It looks easy. You just tilt the head, right? You’re drawing a character, or maybe you're posing for a brand photoshoot, and you think a simple glance away from the lens will add that "moody" or "candid" vibe. Then you see the result. The neck looks like a strained pipe, the eyes are buried in the bridge of the nose, and the whole thing feels stiff. Honestly, the looking to the side reference pose is one of the most deceptively difficult positions to master in visual arts and photography because it forces you to deal with extreme foreshortening and the complex mechanics of the sternocleidomastoid muscle.

If you’ve ever wondered why your sketches of this pose look like the head is sliding off the shoulders, you aren’t alone. It’s a common frustration. Artists like Andrew Loomis and George Bridgman spent entire chapters of their lives trying to explain how the skull sits on the pivot of the neck. When you look to the side, you aren't just moving your eyes; you’re rotating a heavy sphere on a delicate column.

The Anatomy of a Sideways Glance

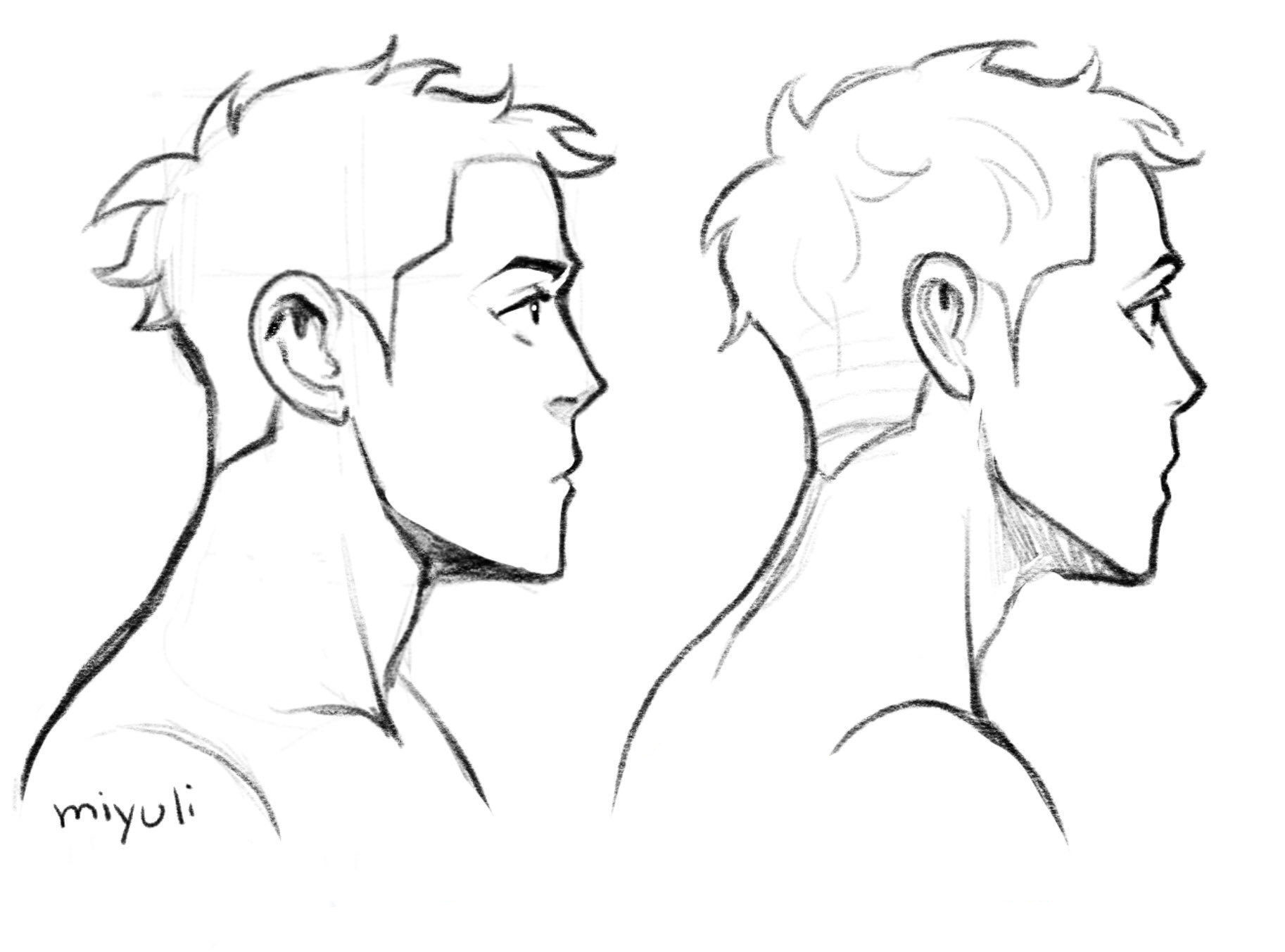

Stop thinking about the face as a flat plane. It’s a 3D object. When a person uses a looking to the side reference pose, the midline of the face shifts. Most beginners make the mistake of keeping the features centered on the head while just "pointing" the nose to the left or right. It doesn't work. You end up with a Picasso-style mess that feels unintentional.

Think about the "wrapping" effect. Everything—the eyes, the lips, the brow line—has to follow the curve of the skull. If the head is turned 45 degrees, the eye furthest from the viewer becomes narrower. We call this foreshortening. You lose the outer corner of that far eye. It basically disappears behind the bridge of the nose. If you draw both eyes the same size, the face will look broken.

