Growing up in Butcher Hollow meant something specific. It wasn't just about being poor; it was about a particular kind of isolation that breeds a very specific kind of grit. When people hear the phrase daughter of a coal miner, they usually think of the song first. Maybe they think of the 1980 movie where Sissy Spacek managed to capture that Appalachian twang without making it a caricature. But for Loretta Lynn, this wasn't a branding exercise or a clever hook for a Nashville demo. It was a literal, soot-stained reality that defined how she saw the world until the day she died in 2022.

She was born in 1932. Times were lean.

Her father, Melvin "Pappy" Webb, worked the mines in Van Lear, Kentucky. If you've never looked into what coal mining was like in the 1930s and 40s, it’s a nightmare of respiratory issues and constant, low-grade fear. The family lived in a cabin where the wallpaper was literally made of old Sears Roebuck catalogs and newspapers. This wasn't for decoration. It was for insulation. Without those layers of paper, the wind would whistle straight through the gaps in the wood. When we talk about the daughter of a coal miner, we are talking about a woman who grew up seeing her father come home with eyes lined in black dust that no amount of scrubbing could ever fully remove.

The Cultural Weight of Being a Daughter of a Coal Miner

There is a massive misconception that the song "Coal Miner's Daughter" was an instant, calculated hit designed to pull at the heartstrings of working-class America. Honestly? Loretta didn't even think it was her best work when she wrote it. She wrote it on a bus. She had to fight to keep the track as long as it was because radio stations back then hated anything over three minutes.

The lyrics are deceptively simple. "We were poor but we had love." It sounds like a cliché until you realize she was one of eight children living in a space smaller than a modern two-car garage.

What made her perspective as the daughter of a coal miner so radical wasn't just the poverty; it was the honesty about what followed. She married Doolittle Lynn when she was roughly 15 years old. Some records say 13, but birth certificates from that era in Kentucky are notoriously messy. By the time she was 18, she had three kids. By 20, she had four. Most people in that situation stay in the hollow. They repeat the cycle. Loretta didn't just break the cycle; she brought the hollow with her to the Grand Ole Opry and refused to polish it up for the city folks.

Why the Song "Coal Miner's Daughter" Broke the Rules

In 1970, country music was trying to go "Nashville Sound." It wanted strings. It wanted polish. It wanted to sound like pop music with a slight drawl. Then comes this track that is unapologetically rural.

✨ Don't miss: Bea Alonzo and Boyfriend Vincent Co: What Really Happened Behind the Scenes

The song actually functions as a historical document. She mentions the "Blue Ridge Mountains" and the "workin' man." But more importantly, she mentions the "mommy" who "read the Bible by the coal oil lamp." That detail—the coal oil lamp—is a massive marker of time and place. It tells you they didn't have electricity. It tells you they were living in a pre-industrial pocket of America while the rest of the country was moving into the space age.

- The Instrumentation: It’s sparse. The banjo isn't there to be "twangy"; it's there because that's the sound of the mountains.

- The Narrative Arc: It doesn't complain. That’s the most "Appalachian" thing about it. There is a stoicism in being a daughter of a coal miner that rejects pity.

- The Impact: It hit Number 1 on the Billboard Country charts and eventually became her signature. It gave a voice to a demographic that felt invisible during the social upheavals of the late 60s and early 70s.

The Reality of Life in Butcher Hollow

Let's get real about the geography. Butcher Hollow—often pronounced "Holler"—is part of Johnson County. It’s rugged. Even today, if you visit the Loretta Lynn homeplace, you realize how far removed it is from the "civilized" world.

Her father, Pappy Webb, eventually died of black lung (Coal Workers' Pneumoconiosis). This is the dark side of the daughter of a coal miner narrative that doesn't always make it into the upbeat radio edits. The industry that fed the family also killed the father. Loretta saw this. She lived through the "Company Store" system, where miners were often paid in scrip rather than US currency. Scrip was basically "Monopoly money" that could only be spent at the store owned by the coal company. It was a form of debt slavery.

When she sings about her daddy working all night in the mines and all day in the cornfields, she isn't exaggerating for the sake of a rhyme. That was the only way to survive. The "corn" wasn't for a hobby garden. It was for dinner. Every night.

