You’ve heard the voice. That gravelly, sandpaper-and-honey rasp that could only belong to one man. When Louis Armstrong sings the first few notes of Go Down Moses, something shifts in the room. It isn’t just jazz. It isn't just a "nice" Sunday morning spiritual. It feels like a heavyweight boxer stepping into the ring, but instead of gloves, he’s carrying a trumpet and a lifetime of survival.

Honestly, people often pigeonhole Louis as the "What a Wonderful World" guy—the smiling entertainer with the handkerchief. But "Pops" had teeth.

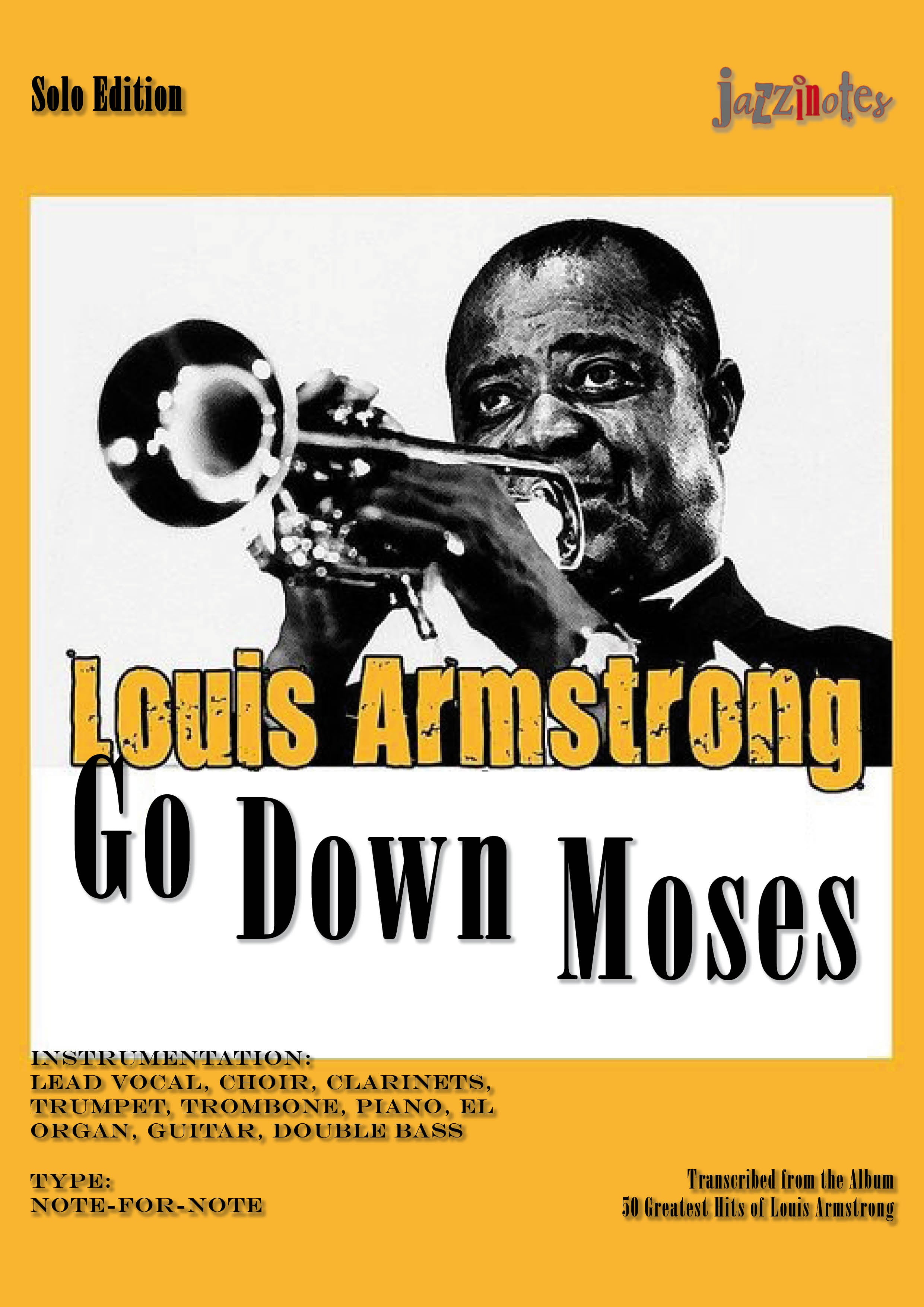

Recorded in February 1958 for the album Louis and the Good Book, his rendition of Louis Armstrong Go Down Moses is a masterclass in controlled power. It was a tense time in America. The Civil Rights movement was boiling over. Just months before this session, Louis had famously blasted President Eisenhower for being "two-faced" during the Little Rock Nine integration crisis. He was angry. He was hurt. And you can hear every bit of that defiance in this track.

