You’ve seen the photos. On one side, a pristine desert or a rugged mountain range. On the other, a geometric patchwork of neon-blue and acid-yellow ponds that look like they belong on another planet.

It’s jarring.

People love their iPhones and their Teslas, but they kinda hate seeing where the "juice" actually comes from. When we talk about lithium mines before and after, we’re really talking about a massive, high-stakes trade-off that the world hasn’t quite figured out how to balance yet. We want the green future, but the "before" is often a fragile ecosystem, and the "after" is an industrial scar that lasts for decades.

Honestly, the transition isn't as clean as the marketing brochures make it look.

What a Lithium Mine Actually Looks Like Before Anything Starts

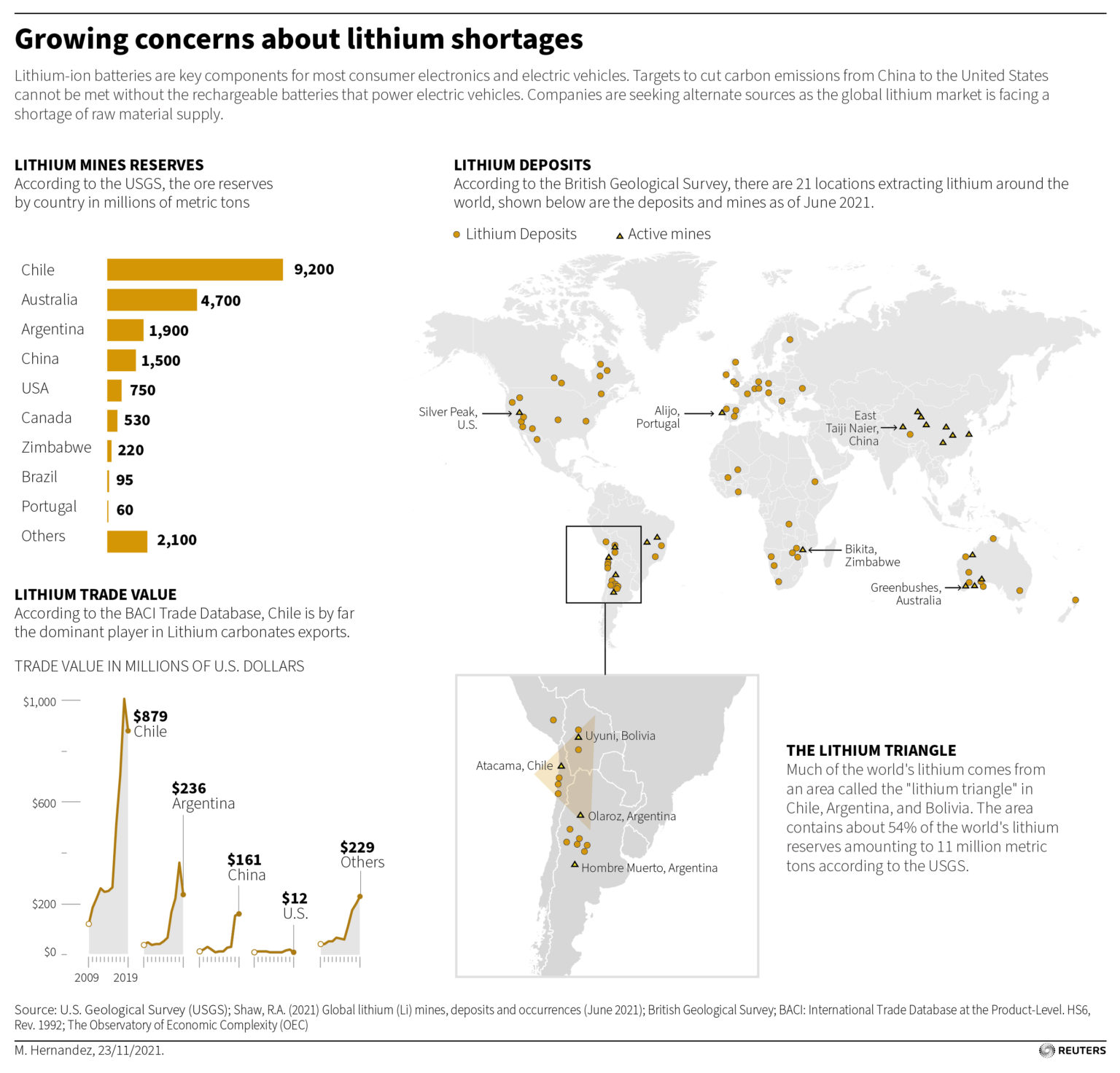

Before the drills arrive, most lithium-rich sites are remarkably quiet. Take the "Lithium Triangle" in South America—spanning parts of Chile, Argentina, and Bolivia. Before the pumps go in, places like the Salar de Atacama are vast, blindingly white salt flats. It’s an arid, Martian landscape where the silence is heavy.

There isn't much visible life, but that’s a bit of a trick.

Underground, there’s a complex hydrological system. Microorganisms, unique brine-shrimp, and migratory birds like the Andean flamingo depend on specific water levels in the lagoons surrounding these flats. In places like Thacker Pass in Nevada, the "before" is a sagebrush sea. It’s home to pronghorn antelope, golden eagles, and deep cultural history for the Fort McDermitt Paiute and Shoshone Tribes. It looks like "nothing" to an investor in a boardroom, but it's a functioning, delicate carbon sink.

The Transformation: Moving From "Nothing" to Infrastructure

When the mining begins, the visual shift is immediate and permanent.

🔗 Read more: Apple MagSafe Charger 2m: Is the Extra Length Actually Worth the Price?

In hard-rock mining—like what you see in Greenbushes, Western Australia—the "after" involves massive open pits. We’re talking about blasting through granite to get at spodumene ore. It’s traditional mining. Dust. Heavy machinery. Massive tailings piles.

But the brine extraction in South America is what really messes with people's heads.

