Music is a fickle beast. Sometimes a songwriter pours their soul into a melody only to watch the world turn it into something unrecognizable, and honestly, that’s exactly what happened with Look What They Done To My Song Ma. Most people know it as a catchy, almost whimsical folk-pop tune. You’ve probably heard it in a commercial for oatmeal or a cleaning product at some point. It’s got that bouncy rhythm that feels safe. But if you actually listen—really listen—to what Melanie Safka was saying, you’ll realize it’s one of the most passive-aggressive, heartbroken "screw you" letters ever written to the music industry.

Melanie was a powerhouse. She was the girl who stood on the stage at Woodstock when it was raining, literally inspiring the "candles in the rain" movement, yet history often treats her like a footnote. This song is the proof of why she felt that way.

The origin of Look What They Done To My Song Ma

Back in 1970, Melanie was dealing with the crushing weight of being a "product." The industry didn't want a poet; they wanted a hit-maker. When she wrote Look What They Done To My Song Ma, she wasn't just humming a tune. She was venting. She was frustrated that her creative output was being sliced, diced, and rearranged by producers who cared more about radio play than her artistic intent.

It’s a meta-commentary. Think about that for a second. She wrote a song about how people were ruining her songs, and then—in a twist of irony that would be funny if it wasn't so annoying—the industry turned that song into a commercial jingle. It’s peak record label behavior.

The lyrics mention how it's the only thing she could do "halfway good," and she laments that if her mom could see her now, she’d be crushed. It’s self-deprecating but sharp. She even throws in a verse in French. Why? Because the industry thought "international appeal" was a gimmick they could exploit. Melanie was basically saying, "Fine, you want me to be a puppet? Here's your puppet song."

Why the covers changed everything

When you look at the covers of Look What They Done To My Song Ma, you see the evolution of how the public perceives a "hit." Ray Charles took a crack at it. The New Seekers made it a massive success in the UK. Miley Cyrus even brought it back for her Backyard Sessions, proving the melody has legs that span generations.

🔗 Read more: Jack Blocker American Idol Journey: What Most People Get Wrong

But each version strips away a little bit of the original's bite. Ray Charles gave it soul, which worked, because Ray could make a grocery list sound like a masterpiece. The New Seekers, however, turned it into a polished, upbeat anthem. They took the "Ma" out of the gutter and put her in a Sunday dress. It’s fascinating how a song about the destruction of art can be so successfully... well, sanitized.

- The Original (1970): Raw, quirky, and deeply cynical.

- The New Seekers Version: Polished, harmony-heavy, and radio-friendly.

- The Miley Cyrus Cover: Gritty, acoustic, and closer to Melanie's original spirit than most.

Melanie once mentioned in interviews that she felt like she was constantly fighting to be taken seriously as a songwriter. In the late 60s and early 70s, the "girl with a guitar" trope was often dismissed as "cute." She wasn't trying to be cute. She was trying to be heard.

