Logic is cold. Love is messy. When Max Shulman published his short story "Love is a Fallacy" in 1951, he probably didn't realize he was creating a permanent syllabus for every Intro to Logic student in the country. It’s a hilarious, slightly cynical look at a law student named Dobie Gillis who tries to "train" a woman to be his ideal wife by teaching her how to think. He teaches her the love is a fallacy fallacies—a list of logic errors—only to have her use those very same tools to reject him. It’s poetic justice. But beyond the irony, Shulman actually laid out a pretty solid foundation for how we mess up our arguments in real life.

Most people think logic is for debates or math. Wrong. Logic is for when your partner says "you always do this" or when a politician promises a "simple solution" to a global crisis. We use these patterns every day. Sometimes we use them to win; mostly we use them because we're lazy thinkers.

The Origin of the Love is a Fallacy Fallacies

Shulman’s protagonist, Dobie, is the definition of "too smart for his own good." He wants a girl named Polly Espy, but he views her as a project. To him, she's beautiful but "logically challenged." He strikes a deal with his roommate, Petey Bellows, to trade a raccoon coat for the chance to date Polly. It’s a transaction. That’s his first mistake.

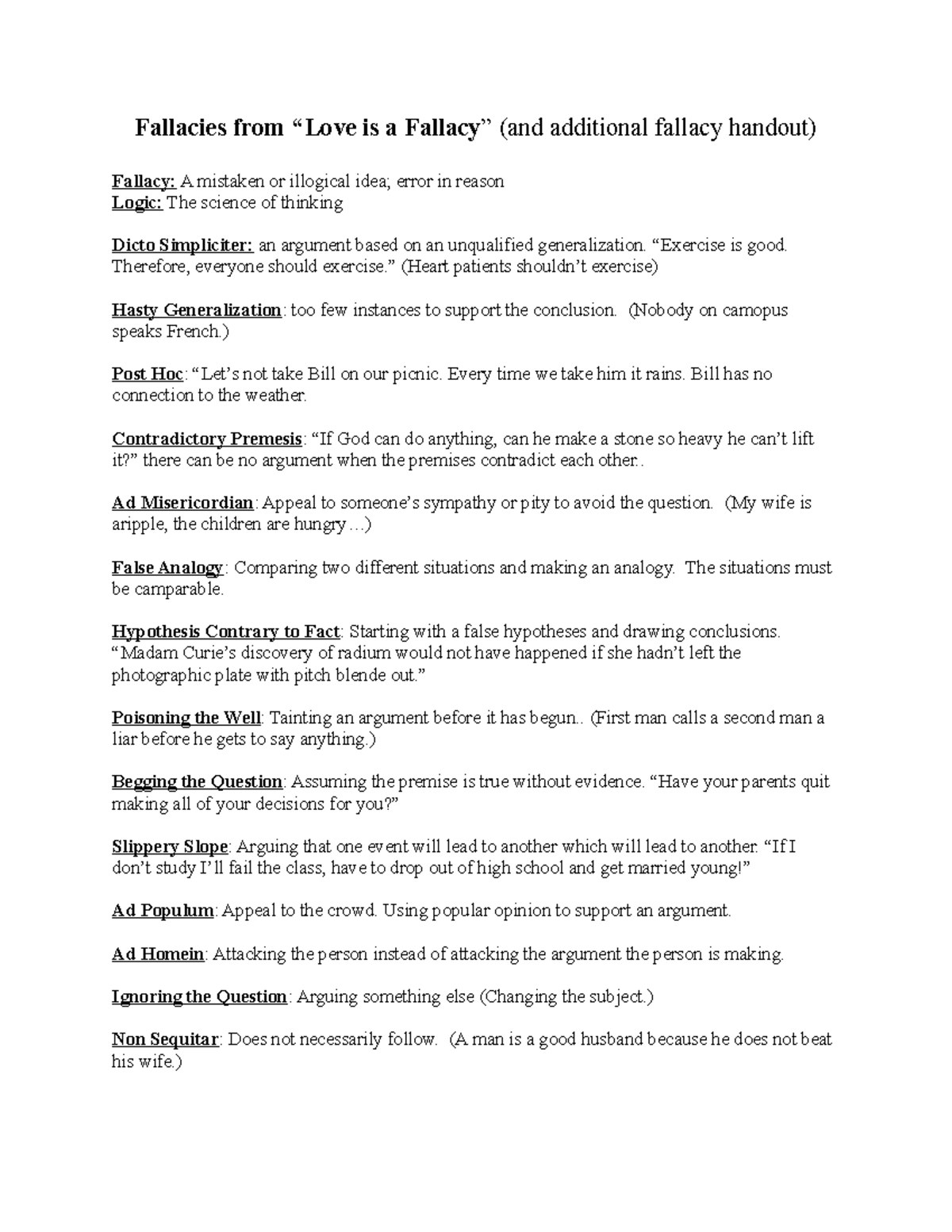

His second mistake is assuming that once Polly learns the love is a fallacy fallacies, she will naturally choose him over the "un-logical" Petey. The story walks us through eight specific logical errors. These aren't just academic terms; they are the gears that grind in our brains when we’re trying to justify something we already want to believe.

Dicto Simpliciter (The Unqualified Generalization)

Dobie starts with Dicto Simpliciter. This happens when you apply a general rule to a specific case where the rule doesn't actually fit.

Imagine saying "Exercise is good for everyone." Sounds fine, right? But if you say that to someone with a severe heart condition who was just told by a doctor to stay in bed, you’re committing Dicto Simpliciter. The rule is too broad. It ignores the exceptions. In the story, Dobie tries to explain that because exercise is good, everyone should exercise. Polly, in her initial "simple" state, just nods along. We do this all the time in modern wellness culture. We take a study about 20 college students in a lab and tell the whole world they need to drink three gallons of lemon water a day.

