Finding the lowest common ancestor in binary tree structures feels like one of those whiteboard problems designed specifically to make engineers sweat. It shouldn't be that hard, right? You have two nodes. You want to find the lowest node in the tree that has both of them as descendants. Simple. But then you start coding, and suddenly you're drowning in null pointer exceptions or realizing your recursive approach just blew up the stack on a skewed tree.

It's a classic for a reason. Whether you’re working on autocomplete features, file systems, or genealogy software, the logic of the LCA is a fundamental building block.

What exactly are we looking for?

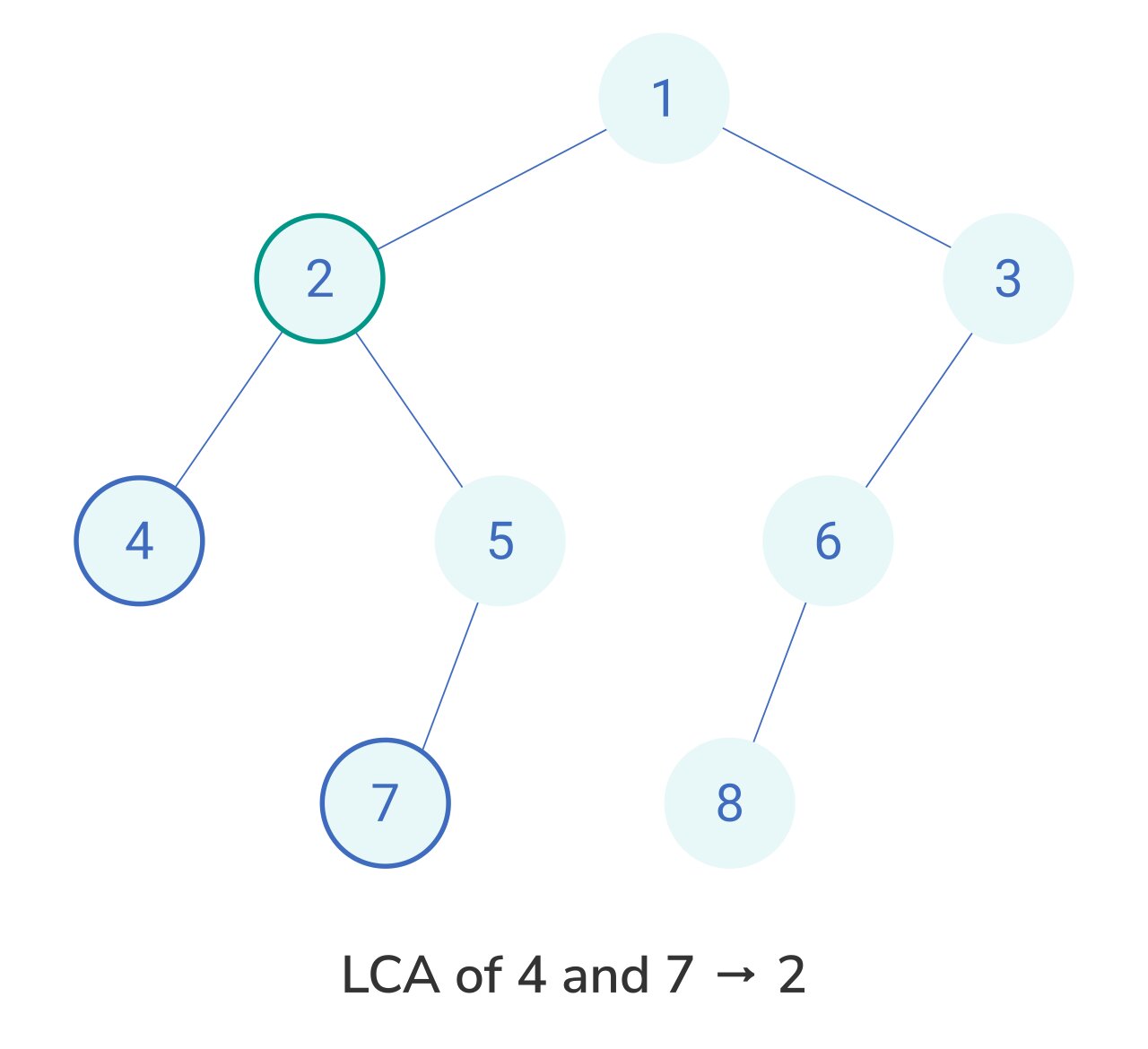

Let’s be real. When we talk about the lowest common ancestor in binary tree setups, we aren’t just looking for "any" ancestor. We want the one furthest from the root. If you have a family tree and you’re looking for the LCA of you and your sibling, it’s your parent. Your grandparent is also a common ancestor, but they aren't the lowest.