The Shift from Poverty to Power

Loretta's transition from a Kentucky housewife to a country superstar is the stuff of legends, but it’s often sanitized. It was gritty. She and Doo drove from radio station to radio station, literally begging DJs to play her first record, "Honky Tonk Girl." They slept in the car. They ate bologna sandwiches.

But her identity as a daughter of a coal miner gave her a "BS detector" that served her well in the music industry. She didn't take crap from executives. She wrote songs about birth control ("The Pill"), double standards in marriage ("Rated X"), and telling off mistresses ("Fist City"). These weren't "polite" songs. They were the songs of a woman who had seen the hardest parts of life and decided she didn't have anything left to be afraid of.

🔗 Read more: What Really Happened With Dane Witherspoon: His Life and Passing Explained

People often forget how many times she was banned. "The Pill" was banned by dozens of radio stations. Loretta's response? She didn't care. She knew the women in the hollows and the trailer parks were buying the record anyway because she was speaking their truth. She was the first woman in country music to really talk about the female experience in a way that wasn't subservient.

The 1980 Film and the Sissy Spacek Factor

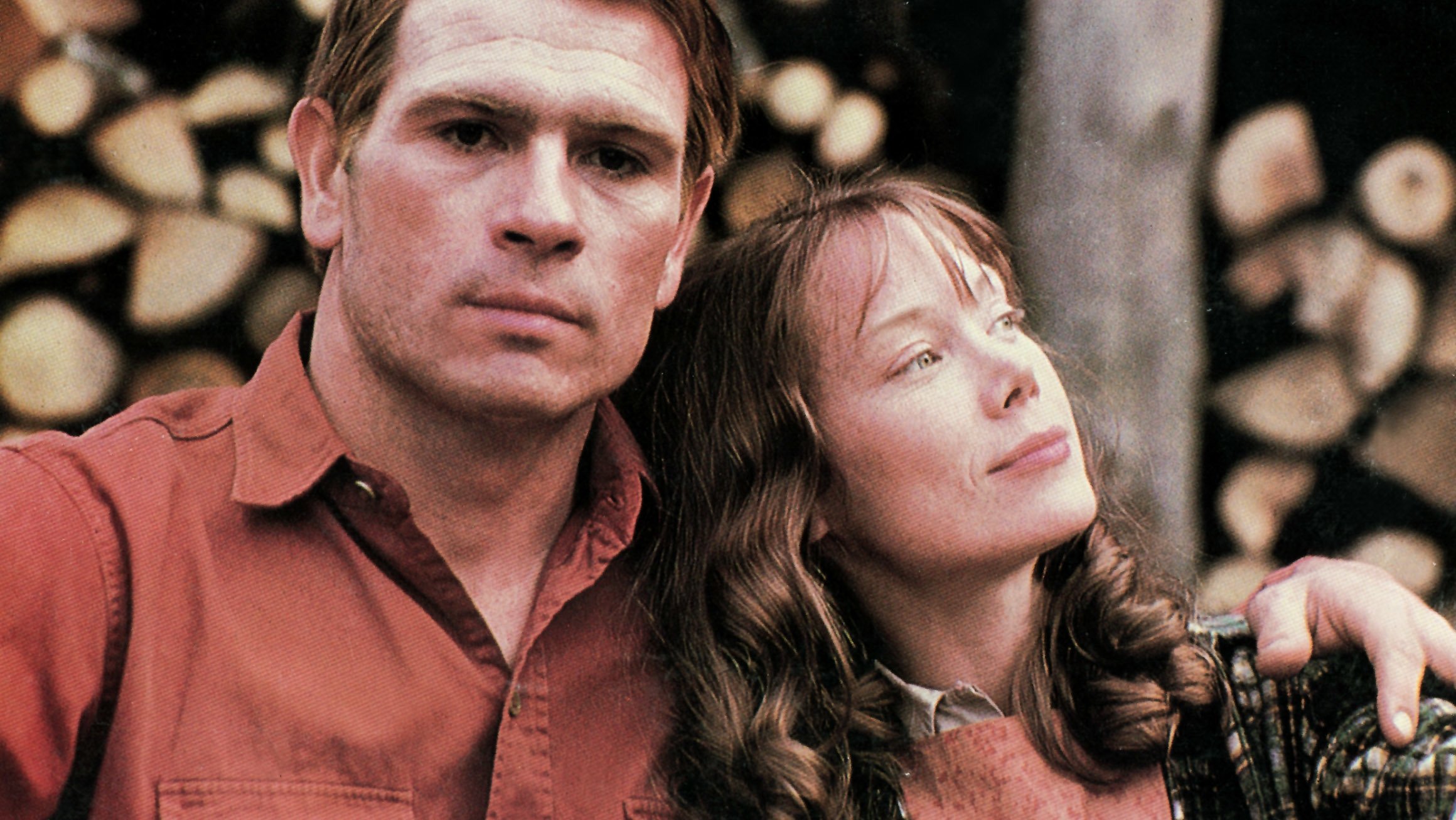

You can't talk about the daughter of a coal miner without mentioning the movie. It’s one of the few biopics that actually gets the atmosphere right. Tommy Lee Jones as Doolittle Lynn captured that complicated, often volatile, but deeply bonded relationship.

The film did something crucial: it showed the transition of the landscape. It showed the mud. It showed the grayness of the mining towns. It won an Academy Award because it didn't treat the subject matter like a "rags to riches" fairy tale. It treated it like a survival story.

Loretta personally picked Sissy Spacek for the role after seeing a photo of her. She didn't even know if Sissy could sing. As it turned out, Spacek did all her own singing for the film, which added a layer of authenticity that a lip-synced performance would have killed. That film cemented the daughter of a coal miner as a permanent fixture in the American mythos.

Nuance: The Relationship with Doolittle Lynn

The "story" often paints Doo as the hero who got her out of the hollow. The reality is more jagged. He was an alcoholic. He cheated. He was often physically and emotionally rough. But he was also the one who bought her her first guitar (a $17 Harmony) and told her she was better than anyone on the radio.

This complexity is part of the daughter of a coal miner identity. It’s about loyalty to people who are flawed because, in that environment, loyalty is the only currency you have. Loretta didn't leave him. She stayed until he died in 1996. She argued that without his pushiness, she would have remained a housewife in Washington state (where they moved after Kentucky).