Hasty Generalization

This is the cousin of Dicto Simpliciter, but it works in the opposite direction. Instead of applying a broad rule to a small case, you take one or two small cases and invent a broad rule.

"I dated two guys from New Jersey and they were both loud, so everyone from New Jersey is loud."

That’s a Hasty Generalization. It’s the backbone of most stereotypes. Shulman’s character points out that you can’t speak French just because you know one person who speaks French and lives in Paris. It seems obvious when written down, but look at your social media feed. One bad experience with a brand becomes "This company is a total scam!" One flight delay becomes "This airline is the worst in history!"

The Slippery Slope of Emotional Logic

Logic isn't just about facts; it's about how those facts connect. Or don't.

✨ Don't miss: Why Every Bride Is Considering a Green Color Wedding Dress Right Now

One of the most famous love is a fallacy fallacies mentioned is Post Hoc Ergo Propter Hoc. This is Latin for "after this, therefore because of this." It is the king of superstitions.

If I wear my lucky socks and my team wins, did the socks cause the win? My brain says yes. Science says no.

Dobie explains to Polly that just because Bill followed Harry doesn't mean Harry caused Bill to appear. We see this in economics constantly. A new mayor takes office, and three months later the crime rate drops. The mayor takes credit. But maybe the drop started two years ago? Maybe it rained for three weeks straight and nobody wanted to go outside? Correlation is not causation, but our brains are wired to find patterns even where they don't exist. We crave a "why."

Ad Misericordiam (The Appeal to Pity)

This one hits close to home for anyone who has ever tried to get out of a speeding ticket. Instead of arguing the facts—"I wasn't speeding"—you argue the feelings—"But officer, I'm having a really bad day and my cat is sick and I just lost my job."

In the story, Dobie uses the example of a man applying for a job. When asked about his qualifications, he talks about his wife, his kids, and his lack of money. He’s not qualified, but he wants you to feel bad for him.

Honestly, this is the most common "fallacy" in modern relationships. We substitute our needs and hurts for actual logic. We think that being the one who suffers the most gives us the right to win the argument. It doesn’t. It just makes the other person feel guilty.

