tosses all that out the window. It's called a lump sum tax.

Basically, it's the simplest tax imaginable.

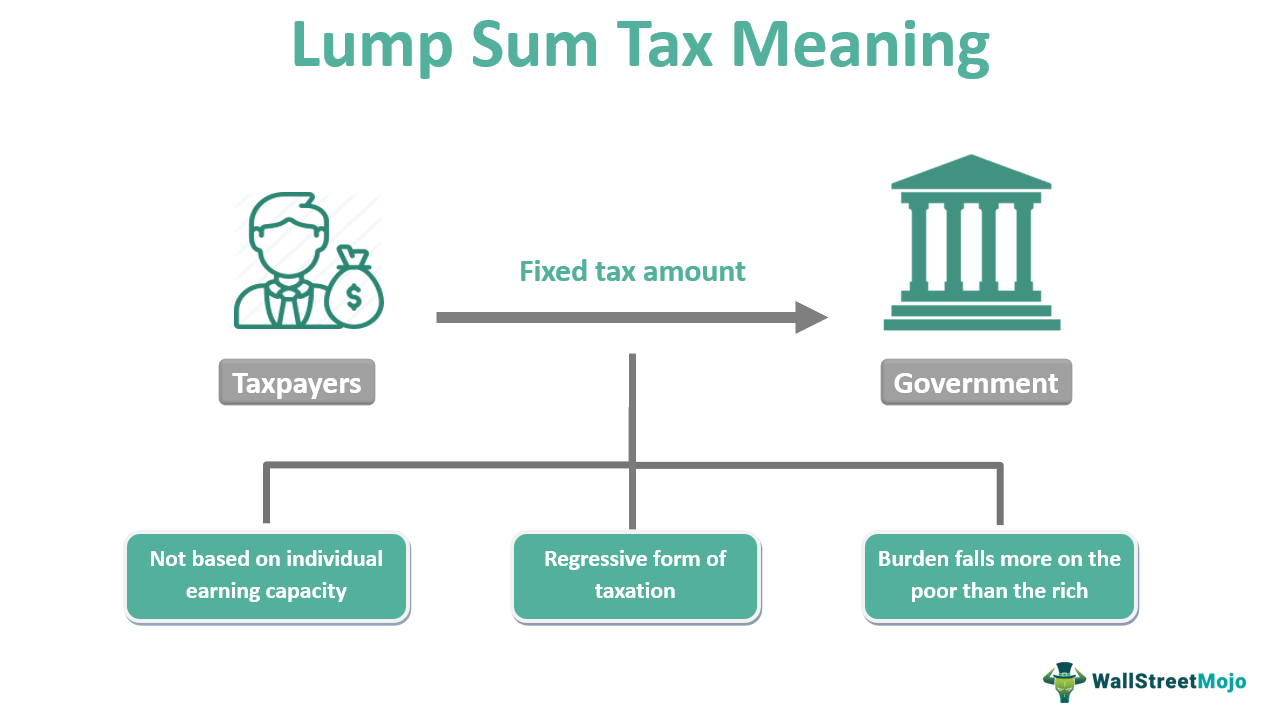

Instead of the government taking a percentage of your paycheck or adding a few cents to your coffee purchase, they just send you a bill for a fixed amount. Everyone pays the same. No math. No loopholes. Just a flat fee for existing.

While that might sound like a nightmare for your bank account if you're struggling to make ends meet, economists generally view it as the "gold standard" of efficiency. Why? Because it doesn't change your behavior. Most taxes—like income tax—actually discourage people from working more or investing. A lump sum tax doesn't care how much you earn. It just exists.

The Theory of the "Perfect" Tax

In the world of welfare economics, the lump sum tax is famous for being non-distortionary.

Think about it this way. If the government raises the tax on cigarettes, you might quit smoking. If they raise the tax on income, you might decide that working an extra ten hours of overtime isn't worth it because the "take-home" pay is too small. These are called deadweight losses. They represent economic activity that just... vanishes because of the tax structure.

A lump sum tax avoids this entirely.

Economists like Nicholas Gregory Mankiw or the late Paul Samuelson have often pointed out that this type of tax satisfies the "First Fundamental Theorem of Welfare Economics." It allows the market to reach a Pareto efficient outcome. Basically, since the tax is fixed, your marginal incentive to earn more money remains exactly the same as it was before the tax.

You still get to keep every extra dollar you earn.

But here is the catch. Real-world implementation is a total mess. While it's efficient on paper, it's often viewed as "regressive" in the extreme. If a billionaire and a barista both owe $5,000, the barista is going to have a much harder time buying groceries than the billionaire will.

When History Tried (and Failed) to Use It

We don't have to guess how people feel about this. We've seen it play out.

The most famous—or perhaps infamous—example is the Community Charge, better known as the "Poll Tax," introduced by Margaret Thatcher in the United Kingdom in 1989 (Scotland) and 1990 (England and Wales).

It was a classic lump sum tax.

🔗 Read more: H1B Visa Fees Increase: Why Your Next Hire Might Cost $100,000 More

Instead of local taxes being based on the value of your home (rates), every adult was charged a flat fee to fund local services. The logic was that since everyone uses the streetlights and the parks, everyone should pay the same for them.

The backlash was immediate. And violent.

The "Poll Tax Riots" in Trafalgar Square saw hundreds of thousands of protesters clashing with police. People hated it because it ignored the ability to pay. It was one of the primary reasons Thatcher eventually lost her grip on power. It's a stark reminder that what works in a textbook can fail spectacularly in the streets.

Honesty, it was a political suicide mission.

