William Lamb, better known as Lord Melbourne, wasn't exactly your typical power-hungry politician. Honestly, he kind of stumbled into the top job. Most people today only know him because of the Netflix shows or period dramas where he's portrayed as a brooding mentor to a young Queen Victoria. But the real Lord Melbourne Prime Minister was way more complicated—and arguably more cynical—than the TV version. He was a man who hated change, loved a good scandal, and somehow managed to hold the British Empire together during one of its most volatile transitions.

He didn't want to be a hero. He just wanted things to stay quiet.

A Career Built on Doing as Little as Possible

It sounds like a joke, but Melbourne’s political philosophy was basically "why bother?" He famously asked, "Why not leave it alone?" whenever someone proposed a massive new law. You have to understand the era. The 1830s were chaotic. Britain was on the verge of a revolution. The Industrial Revolution was tearing up the old social fabric, and people were demanding the right to vote. Melbourne, a Whig, found himself leading a party that was supposed to be "progressive," even though he personally thought most progress was a bit of a nuisance.

His rise to the premiership in 1834 was less of a triumph and more of a "well, who else is left?" situation. King William IV actually fired him once, only to realize he had to hire him back because the Conservatives couldn't form a government. It was messy.

Melbourne’s style was effortless. Maybe too effortless. He was known for lounging on sofas during meetings, sometimes even appearing to nap while people discussed the fate of the nation. But don't let the laziness fool you. He was incredibly sharp. He knew exactly how to balance the egos in his cabinet, and he had a terrifyingly good grasp of human nature. He wasn't trying to build a utopia; he was trying to prevent a collapse.

The Queen's Favorite Teacher

When 18-year-old Victoria took the throne in 1837, she was lost. Her mother had kept her isolated, and she didn't know the first thing about running a country. Enter Lord Melbourne Prime Minister.

✨ Don't miss: The CIA Stars on the Wall: What the Memorial Really Represents

He became her private secretary, her tutor, and her father figure all rolled into one. They spent hours together every day. He taught her how the British constitution worked, sure, but he also taught her how to handle difficult ministers and how to navigate the shark-infested waters of European royalty. Victoria was obsessed with him. In her diaries, she referred to him as "Lord M" and constantly praised his wit and kindness.

- He gave her confidence.

- He buffered her from political attacks.

- But he also made her a bit too partisan.

Because Victoria loved Melbourne so much, she hated the Tories (the opposition party). This led to the "Bedchamber Crisis" of 1839. When Melbourne tried to resign, the Tory leader Robert Peel said he’d only take the job if Victoria fired her ladies-in-waiting, who were all married to Melbourne’s Whig friends. Victoria refused. She threw a royal tantrum. Peel walked away, and Melbourne stayed in power for a few more years. It was a constitutional nightmare, but it showed just how deep their bond went.

Scandal, Divorce, and the Victorian Paparazzi

You can't talk about Melbourne without talking about his disastrous personal life. Long before he was the respectable Lord Melbourne Prime Minister, he was the husband of Lady Caroline Lamb.

She is the one who famously described Lord Byron as "mad, bad, and dangerous to know." Her very public affair with Byron was the talk of London. She once sent Byron a lock of her pubic hair. She tried to stab herself at a party. Melbourne stayed with her through most of it, which either makes him a saint or incredibly detached.

Then there was the Caroline Norton scandal. In 1836, George Norton sued Melbourne for "criminal conversation"—basically, he accused the Prime Minister of having an affair with his wife. It was the 19th-century version of a celebrity trial. The evidence was flimsy (mostly just notes Melbourne had sent her asking to visit), and the jury threw it out in seconds. But the damage to his reputation was real. He was a man constantly walking the line between high-society respectability and total social ruin.

🔗 Read more: Passive Resistance Explained: Why It Is Way More Than Just Standing Still

The Policy of "Wait and See"

While he was busy tutoring the Queen or dodging lawsuits, Melbourne actually oversaw some massive changes. He didn't like them, but he signed off on them.

The 1830s saw the Poor Law Amendment Act, which created the infamous workhouses. It was a brutal system, but Melbourne saw it as a necessary evil to keep the economy from tanking. He also dealt with the rise of Chartism—a massive working-class movement for voting rights. His response? He didn't want to give them the vote, but he didn't want to massacre them either. He used a mix of light repression and strategic waiting.

He also presided over the reduction of tithes in Ireland and the reform of municipal corporations. He wasn't a visionary like Gladstone or a bulldog like Palmerston. He was a stabilizer. He kept the ship steady while the world outside was screaming for a new captain.

Why Historians are Divided

If you ask a historian about Melbourne today, you'll get two very different answers. Some see him as a lazy aristocrat who held back progress and treated the Prime Ministership like a hobby. They point to his failure to address the crushing poverty of the era. Others, like David Cecil in his famous biography Lord M, see him as a nuanced, tragic figure. They argue that his moderation was exactly what Britain needed to avoid a violent revolution like the ones happening in France.

- Pros: Stability, mentorship of Victoria, prevented civil unrest.

- Cons: Cynicism toward reform, personal scandals, lack of economic vision.

The Long Shadow of Melbourne

By 1841, Melbourne’s luck ran out. His government was tired, and the country wanted change. Robert Peel finally took over, and Melbourne was pushed to the sidelines.

💡 You might also like: What Really Happened With the Women's Orchestra of Auschwitz

The hardest part for him wasn't losing power; it was losing Victoria. As she married Prince Albert, the Prince Consort slowly pushed Melbourne out of the Queen's inner circle. Albert found Melbourne’s casual attitude and scandalous past distasteful. It was a cold end to a warm friendship. Melbourne suffered a stroke in 1842 and spent his final years in a sort of lonely retirement, watching from a distance as the Victorian era he helped create moved on without him.

