If you stood on Warwick Road today, you’d see a massive, gaping hole in the ground. It’s a void. For decades, that space was occupied by a shimmering, Art Deco behemoth that defined the West London skyline. London’s Earls Court Arena wasn't just a building; it was the city's primary heartbeat for everything from high-stakes volleyball to David Bowie’s legendary stage antics. It’s gone now. Demolished. But the ghost of the place still haunts the London property market and the memories of anyone who ever spilled a pint there.

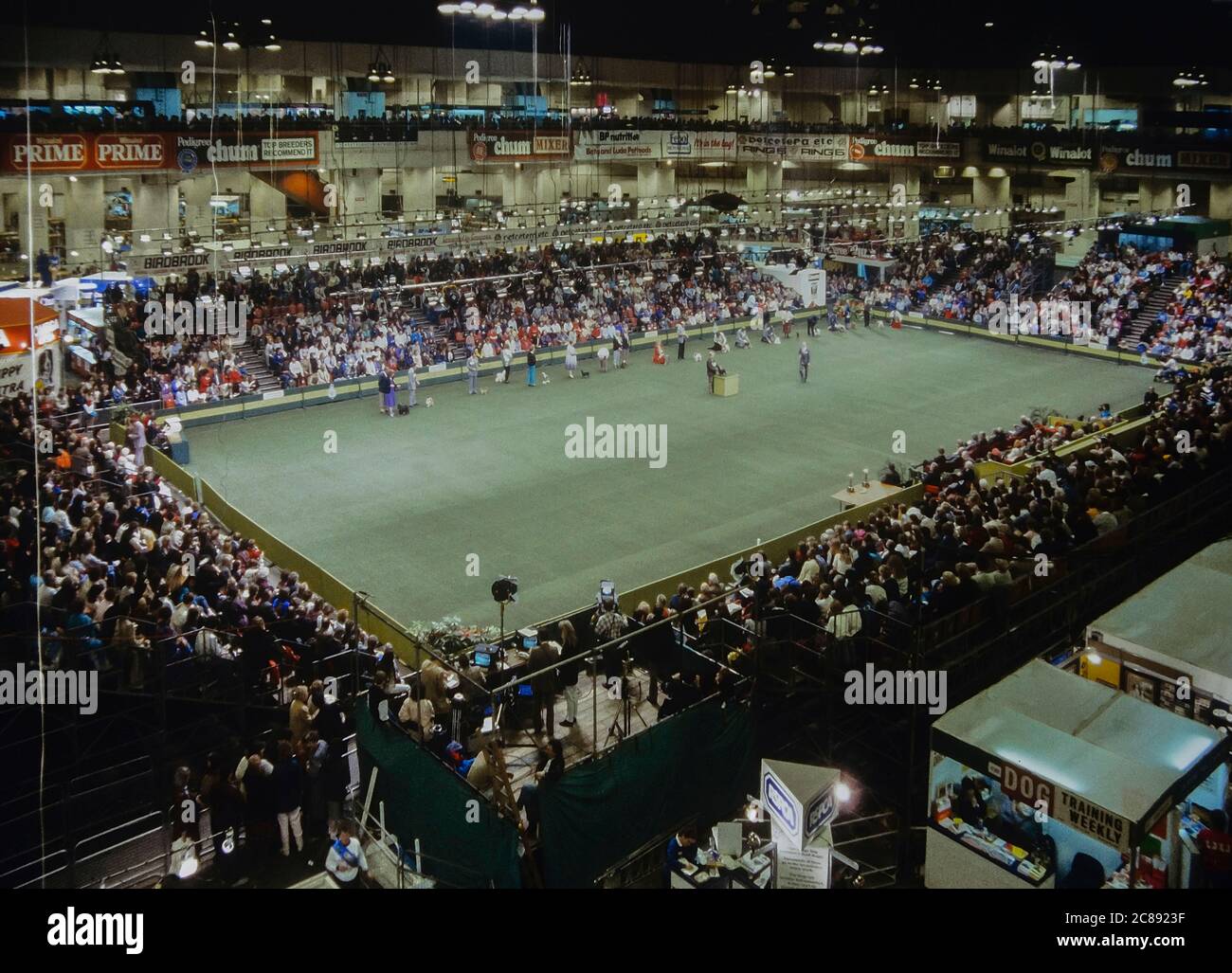

The scale of the place was genuinely ridiculous. We’re talking about a venue that could swallow 19,000 people and still have room for a literal indoor lake. That’s not an exaggeration. Architect C. Howard Crane designed the second iteration (Earls Court II) with a mechanical floor that could be lowered to reveal a massive pool. They used it for the Royal Tournament and boat shows. You just don't see that kind of ambition in modern, soulless arenas anymore.

The Night the Lights Went Out at London’s Earls Court Arena

Most people remember the end. The final curtain came down in 2014, and honestly, it felt like a betrayal to many Londoners. The last gig was Bombay Bicycle Club. It was a fitting, if somewhat understated, farewell to a venue that had hosted the biggest names in human history.

