Honestly, the dream was incredible. A nuclear fusion reactor the size of a shipping container, capable of powering a city of 100,000 people or keeping a C-5 Galaxy in the air for years without refueling. When Lockheed Martin’s Skunk Works first went public with their lockheed martin compact fusion project back in 2014, the world basically stopped for a second. We weren't talking about the massive, multi-billion dollar ITER project in France that’s the size of a football stadium. We were talking about a truck-sized "magnetic bottle" that would change everything.

But it's 2026 now. The hype has cooled.

If you search for the latest updates today, you’ll find a lot of silence where there used to be bold press releases. People still ask: "Where is my backyard fusion?" The reality is a lot more complicated than a sleek promotional video. It’s a mix of brilliant physics, crushing engineering hurdles, and the brutal reality of how the defense industry handles "high-risk, high-reward" experiments.

The Secret Sauce: Why It Was Supposed to Work

Most fusion projects use a "Tokamak" design. Imagine a giant donut. You spin plasma around in circles using magnets until it gets hot enough to fuse. It's stable, but it has to be huge to work. Lockheed Martin took a different path. They went with a "high-beta" concept.

Basically, they wanted to use the magnetic field much more efficiently. In a Tokamak, the magnetic pressure is much higher than the plasma pressure. In the Skunk Works design—led by Dr. Thomas McGuire—the goal was a 1:1 ratio.

👉 See also: Finding the 24/7 apple support number: What You Need to Know Before Calling

Small is Fast?

The logic was simple. If the reactor is small, you can iterate faster. Instead of waiting five years to design and build a single test, you could do it in months. They moved through versions like T4 and T4B at a lightning pace. This "fail fast" mentality is what Skunk Works is famous for. They wanted to shrink the timeline from decades to years.