Why It’s Still a "Ghost" in Modern Policy

Even though "pure" lump sum taxes are rare, elements of them show up in modern life.

Consider a flat annual vehicle registration fee. It doesn't matter if you drive a beat-up 2005 sedan or a brand-new Ferrari; in many jurisdictions, you pay the same $100 or $200 a year to register that car. That's a lump sum tax.

Television licenses in countries like Ireland or the UK (though changing now) are another example. If you have a TV, you pay the fee. Period.

- It's predictable for the government.

- It's cheap to administer because you don't need to audit someone's income.

- It provides a steady stream of revenue.

But these are usually "small" fees. When the numbers get big enough to fund a whole government, the "fairness" argument starts to crumble.

The Efficiency vs. Equity Trade-off

This is the big battle in economics.

On one side, you have Efficiency. A lump sum tax is the winner here. No distortions. No wasted effort by accountants trying to find loopholes. Just pure revenue.

On the other side, you have Equity. This is where the lump sum tax fails. Most modern societies believe in "Vertical Equity," which is the idea that those with a greater ability to pay should contribute more.

If you look at the work of Thomas Piketty, he argues that wealth inequality is already so baked into the system that taxes need to be more progressive, not less. A lump sum tax would do the opposite—it would likely widen the gap between the rich and the poor because the tax takes a much higher percentage of a lower-income person's total wealth.

💡 You might also like: GeoVax Labs Inc Stock: What Most People Get Wrong

It’s kinda fascinating how a policy can be both "perfect" and "impossible" at the same time.

Could a Lump Sum Tax Ever Work Today?

There is a weird twist in this story.

Some people argue that Universal Basic Income (UBI) is actually a "negative" lump sum tax. Instead of everyone paying $500 to the government, the government gives everyone $500.

It has the same efficiency benefits.

Because everyone gets the same amount regardless of how much they work, it doesn't discourage you from taking a job. It's the mirror image of the lump sum tax theory. This is why you sometimes see libertarian economists supporting UBI; they like the lack of market distortion.

However, a "positive" lump sum tax—where you pay the government—remains a political third rail. No one is running for office on a platform of "Everyone pays $10,000, no matter what."

It would be a short campaign.

Real-world Complexity

In reality, governments use a mix.

Most countries rely on income taxes (distortionary but progressive) and sales taxes (somewhat distortionary but easy to collect). Lump sum elements are usually tucked away in the form of "user fees" or "licenses."

The legal definition of a tax versus a fee is often where the lump sum debate lives in the courts. If a city charges every household $50 for "trash collection" regardless of how much trash they produce, is it a tax? Or is it a service fee?

Courts have wrestled with this for decades.

In the United States, the Head Tax (a form of lump sum tax) is actually restricted by the Constitution. Article I, Section 9, requires that "direct taxes" be apportioned among the states based on population. This makes a national lump sum tax on individuals legally incredibly difficult to pull off without a specific amendment.

📖 Related: General Electric Stock Price Forecast: Why the New GE is a Different Beast

What Most People Get Wrong

People often confuse a Flat Tax with a Lump Sum Tax. They aren't the same.

A Flat Tax means everyone pays the same percentage (e.g., 15% of income). A Lump Sum Tax means everyone pays the same dollar amount (e.g., $5,000).

The difference is huge.

Under a flat tax, the person earning $1,000,000 pays way more than the person earning $30,000. Under a lump sum tax, they pay exactly the same. The lump sum tax is much "stricter" in its application and, ironically, much more efficient in a purely mathematical sense.

It’s the ultimate "no-frills" approach to government finance.

But humans aren't variables in an equation. We care about fairness. We care about the "pain" of the tax. And the pain of a $1,000 tax bill is not the same for everyone.

Moving Forward: Actionable Insights

If you’re looking at how tax structures affect your own life or business, understanding these principles helps you spot where "hidden" lump sum taxes are eating your budget.

- Identify Fixed Costs: Look for "flat" fees in your business or personal life—registration fees, flat-rate licenses, or mandatory subscriptions. These are essentially lump sum taxes. Because they don't change based on your income, they are most "expensive" when your revenue is low.

- Evaluate Marginal Incentives: When you’re deciding whether to take on extra work, calculate your "marginal tax rate." This is the tax on your next dollar. A lump sum tax has a marginal rate of zero. An income tax might have a marginal rate of 25% or higher. If your marginal rate is too high, it might actually make sense to work less.

- Watch Local Policy: Local governments are more likely to implement lump sum-style fees (like flat utility surcharges) than state or federal governments. Keep an eye on city council meetings where "fee structures" are discussed, as these often bypass the traditional tax debate.

- Understand Regressive Impacts: If you are a business owner setting prices, remember that a flat "per customer" fee is harder on your lower-income clients than a percentage-based fee. This is the "equity" lesson of the lump sum tax applied to your own business model.

Taxes are rarely just about money. They are about values.

The lump sum tax represents the value of pure efficiency. Our current progressive tax systems represent the value of social equity. The tension between the two is why your tax return is probably still going to be a headache next year.

It’s just the price we pay for a system that tries to be fair instead of just being "efficient."

Honestly, even if a lump sum tax would save you hours of paperwork, you'd probably still join the protest if the bill was the same for you as it was for a tech mogul. Economics can explain the "how," but it can't always solve the "should."

That part is up to us.

Next Steps for Implementation

To get a better handle on how different tax structures impact your financial health, start by calculating your Effective Tax Rate versus your Marginal Tax Rate. Your effective rate is the total percentage of your income that goes to taxes, while your marginal rate tells you how much the government takes from your last hour of work. Understanding this gap will show you exactly how "distortionary" the current system is for your specific situation.