He died in 1848, the "Year of Revolutions." It was a fitting time for him to go. The old world he represented was finally disappearing.

Lessons from the Melbourne Era

What can we actually learn from Lord Melbourne Prime Minister? He wasn't a perfect man, and he certainly wasn't a perfect leader. But he understood something that many modern politicians forget: timing is everything.

Sometimes, the best thing a leader can do is stay calm and wait for the fever to break. He taught us that mentorship matters. Without Melbourne, Victoria might have been a much more volatile, less successful monarch. He smoothed out her sharp edges, even if he did it while lounging on a silk sofa with a glass of sherry.

If you’re looking to understand British history, don’t just look at the great reformers or the war heroes. Look at the people like Melbourne. The ones who kept the lights on while everyone else was trying to burn the house down.

How to Explore This Further

- Read the Diaries: Queen Victoria’s early journals are public. They offer a raw, unfiltered look at how much she leaned on Melbourne. It’s better than any historical fiction.

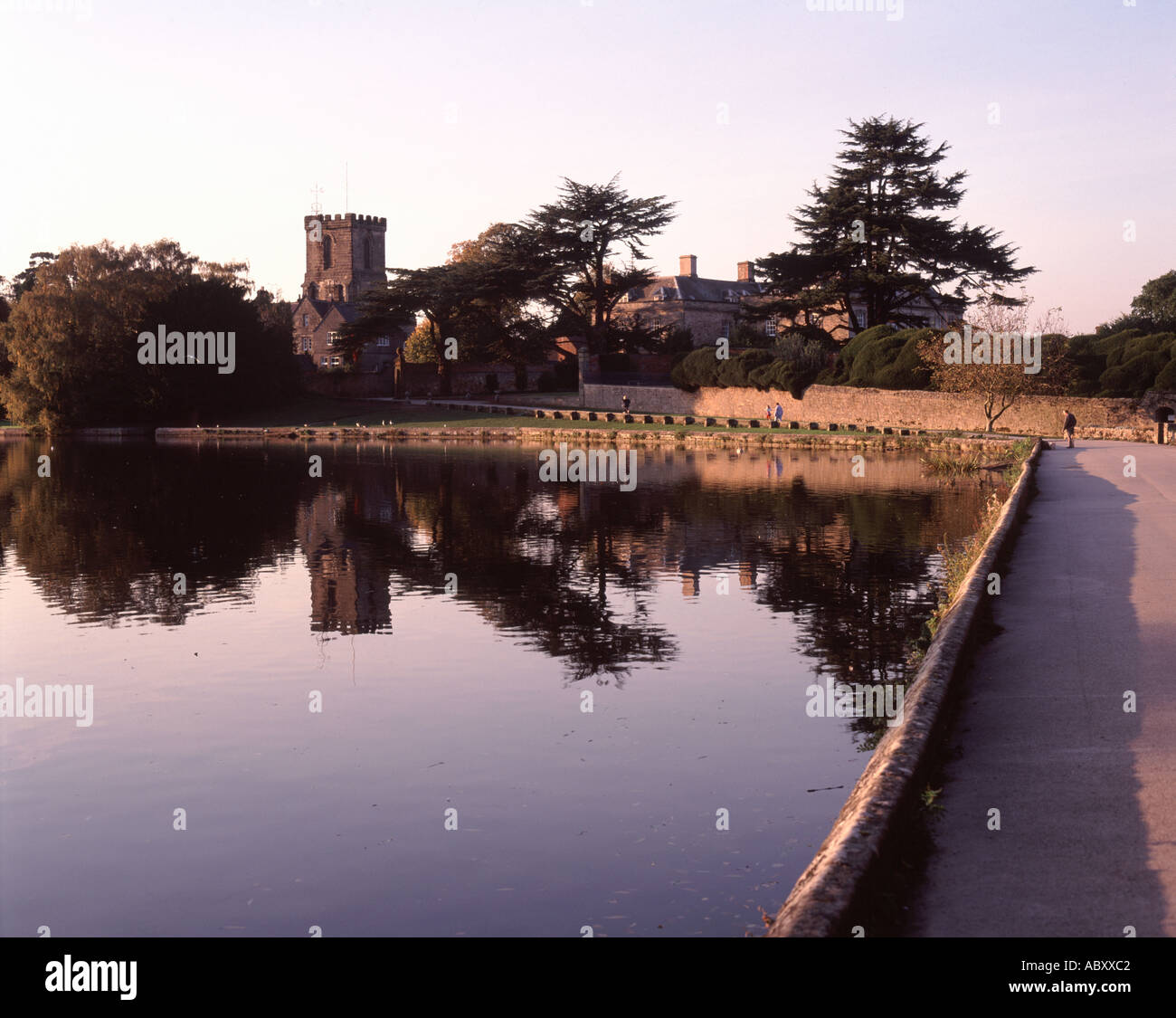

- Visit Brocket Hall: This was Melbourne’s family seat. Seeing the physical environment he lived in helps explain his "country gentleman" approach to world-altering politics.

- Study the 1832 Reform Act: While Melbourne was reluctant, this act set the stage for his entire premiership. Understanding the "Great Reform" is key to understanding why he was so desperate to slow things down afterwards.

- Compare and Contrast: Look at Melbourne alongside his successor, Robert Peel. Peel was a technocrat; Melbourne was an artist of human relationships. Seeing how they handled the same problems (like the Corn Laws) reveals the massive shift in British leadership styles during the mid-1800s.

History isn't just a list of dates. It's a collection of weird, flawed people trying to figure things out as they go. Melbourne was the king of "figuring it out." He didn't have a grand plan, but he had a steady hand. In a world that's always rushing toward the next big thing, there's something almost refreshing about a man who just wanted to leave things alone.