The technical brilliance of a "simple" song

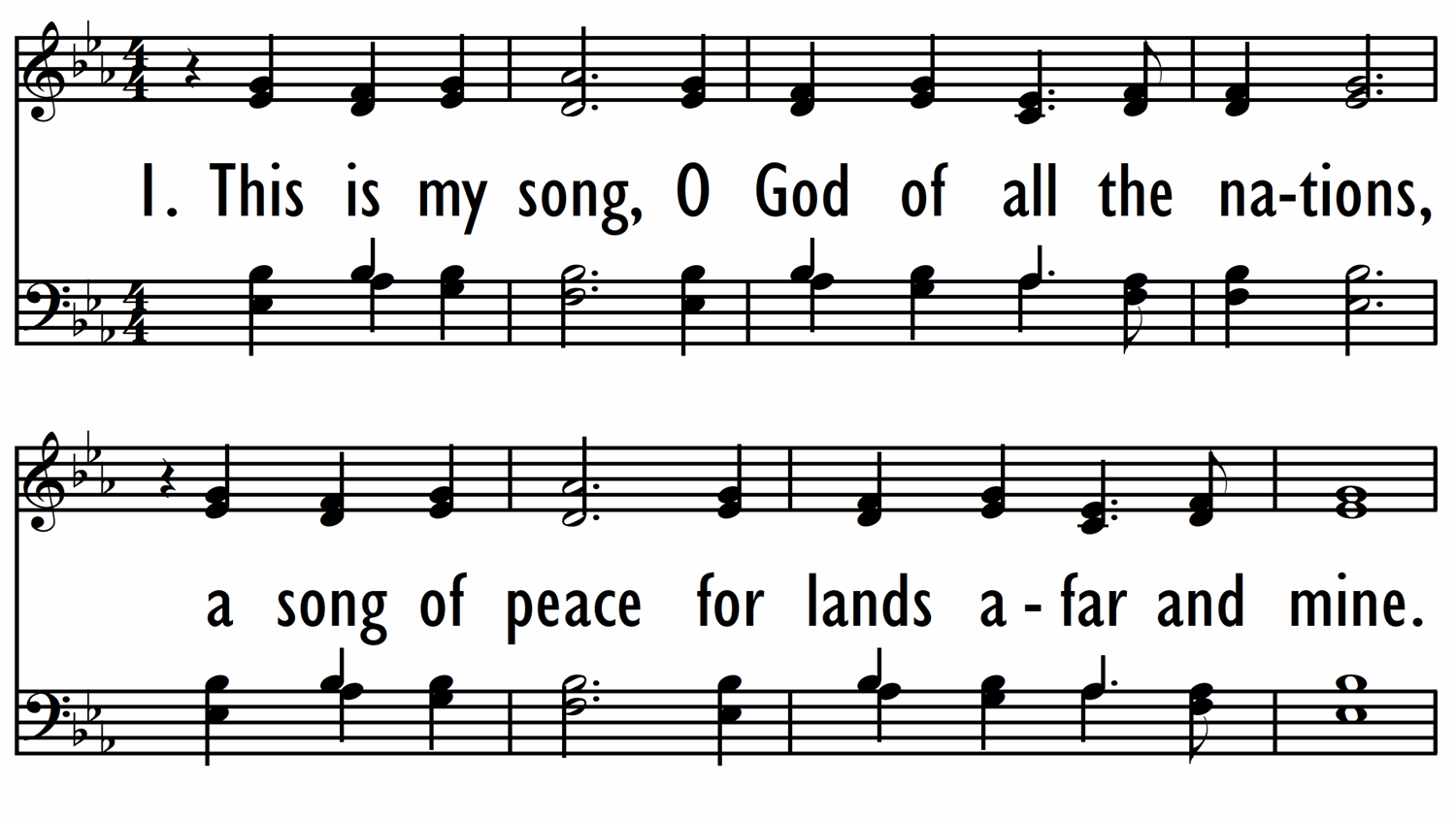

Let’s get nerdy for a minute. On paper, the song is simple. It’s a basic progression that relies on a repetitive hook. But the way Melanie uses her voice—that raspy, emotive vibrato—is what makes it a masterclass in folk-pop. She starts quiet. She builds. By the end, she’s almost shouting. It’s a controlled tantrum.

$I \rightarrow IV \rightarrow V$ progressions are the bread and butter of folk music, but Melanie’s phrasing is what breaks the mold. She lingers on words like "ma" and "brain" in a way that feels uncomfortable. It’s not "pretty" singing. It’s honest singing.

The commercial irony

You cannot talk about Look What They Done To My Song Ma without talking about its life in advertising. In the 1980s, the song was famously adapted for the New Twinings Herbal Tea commercials and later for Life Cereal. It became "Look what they’ve done to my oatmeal."

💡 You might also like: Why American Beauty by the Grateful Dead is Still the Gold Standard of Americana

Can you imagine?

Melanie writes a song about the commercialization and degradation of her art, and ten years later, it’s being used to sell breakfast cereal. It is the ultimate example of the industry proving her point. She was right all along. They did do something to her song. They turned it into a 30-second spot for whole grains.

Some people think she must have hated it. Honestly, it’s complicated. Songwriters need to eat. Licensing a song for a commercial can provide the financial freedom to keep making art. But there’s no denying the spiritual disconnect between the lyrics "it's turning out all wrong" and a smiling family eating cereal.

Redefining Melanie’s legacy

Melanie Safka passed away in early 2024, leaving behind a massive catalog, but Look What They Done To My Song Ma remains her calling card alongside "Brand New Key." People often dismiss her as a "hippie" singer, but that’s a lazy categorization. She was an independent spirit who started her own record label (Neighborhood Records) when she felt the big guys weren't listening.

She was one of the first women to really take control of her business destiny in that era. When you listen to the song now, you should hear it as a manifesto. It’s a warning to other artists. It’s a reminder that once you put your art into the world, you lose control of it.

📖 Related: Why October London Make Me Wanna Is the Soul Revival We Actually Needed

The song isn't just about music. It’s about identity. It’s about that feeling we all get when we work hard on something, only to have a boss, a parent, or a "system" tell us it’s not quite right and needs to be changed. It’s the universal cry of the creator.

How to actually appreciate this track today

If you want to understand the impact of this song, don't just stream the most popular version on Spotify. Dig a little deeper.

- Listen to the 1970 studio version first. Pay attention to the French verse. It’s not just for show; it’s a jab at the pretentiousness of the music scene.

- Watch the live footage from the early 70s. You can see the intensity in Melanie's eyes. She isn't smiling through the lyrics. She’s grit-teeth performing.

- Compare it to the covers. Notice what’s missing. Usually, it’s the desperation. Most covers make it sound like a fun sing-along. The original sounds like a cry for help.

The song’s longevity isn't because of the "ma-ma-ma-ma" hook. It’s because the sentiment is timeless. As long as there are people trying to make things and other people trying to sell those things, Look What They Done To My Song Ma will be relevant.

Actionable Insights for Music Lovers and Artists

If you’re an aspiring musician or just someone who cares about where their music comes from, here’s the takeaway from Melanie’s struggle:

- Own your masters if you can. Melanie fought for independence because she saw how her work was being manipulated. In the modern era of streaming, holding onto your rights is the only way to prevent your "song" from being turned into something you hate.

- Don't ignore the subtext. Just because a song sounds happy doesn't mean it is. The 1970s was a golden age of "sad songs disguised as pop hits."

- Support the source. When a classic song gets revived by a modern artist, go back and check out the original creator. Melanie’s discography is deep, weird, and much more experimental than her radio hits suggest.

The next time you hear that familiar melody, remember the woman behind it. She wasn't just complaining. She was telling the truth about how the world treats creativity. It’s a song about loss, disguised as a ditty, and that’s exactly why it still works fifty years later. Take the time to listen to her live performances from the BBC or her 1970s TV appearances—you’ll hear a voice that refused to be silenced, even when they were trying to turn her song into something else entirely.