You step out of the Tube at Oxford Circus and your first instinct is to take a deep breath of that crisp, morning air. Except, in London, it isn't always crisp. Sometimes it’s metallic. Occasionally, it’s a bit heavy. We’ve all seen the headlines about the "toxic" air, but if you look at the air quality index London data on a random Tuesday, it often looks... fine? Green. Maybe a splash of yellow. This disconnect is exactly where the confusion starts for most Londoners.

The truth is that London’s air is a massive, shifting puzzle. One street is a literal wind tunnel of fresh air from the Thames; the next is a canyon of trapped nitrogen dioxide.

London has changed. Ten years ago, the city was regularly breaking legal limits for pollutants within the first week of January. Now, thanks to things like the Ultra Low Emission Zone (ULEZ) and a massive shift toward electric buses, the situation is drastically different, yet still stubbornly complex. Understanding the index isn't just about checking an app before your morning jog; it's about knowing which specific pollutants are lurking at shoulder height while you're walking the dog.

The Reality of the Air Quality Index London Today

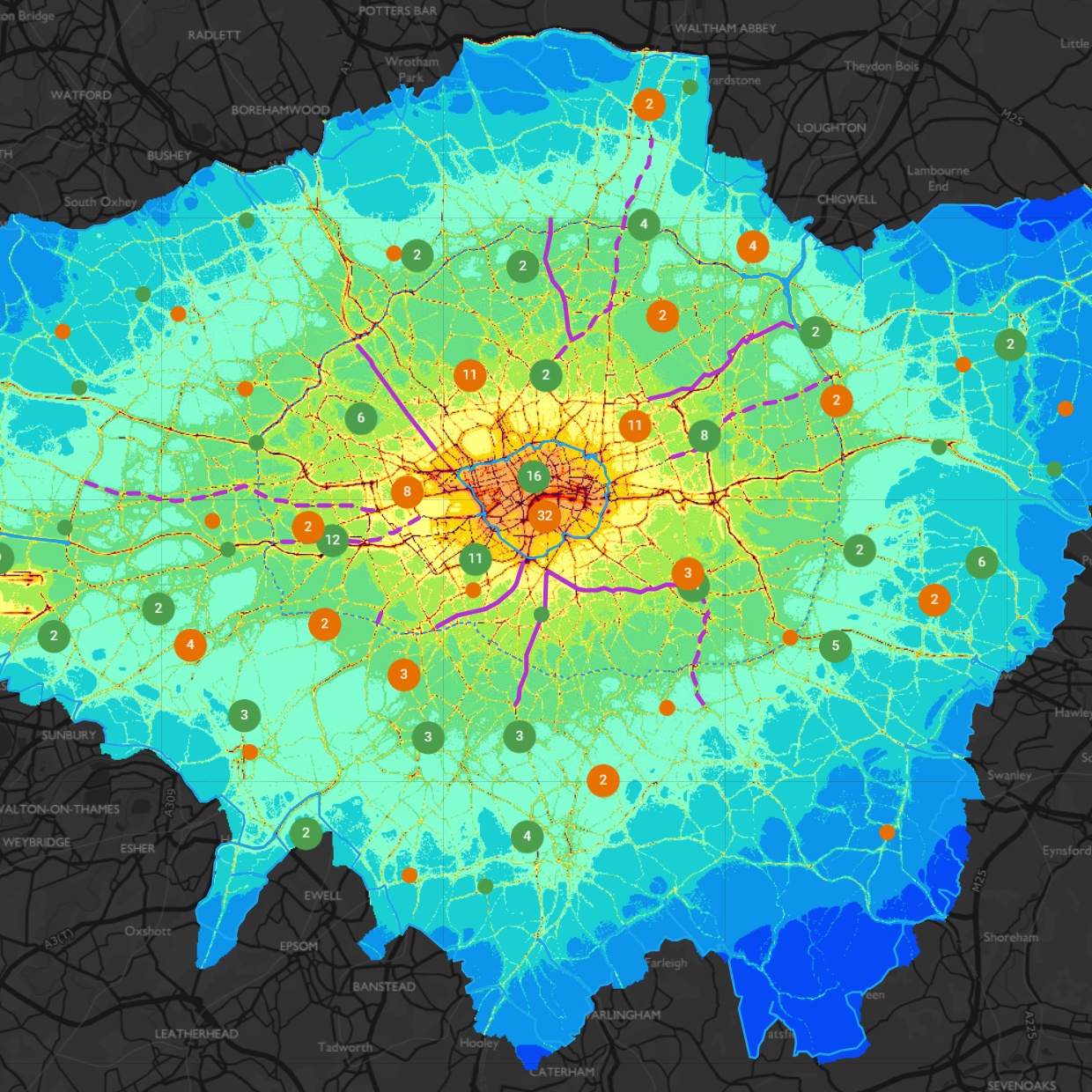

If you’re looking at the London Air Quality Network (run by Imperial College London), you’re seeing the gold standard of data. They have sensors everywhere. From the kerbside in Marylebone to the leafy outskirts of Hillingdon. The index usually scales from 1 to 10. A "1" means you’re basically in the Highlands. A "10" means you should probably stay inside and keep the windows shut.

Most days, London sits comfortably in the 1 to 3 range. That’s "Low."

But "Low" is a bit of a trick. The index is a composite. It looks at Nitrogen Dioxide ($NO_2$), Particulate Matter ($PM_{2.5}$ and $PM_{10}$), and Ozone ($O_3$). You might have a day where the $NO_2$ is spiked because of heavy traffic, but because the other pollutants are low, the overall "Daily Air Quality Index" (DAQI) still looks safe. Honestly, if you have asthma or hay fever, that composite score can be a total lie. You need to look at the individual pollutants.

Why $PM_{2.5}$ is the Real Villain

While everyone talks about $NO_2$ from diesel cars, the real health nightmare is $PM_{2.5}$. These are tiny particles, less than 2.5 micrometers in diameter. Think about a human hair. Now divide its width by thirty. That’s the size we’re talking about. These things are so small they don't just stay in your lungs; they cross into your bloodstream.