Then there's the neck. People forget the neck. When you turn your head, that thick muscle—the one that runs from behind your ear down to your collarbone—pops out. It creates a diagonal line that defines the entire gesture. Without that tension, the head looks like it’s floating. Proko, a well-known art educator, often emphasizes that the "corner" of the jaw also changes drastically depending on whether the chin is tilted up or down during that side-look.

🔗 Read more: God Willing and the Creek Don't Rise: The True Story Behind the Phrase Most People Get Wrong

Why Photographers Love (and Hate) This Angle

In portrait photography, the "three-quarter view" or a full side profile is a staple. It creates depth. It adds drama. But it's risky. If you have your subject look too far to the side, you see too much of the whites of their eyes. This is sometimes called the "shark eye" effect. It looks creepy. You want the iris to remain central or slightly offset, not shoved into the corner of the socket.

Lighting also gets weird here. When someone is in a looking to the side reference pose, the nose often casts a long, sharp shadow across the far cheek. In classic Rembrandt lighting, you're looking for that tiny triangle of light on the shadowed side. If the turn is too sharp, that triangle disappears, and you’re left with a "split lighting" setup that can look way too aggressive for a standard portrait.

Breaking the "Stiff Neck" Syndrome

Ever seen a reference photo where the person looks like they’re in a neck brace? That’s usually because the shoulders are squared to the front while the head is cranked 90 degrees. It’s unnatural. Real human movement is fluid. If you’re looking to the side, your shoulders usually follow at least 10 or 15 degrees.

Try it right now. Turn your head to the right as far as it goes. Feel that pull in your left shoulder? Your body wants to rotate with you. When capturing or drawing a looking to the side reference pose, subtle shoulder rotation makes the difference between a "statue" and a "person."

💡 You might also like: Kiko Japanese Restaurant Plantation: Why This Local Spot Still Wins the Sushi Game

Common Mistakes to Avoid

- The Vanishing Ear: People often place the ear too far back. In a profile or side-looking view, the ear is actually quite central to the mass of the head.

- The Flat Nose: Remember that the nose has a side plane. When the head turns, you should see the side of the bridge, not just the "front" of the nostrils.

- The Eye Level: Most people accidentally tilt the eyes when they turn the head. Unless the character is specifically tilting their head, those eyes should stay on a level horizontal plane.

Real-World Applications in Character Design

In 3D modeling and animation, the "side look" is used to convey "The Internal Monologue." Think about cinematic shots in games like The Last of Us or God of War. When a character looks away from the person they are talking to, it signals doubt, shame, or deep thought.

Concept artists use the looking to the side reference pose to show off a character's profile—specifically the jawline and the "silhouette" of the hair. If you only ever draw characters from the front, they lack personality. A side glance provides a "lost edge" that allows the viewer's imagination to fill in the gaps. It's more engaging. It’s more mysterious.

How to Find Better References

Don't just Google "man looking to the side." You’ll get generic, over-edited stock photos that lack real muscular tension. Instead, look for:

- Film Stills: Search for "cinematography side profile." Movies use lighting to emphasize the bone structure of this pose.

- Classical Sculpture: Look at Roman busts. These artists understood the weight of the head better than anyone.

- Life Drawing Sites: Websites like Line-of-Action or Adorkastock provide raw, unedited photos that show how skin actually folds and bunches around the neck during a turn.

The reality is that "perfect" isn't the goal. The goal is "believable." A human neck isn't a smooth cylinder; it’s a mess of tendons and skin. A side-looking pose should show a bit of that "mess." If it’s too clean, it’s boring. If it’s too distorted, it’s a monster. Finding that middle ground requires looking at real people—people with double chins when they turn, people with wrinkles, people whose eyes crinkle at the corners.

📖 Related: Green Emerald Day Massage: Why Your Body Actually Needs This Specific Therapy

Actionable Steps for Mastering the Pose

If you want to actually get good at this, stop theorizing and start doing. Here is how to actually improve your grasp of the looking to the side reference pose without wasting months of practice.

First, grab a mirror. Don't use a camera yet. Turn your head and watch how your neck muscles (the sternocleidomastoids) form a "V" shape toward your collarbone. Notice how your jawline disappears into your neck if you look down while looking to the side.

Second, practice the "Ghost Eye." Draw the eye that is furthest away first. Usually, people draw the "easy" eye and then realize they have no room for the second one. By starting with the foreshortened eye—the one partially hidden by the nose—you force yourself to map out the 3D space of the face correctly from the start.

Third, simplify the head into a block. Forget the eyes and mouth for a second. Draw a cube. Rotate that cube. If you can’t draw a cube in a looking to the side reference pose, you can’t draw a human head in that pose. The "planes of the head" are your best friend.

Finally, pay attention to the "negative space." Look at the shape of the air between the chin and the shoulder. In a side-looking pose, that gap tells the viewer exactly how much the head is tilted. If there’s no gap, the character looks hunched. If the gap is too large, they look like they have a "long neck" deformity. Adjust that spacing until the silhouette feels balanced and weighted.

Mastering this isn't about some secret trick. It's about realizing that the head is a heavy object balanced on a flexible pole. Once you respect the physics of that rotation, your references will start looking like people instead of distorted mannequins.