Why Polly Espy Won (and Why We Usually Lose)

The twist in Shulman’s story is the most important part of the love is a fallacy fallacies discussion. After weeks of lessons, Dobie asks Polly to go steady. He expects a logical "yes" because he has "improved" her.

Instead, she rejects him.

When he asks why, she uses his own lessons against him. He tries to use an Ad Misericordiam (telling her how much he's sacrificed for her), and she calls him out on it. He tries to use False Analogy, and she shuts it down.

The ultimate irony? She chooses Petey Bellows.

Why? Because Petey has a raccoon coat.

Dobie is horrified. He thinks she's being illogical. But from Polly’s perspective, she found a different "logic." She wanted the coat. Petey had the coat. Therefore, Petey was the better choice.

The Limit of Pure Reason

This brings up a massive point that experts like Daniel Kahneman (author of Thinking, Fast and Slow) have talked about for decades. Humans are not "rational actors." We are "rationalizing actors." We make emotional decisions and then use logic to justify them after the fact.

Shulman was mocking the idea that you can control people with "correct" thinking. You can't. Logic is a tool, not a remote control for human behavior. If you go into a relationship expecting it to work like a syllogism, you're going to end up alone with a textbook.

Real World Fallacies: More Than Just a Story

If you want to see the love is a fallacy fallacies in the wild, you don't have to look far.

Poisoning the Well is a huge one. This is when you discredit someone before they even speak. "Don't listen to him, he’s a known liar." Even if the guy is telling the truth this time, you've already "poisoned the well" so nobody believes him. We see this in every political debate. We see it in office politics. We see it when we tell a friend, "Don't date her, I heard she's crazy."

Then there's Hypothesis Contrary to Fact. This is the "what if" game. "If I hadn't met you, I'd be a millionaire by now." You can't prove that. You can't start with a premise that didn't happen and then draw a "fact" from it. It's all speculation. It’s a waste of mental energy, yet we spend half our lives living in these alternate timelines.

How to Actually Use This Knowledge

Knowing the names of these fallacies won't make you popular at parties. Trust me. If you start shouting "Dicto Simpliciter!" during a Thanksgiving dinner, you're not going to get the last piece of pie. You're going to get asked to leave.

The real value of understanding the love is a fallacy fallacies is internal. It’s about checking yourself.

- Stop the Generalizations: Next time you say "Everyone is..." or "Always...", catch yourself. It’s almost never true.

- Check the Sequence: Just because Event B happened after Event B doesn't mean A caused B. Give it a minute. Look for other variables.

- Watch the Pity Party: If you find yourself explaining why you're a victim instead of why you're right, you've lost the argument already.

- Recognize the Raccoon Coat: People have their own motivations. They might not be your motivations. That doesn't make them "illogical"; it just makes them different.

Actionable Steps for Better Thinking

Don't just read about these; apply them to your own habits. Logic is a muscle.

- Audit your last argument. Think about a fight you had with a friend or partner. Did you use an Ad Misericordiam? Did they use a Hasty Generalization? Identifying it after the fact helps you spot it in real-time next time.

- Read the News with a Fallacy Map. Pick a persuasive op-ed. Try to find at least three fallacies. Most political writing is built on Poisoning the Well and False Analogy. Once you see the strings, the puppet show isn't as convincing.

- Practice Steel-manning. This is the opposite of a "Straw Man" fallacy (where you misrepresent someone's argument to make it easy to attack). Instead, try to build the strongest possible version of your opponent's argument. If you can beat the strongest version, then you've actually won.

Dobie Gillis lost the girl because he thought he was the smartest person in the room. He forgot that logic is a map, but the territory is human emotion. If you want to navigate the world better, learn the fallacies so you can avoid them—not so you can use them to feel superior to everyone else.

Logic should be a window, not a weapon. Use it to see more clearly, not to cut people down. Because at the end of the day, someone might just walk away with the raccoon coat while you’re still trying to define the terms of the debate.