👉 See also: Why are US flags at half staff today and who actually makes that call?

In London, $PM_{2.5}$ doesn't always come from the car idling next to you. A huge chunk of it blows in from the continent, or comes from wood-burning stoves in posh living rooms in West London. It’s a regional problem, not just a local one. When we have "High" pollution days in the spring, it’s often because of a "perfect storm" of light winds, agricultural emissions from Europe, and our own local traffic.

The ULEZ Effect: Has It Actually Worked?

You can't talk about air quality in this city without mentioning the Ultra Low Emission Zone. It’s probably the most debated piece of local policy in a generation. But if we look strictly at the numbers—the hard, cold data—the impact on the air quality index London residents experience is undeniable.

According to the Mayor’s office and independent reports from City Hall, $NO_2$ concentrations in central London are nearly 50% lower than they would have been without the zone. That is massive. We’re talking about thousands of tonnes of pollutants simply not existing anymore.

- Roadside $NO_2$ levels have plummeted.

- The number of schools in areas exceeding legal limits has dropped from hundreds to nearly zero.

- Electric taxi fleets and "Green Bus Zones" have scrubbed the air in hotspots like Putney High Street.

However, critics and some scientists, like those contributing to the HEI (Health Effects Institute), point out that while $NO_2$ is down, $PM_{2.5}$ is a much harder beast to slay. Why? Because even electric cars have tires. Even electric cars have brakes. Every time a Tesla brakes, it releases "non-exhaust emissions" (NEE). As we transition away from fossil fuels, the "dust" from tires and brakes is becoming the dominant source of London’s particulate pollution.

Understanding the "Canyon Effect"

Ever noticed how some streets just feel... stuffy? That’s the street canyon effect. When you have tall buildings on both sides of a narrow road—think parts of the City or Holborn—the air can’t circulate. Pollutants get trapped at ground level. You could be standing 50 meters away in a park and breathe perfectly clean air, while the person on the main road is huffing 5x the legal limit of nitrogen dioxide.

This is why the general air quality index London reading for a borough like Westminster can be misleading. It’s an average. It doesn't tell you that the side of the street with the bus stop is twice as polluted as the side with the trees.

✨ Don't miss: Elecciones en Honduras 2025: ¿Quién va ganando realmente según los últimos datos?