Think about the 1948 Olympics. London was still recovering from the Blitz, rationing was a grim reality, and yet, London’s Earls Court Arena stepped up to host the boxing, gymnastics, wrestling, and weightlifting. It was a symbol of resilience. Fast forward to the 2012 Olympics, and it was back in the spotlight for volleyball. Not many buildings get to bookend the city's Olympic history like that.

Why did they tear it down?

Money. Pure and simple. The site sits on some of the most valuable real estate on the planet, bridging the gap between Kensington and Chelsea. The developers, Capco (Capital & Counties Properties), saw more value in luxury apartments than in a historic venue that was, admittedly, getting a bit rough around the edges.

✨ Don't miss: The Lil Wayne Tracklist for Tha Carter 3: What Most People Get Wrong

Critics argued it was "architectural vandalism." They weren't necessarily wrong. The Arena was a Grade II listed candidate that never quite got the protection it deserved. The demolition process itself was a slow-motion car crash that took years, involving the removal of massive concrete beams over the District and Piccadilly tube lines.

More Than Just a Concert Hall

If you only think of London’s Earls Court Arena as a place for music, you’re missing half the story. It was the home of the British Motor Show for decades. It hosted the Ideal Home Exhibition, where generations of Brits went to see the "house of the future."

It was versatile. One week it was a dirt track for motocross, the next it was a high-fashion runway.

Pink Floyd’s The Wall tour in 1980 and 1981 basically lived there. They performed 31 dates at the venue. If you talk to any local over the age of 50, they likely have a story about seeing the giant inflatable pig floating above the West Cromwell Road. It was a sensory overload that defined an era of prog-rock excess. Led Zeppelin played five nights there in 1975. Those shows are still traded as legendary bootlegs today.

🔗 Read more: Songs by Tyler Childers: What Most People Get Wrong

The Logistics of a Behemoth

The arena was a nightmare to load into. Roadies hated it. Fans loved it. The acoustics were, let’s be real, kinda hit or miss depending on where you were sat. If you were in the nosebleeds, you were basically listening to the music through a tin can, but the atmosphere? Unmatched.

The structure itself was a marvel of pre-war engineering. It used over 40,000 tons of concrete. The sheer weight of the building meant that when it came time to pull it down, they couldn't just use a wrecking ball. They had to use a massive "crawler crane"—one of the largest in the world—to pick it apart piece by piece.

The Controversy That Won't Die

The redevelopment project, now known as the Earls Court Development Company, has been a political football for over a decade. The original plans called for thousands of new homes, but the "affordable" percentage was a sticking point. Residents in the nearby North End Road felt squeezed out.

There's a specific kind of grief that comes with losing a landmark. It’s not just about the bricks; it’s about the cultural footprint. When London’s Earls Court Arena disappeared, London lost a mid-sized-to-large capacity venue that hasn't really been replaced in the West End. Sure, we have the O2, but that’s all the way out in Greenwich. We have Wembley, but that's a trek. Earls Court was central. It was accessible.

💡 You might also like: Questions From Black Card Revoked: The Culture Test That Might Just Get You Roasted

A Quick Reality Check on the Site Today

If you visit the site in 2026, you'll see a lot of hoardings. The latest masterplan, led by Delancey and the Dutch pension fund APG, is trying to be more "community-focused" than the previous iterations. They’re promising a "clean and green" neighborhood with a massive park.

- The Void: The actual footprint of the arena remains largely undeveloped as infrastructure work continues.

- The Lost History: A small permanent exhibition or "heritage trail" has been discussed, but it’s cold comfort for those who want the venue back.

- The Future: We're looking at a 15-to-20-year build time before the site is fully "finished."

What We Learned From the Fall of Earls Court

The story of London’s Earls Court Arena is a cautionary tale about urban planning. It shows how easily a city can lose its soul when property values outstrip cultural value. It also highlights the sheer difficulty of maintaining massive, multi-purpose 20th-century structures in a 21st-century economy.

Could it have been saved? Probably. But it would have required a level of public investment that simply wasn't on the table in the post-2008 austerity years.

Actionable Insights for the Urban Explorer or Historian

If you’re interested in what’s left of this era of London history, don’t just stare at the construction site. Look at the surrounding area.

- Visit the Brompton Cemetery: It’s right next door. Many of the people who built the original Victorian Earls Court grounds are buried there. It offers the best vantage point to see the scale of the redevelopment.

- Check the Archives: The Kensington Central Library holds an incredible collection of photos and programs from the Arena’s heyday.

- Support Local Venues: If you don't want the remaining mid-sized venues in London to go the way of Earls Court, go to shows at the Eventim Apollo (Hammersmith) or the Royal Albert Hall. These are the survivors.

- Follow the Planning Portal: If you’re a local, stay active on the Hammersmith & Fulham and Kensington & Chelsea planning portals. The Earls Court site is still evolving, and public consultation actually matters now more than it did in 2012.

The arena is gone, but the legacy of the "Earls Court sound" and the sheer audacity of an indoor lake in the middle of London lives on in the city's DNA. It was a place where anything could happen, and for a few decades, it usually did.