The Sound of the 1958 Sessions

The album Louis and the Good Book wasn't some casual side project. It was a homecoming. Louis grew up in the churches and streets of New Orleans, where spirituals were the air people breathed. For this specific recording, he brought in the Sy Oliver Choir.

Sy Oliver was a genius arranger, basically the guy who helped define the "swing" era. He didn't over-orchestrate it. He kept the focus on the call-and-response, a tradition that goes back to the fields where enslaved people used music as a code and a lifeline.

Who was in the room?

- Louis Armstrong: Vocals and Trumpet (obviously).

- Trummy Young: Trombone (his long-time collaborator).

- Hank D’Amico: Clarinet (who replaced Edmond Hall for this specific date).

- Billy Kyle: Piano.

- Mort Herbert: Bass.

- Barrett Deems: Drums.

They recorded it on February 7, 1958, in New York City. The vibe is heavy but swinging. When the choir answers Louis's command of "Let my people go," it doesn't sound like a suggestion. It sounds like a demand.

More Than a Bible Story

The song itself is ancient—well, as ancient as American spirituals get. It dates back to the mid-19th century. Enslaved people in the South identified deeply with the Israelites in Egypt. Pharaoh wasn't just a guy in a history book; he was the plantation owner.

✨ Don't miss: Why the Book Club Cast Still Makes Us Want a Glass of Chardonnay

When Louis sings it, he bridges the gap between the 1850s and the 1950s.

"When Israel was in Egypt's land... Let my people go!"

There's a specific moment at the end of the song that always gets me. Louis isn't singing anymore. He picks up his trumpet. He hits this high-pitched burst—an exclamation point. It’s like he’s saying, "I’ve said my piece, now listen to the truth."

Kinda amazing when you think about it. Here was a man who was technically a "global ambassador" for the U.S. State Department, yet he was using his platform to record songs about liberation while his own country was still segregated. He knew exactly what he was doing.

Why This Version Ranks Above the Rest

There are hundreds of versions of "Go Down Moses." Paul Robeson did a legendary, deep-bass version that is haunting and operatic. The Golden Gate Quartet did it with tight, rhythmic harmonies.

But Louis? Louis makes it human.

He doesn't sing it like a preacher behind a pulpit. He sings it like a man who has walked those miles. His phrasing is slightly behind the beat, giving it a weary, "how much longer?" feel. Then, when the tempo picks up, the resilience kicks in. It’s that New Orleans "second line" energy—the idea that even in grief, we move forward.

Surprising Details You Might Not Know

- Code Song: Harriet Tubman allegedly used "Go Down Moses" as a signal to fugitive slaves. Louis knew the history. He wasn't just singing a "hit."

- The "Good Book" Context: This album followed Louis and the Angels (1957). While the "Angels" album was a bit more whimsical, The Good Book was far more grounded and serious.

- The Trumpet Absence: Notice how little he actually plays the trumpet on this track? He saves it. He lets the voice do the heavy lifting, making the eventual trumpet solo feel like a revelation.

The Legacy of Louis Armstrong Go Down Moses

A lot of people today think Louis was "safe." They think he wasn't radical enough compared to Miles Davis or Max Roach. But listen to this recording again.

Listen to the grit.

By taking a Negro Spiritual and putting it on a major label (Decca) with high-end production, he was forcing the "Pharaohs" of the music industry to acknowledge the roots of the music they were selling. He was reclaiming the narrative.

How to Appreciate It Today

- Listen for the Choir: Notice how Sy Oliver uses the choir not just as background noise, but as the voice of the "people" Louis is trying to lead.

- The Final Note: Wait for that last trumpet blast. It’s the sound of a man who refuses to be silenced.

- Contextualize: Play it alongside his 1957 interview about Little Rock. The connection is undeniable.

If you want to understand the soul of American music, you have to spend time with this track. It isn't just a relic of the past; it’s a living document of the struggle for freedom.

To truly experience the weight of this performance, find a high-quality vinyl pressing or a lossless digital version of Louis and the Good Book. Listen to the way the bass interacts with the choir's low hum. It’s not just a song; it’s a prayer for justice that hasn't lost an ounce of its relevance. Go find the 1958 mono recording if you can—it has a punch that the later stereo "enhanced" versions sometimes lose.

💡 You might also like: Session 9 Where to Watch: How to Stream the Cult Horror Classic Right Now

Next Steps

- Listen to the full album: Louis and the Good Book features other essentials like "Nobody Knows the Trouble I've Seen" and "Swing Low, Sweet Chariot."

- Compare versions: Contrast Louis’s 1958 version with Paul Robeson’s 1930s recording to see how the song evolved from a somber spiritual to a swinging protest anthem.

- Read the history: Look into Ricky Riccardi’s work at the Louis Armstrong House Museum for more on Armstrong’s complicated relationship with the Civil Rights movement.