How to Actually Use the Data (The Expert Way)

If you’re just checking the weather app on your iPhone, you’re getting a very basic, often delayed, version of the truth. If you actually care about your lungs, you need better tools.

- LondonAir.org.uk: This is the big one. Run by the Environmental Research Group at Imperial College. It’s the most accurate, real-time map available.

- AirText: You can sign up for text alerts. If the index is predicted to hit "Moderate" or "High," they’ll ping you. It’s a lifesaver for people with COPD or serious allergies.

- The Wind Direction: Sounds old-school, right? But if the wind is coming from the East, London is often breathing in the industrial output of Northern Europe. If it’s coming from the West (the Atlantic), we’re usually golden.

The Indoor Air Quality Paradox

Here is something nobody mentions: the air inside your London flat might be worse than the air on the street. London homes, especially the Victorian terraces, are either incredibly drafty or sealed up tight with modern double glazing.

When you cook on a gas stove, you're releasing $NO_2$ directly into your kitchen. If you light a scented candle or a wood burner, you’re spiking your internal $PM_{2.5}$ levels to "Very High" within minutes. On a day when the air quality index London map shows green, your living room could be a purple zone. Ventilation is everything.

Misconceptions That Need to Die

There's this idea that "leafy" London is always clean. Go to a wealthy area with lots of old houses and wood-burning stoves on a cold, still night in November. The $PM_{2.5}$ levels in those "leafy" streets can actually be higher than on a busy road in Hackney. Wood smoke is incredibly toxic and lingers low to the ground.

Another one? "Wearing a basic blue surgical mask protects you from pollution." It doesn't. Those masks are designed to stop droplets, not microscopic particles. If you’re serious about filtering out London’s air, you need an N95 or FFP3 rated mask that seals to your face. But honestly? Most people find them too uncomfortable for a daily commute.

What’s Next for London’s Air?

We are entering a new phase. The "easy" wins—like getting the oldest, dirtiest diesel trucks off the road—have mostly happened. The next decade will be a slog. It’s about tackling the "invisible" stuff.

🔗 Read more: Trump Approval Rating State Map: Why the Red-Blue Divide is Moving

The City of London has toyed with "Zero Emission Streets" where only EVs are allowed. There’s a massive push for "Low Traffic Neighborhoods" (LTNs), which are controversial as hell but do undeniably lower pollution on residential streets by forcing cars onto main arteries.

Then there’s the Thames. We often forget the river is a highway. The "Thames Strategy" is looking at how to clean up the emissions from tugs, clippers, and freight vessels which, for a long time, flew under the radar while we focused on cars.

Practical Steps for the Average Londoner

Stop checking the general city average. It’s useless. Instead, download the London Air app and look at the sensor closest to your house or office.

If you cycle, use the backstreets. Taking a parallel road just one block away from a main A-road can reduce your exposure to pollutants by up to 50%. It’s a literal life hack.

- Avoid walking on the "inside" of the pavement. Stay as far from the gutter as possible. Those few feet of distance from exhaust pipes actually make a measurable difference in what you inhale.

- Time your exercise. Pollution usually peaks during the morning and evening rush. If you can run at lunchtime or later in the evening, the air is generally thinner and cleaner.

- Invest in a HEPA filter. If you live near a major junction like the North Circular or Elephant and Castle, a high-quality air purifier isn't a luxury; it's a necessity for your bedroom.

- Ventilate smartly. Open windows at the back of the building, away from the street, to get a cross-breeze without the soot.

London’s air isn't the "pea-souper" fog of the 1950s that killed thousands. It’s much more subtle now. It’s a long-term game of marginal gains. By paying attention to the specific data points of the air quality index London provides, you can navigate the city without treating your lungs like a filter.

Monitor the "Nowcast" maps on the London Air website during heatwaves. High temperatures trigger ground-level ozone formation, which is a massive respiratory irritant that often goes ignored compared to traffic fumes. If you see ozone levels climbing on a hot July afternoon, that is the time to skip the outdoor HIIT workout and head to an air-conditioned gym instead.

Living in a global mega-city means accepting some level of environmental trade-off, but being "air-literate" is the best way to tilt the scales back in your favor. Check the sensors, choose the side streets, and keep the air moving in your home. That is how you actually handle London's atmosphere in 2026.