💡 You might also like: Why Taylor Swift People Mag Covers Actually Define Her Career Eras

Practical Legacy: What We Can Learn Today

So, why does this matter in 2026? Why are we still talking about a woman from a defunct mining camp?

Because the "Coal Miner's Daughter" ethos is about authentic storytelling. In an era of AI-generated lyrics and over-produced social media personas, the raw, unfiltered honesty of Loretta Lynn is a blueprint for anyone trying to build a real connection with an audience.

She didn't try to hide her "country." She didn't take elocution lessons to lose her accent. She leaned into it.

Key Takeaways from the Life of a Coal Miner's Daughter:

- Own Your Origin Story: Don't sanitize your past. The parts you're embarrassed of—the "wallpaper made of newspapers"—are usually the parts people will relate to the most.

- Vulnerability is a Power Move: Writing about things like "The Pill" or marital strife wasn't "safe," but it was necessary. If you aren't saying something that might get you "banned," are you even saying anything?

- Hard Work isn't a Choice: For the Webb family, work was survival. Transferring that work ethic into a creative field is how you go from a $17 guitar to a 1,500-acre estate in Hurricane Mills.

The End of an Era

When Loretta passed away at her ranch in Tennessee, it felt like the end of a specific type of American history. We don't really have "coal miner's daughters" in the same way anymore. The industry has changed, the geography has changed, and the music industry is a different beast entirely.

But the core of the message remains. Being a daughter of a coal miner wasn't about the coal. It was about the dignity of the person holding the shovel. It was about the idea that where you start has zero bearing on where you can end up, provided you're willing to sing your truth the whole way there.

If you want to truly understand this legacy, stop reading articles and go listen to the Van Lear Rose album she did with Jack White in 2004. It’s raw, it’s loud, and it proves that even in her 70s, she was still that girl from Butcher Hollow who wasn't afraid to make a little noise.

Next Steps for the Interested:

- Listen to the "Coal Miner's Daughter" original 1970 recording: Pay attention to the steel guitar and the specific phrasing of "Butcher Holler."

- Watch the 1980 film: It is currently streaming on several major platforms and remains the gold standard for musical biopics.

- Research the Appalachian Coal Wars: To understand the "why" behind her father's struggle, look into the history of unionization in Kentucky and West Virginia during the early 20th century.

- Explore the "Van Lear Rose" Album: See how a 70-year-old Loretta Lynn influenced the garage rock scene, proving her story is timeless and genre-defiant.