What Actually Happened with the T4 Experiments

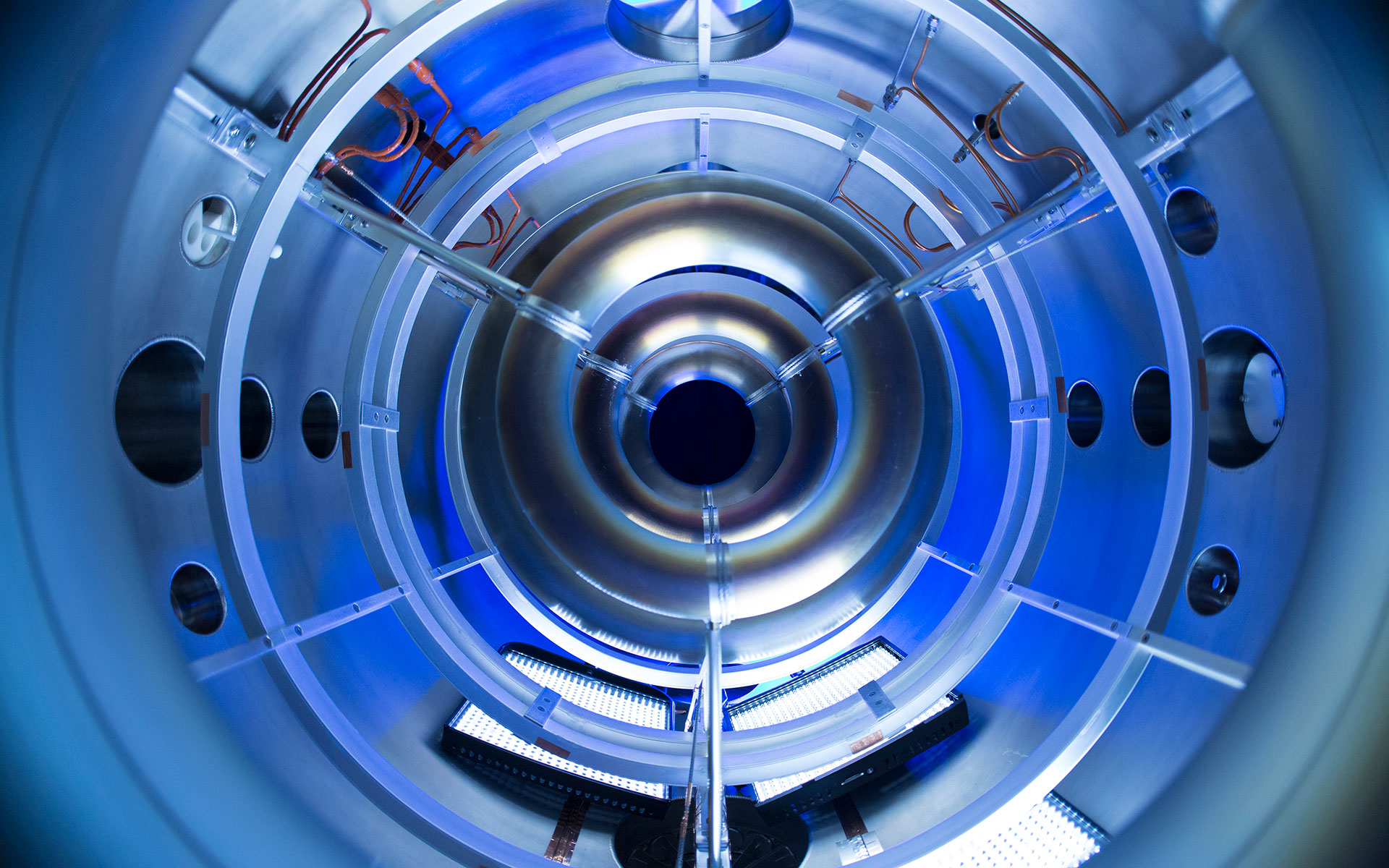

Around 2017 and 2018, things seemed to be moving. Lockheed actually secured a patent (US9959942B2) for their magnetic confinement system. This wasn't just some PowerPoint dream. They had a physical vacuum chamber and superconducting coils.

The problem? Physics is a stubborn beast.

When you make a fusion reactor small, you run into a nightmare of "heat confinement." Critics like Steven Cowley, a heavyweight in plasma physics, pointed out a fundamental rule: when you double the size of a machine, you get eight times better heat confinement. By going small, Lockheed was fighting an uphill battle against thermodynamics. The heat just kept leaking out of the "magnetic bottle" before the plasma could reach the hundreds of millions of degrees needed for sustained fusion.

✨ Don't miss: The MOAB Explained: What Most People Get Wrong About the Mother of All Bombs

The Quiet Pivot and Current Status

By 2021, the loud announcements stopped. While the company never officially "cancelled" the project in a dramatic bonfire, evidence suggests the Skunk Works team has shifted focus. Reports indicate the dedicated division was largely folded or the effort was significantly scaled back.

Does that mean it was a failure? Not necessarily.

In the world of aerospace and defense, these "dark" projects often go back into the shadows once they hit a certain stage. They might have hit a wall that requires new materials science—stuff that doesn't exist yet. Or, they might have found a specific niche application that is now classified. But for the "power the world for free" crowd, the silence is deafening.

The New Players Stealing the Spotlight

While Lockheed went quiet, others stepped into the gap. You’ve probably heard of Commonwealth Fusion Systems (CFS) or TAE Technologies. They are using different tricks—like High-Temperature Superconductors (HTS)—to keep their reactors relatively small without losing all that precious heat.

🔗 Read more: What Was Invented By Benjamin Franklin: The Truth About His Weirdest Gadgets

- Commonwealth Fusion Systems: They’re aiming for net energy gain with their SPARC reactor by the end of 2026.

- Helion Energy: They have a deal with Microsoft to provide fusion power by 2028. Yes, an actual contract with a delivery date.

- TAE Technologies: Working on a beam-driven fusion approach that’s less about "bottles" and more about colliding rings of plasma.

Why the Lockheed Martin Compact Fusion Concept Still Matters

Even if we don't have a Lockheed-branded reactor in our trucks today, the project changed the conversation. It proved that private capital and "fast" engineering could compete with international government projects. It forced the old guard to look at high-beta designs again.

Honestly, the biggest legacy of the Skunk Works attempt might be the "Compact" part of the name. Before 2014, "compact fusion" was mostly seen as sci-fi or fringe science. Today, it’s a multi-billion dollar industry.

Practical Insights for 2026

If you’re following this space, don't wait for a Lockheed press release. The action has moved.

- Watch the Magnets: The real breakthrough isn't the "shape" of the reactor; it's the strength of the magnets. Keep an eye on REBCO (Rare-Earth Barium Copper Oxide) superconducting tapes. That’s what’s making "compact" possible now.

- Follow the Startups: The agility Lockheed touted is now being lived out by companies like CFS, Helion, and Zap Energy. They are the ones actually firing up reactors this year.

- Check the Patents: Lockheed still holds those patents. If they solve the heat loss issue in secret, they still own the keys to the kingdom.

The dream of a truck-sized sun isn't dead. It just isn't as easy as the brochures made it look. Fusion is the ultimate engineering "boss fight," and even the geniuses at Skunk Works found out that sometimes, you need a bigger hammer—or in this case, a bigger magnet.

To stay ahead of the curve, keep your eyes on the SPARC test results coming out of MIT/CFS later this year. Those results will tell us once and for all if the "small" approach can actually generate more power than it consumes. If they succeed, the Lockheed vision will finally have its proof of concept, even if the name on the side of the box is different.