In a formal sense, the LCA of two nodes $p$ and $q$ is the lowest node $T$ that has both $p$ and $q$ as descendants—and yes, we follow the standard definition where a node can be a descendant of itself. This little detail trips up a lot of people. If node $p$ is the direct parent of node $q$, then $p$ is actually the LCA.

👉 See also: I Just Realized My Facebook Account Is Hacked: The Immediate Steps You Need To Take Right Now

The recursive "Eureka" moment

Most people start with recursion. It’s intuitive. You look left, you look right, and you hope the answer bubbles up.

Think about it this way. If you are sitting at a node, you ask your left child: "Hey, do you see $p$ or $q$?" Then you ask your right child the same thing. If the left child says "I found one" and the right child says "I found the other," then congratulations, you are the LCA. You’re the bridge between those two branches.

But what if only one side finds something? That means both $p$ and $q$ are likely located down that specific path, and the first one encountered is the LCA. If neither side finds anything? You return null.

Here is where it gets tricky. If you're using Python or Java, a simple recursive function looks clean, but it hides a lot of complexity. You’re essentially performing a post-order traversal. You go all the way to the leaves and work your way back up.

Why your first solution might be slow

If you’re doing this once, $O(n)$ time complexity is fine. You visit every node, no big deal. But imagine you’re Facebook or Google. You aren't finding the lowest common ancestor in binary tree one time. You're doing it millions of times on a graph that barely fits in memory.

This is where the distinction between "one-off" queries and "preprocessing" comes in. If the tree is static—meaning it isn't changing—you can preprocess the tree to answer LCA queries in $O(1)$ or $O(\log n)$ time.

✨ Don't miss: The NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090 Founders Edition Graphics Card: Why It Still Rules the High-End Market

Tarjan's off-line LCA algorithm is a beast for this. It uses a Disjoint Set Union (DSU) to find ancestors in almost constant time. It’s "off-line" because you need to know all your queries ahead of time. It’s less like a conversation and more like a pre-planned roadmap.

The Binary Lifting trick

If you want to sound like the smartest person in the room during a system design interview, mention binary lifting.

Instead of climbing up the tree one parent at a time—which is slow if the tree is deep—you jump. You store the $2^0$-th ancestor (the parent), the $2^1$-th ancestor (the grandparent), the $2^2$-th ancestor, and so on.

It’s basically binary search but for tree heights. To find the LCA, you first bring both nodes to the same depth. Then, you start taking the biggest jumps possible without overshooting the LCA. It turns a painful $O(n)$ climb into a sleek $O(\log n)$ sprint.

When trees aren't "normal"

The lowest common ancestor in binary tree problem changes completely if the tree is a Binary Search Tree (BST). In a BST, you have order. Everything to the left is smaller; everything to the right is larger.

You don't need fancy recursion or DSU for a BST. You just start at the root. If both nodes are smaller than the root, go left. If both are larger, go right. The moment you find a node where one target is smaller and the other is larger, you’ve found your LCA. It’s elegant. It’s fast. Honestly, it’s a relief compared to general binary trees.

Real-world messy details

In the real world, trees aren't always in memory. They might be distributed across servers. Or, more commonly, your "nodes" might not have parent pointers.

If you don't have parent pointers, you're forced to start from the root. If you do have parent pointers, you can treat the problem like finding the intersection of two linked lists. You trace the path from $p$ to the root and the path from $q$ to the root. Where the paths meet? That’s your LCA.

There's also the issue of "missing" nodes. A common trap in coding challenges is when $p$ or $q$ isn't actually in the tree. A standard recursive function might mistakenly return $p$ if it finds $p$ and never even looks for $q$. You have to do a secondary check to ensure both nodes exist, or your results are basically junk.

Practical Steps to Master LCA

If you're looking to actually implement this or use it in a project, don't just copy-paste a snippet. Follow these steps to make sure your implementation is actually robust:

📖 Related: تنزيل فيديو تيك توك: كل ما تحتاج معرفته عن الحفظ بدون علامة مائية

- Identify the Tree Type: Is it a BST? If yes, use the value-comparison method. It's much faster and easier to debug.

- Check for Parent Pointers: If your data structure includes a

node.parentreference, don't use recursion. Use a hash set to store the path of one node and then iterate up from the second node until you hit a match. - Handle the "Self-Ancestor" Case: Always clarify if a node can be its own ancestor. In 99% of computer science applications, the answer is yes.

- Account for Scale: If you are querying the same tree repeatedly, look into the Euler Tour technique. By flattening the tree into an array using a Depth First Search (DFS), you can turn the LCA problem into a Range Minimum Query (RMQ) problem.

- Verify Existence: Before returning a result, ensure both nodes actually reside in the tree to avoid false positives in your search logic.

The lowest common ancestor in binary tree isn't just a puzzle; it's a lesson in trade-offs between memory, time, and code complexity. Whether you go with a simple recursive DFS or a complex Sparse Table for $O(1)$ queries, the "best" way always depends on your specific constraints.