To get the lithium, companies pump massive amounts of salty water (brine) from beneath the salt flats into giant surface ponds. Then, they just let the sun do the work. Over 12 to 18 months, the water evaporates, leaving behind a concentrated lithium soup. This is where the lithium mines before and after contrast is the wildest. You go from a flat, white expanse to these vibrant, chemical-looking pools that can be seen from space.

It’s a slow-motion industrial process.

The Water Problem Everyone Is Arguing About

Water is the sticking point. It always is.

In the Salar de Atacama, it takes roughly 500,000 gallons of water to produce one ton of lithium. Think about that. In one of the driest places on Earth, mining companies are sucking up millions of gallons of brine. While the companies argue that brine isn't "fresh water" and therefore doesn't matter, local farmers in places like Toconao disagree. They’ve seen their meadows dry up. They’ve seen the carob trees die.

The "after" of a lithium mine isn't just the hole in the ground; it's the altered water table miles away from the site.

💡 You might also like: Dyson V8 Absolute Explained: Why People Still Buy This "Old" Vacuum in 2026

Research from the University of Arizona and other institutions has suggested that brine pumping can cause fresh water to migrate toward the salty vacuum left behind, effectively "contaminating" or depleting the local drinking and irrigation sources. It’s a subterranean tug-of-war.

Why Hard Rock Is Different (But Not Necessarily "Better")

Hard rock mining, like the projects in North Carolina or Australia, doesn't use the evaporation method. It’s faster. You dig it up, you crush it, you process it.

- Pros: Smaller water footprint compared to brine evaporation.

- Cons: Massive carbon footprint because you’re running heavy equipment and high-heat kilns.

- The Look: It looks like a standard quarry, which is arguably "uglier" to the naked eye than the colorful ponds of Chile.

The Social "After": Boomtowns and Broken Promises

The "after" isn't just environmental. It’s socioeconomic.

When a mine opens, money floods in. For a town like Silver Peak, Nevada—which has been home to the only operating lithium mine in the U.S. for decades—the mine is the lifeblood. It provides jobs that pay way better than retail or ranching. But this comes with a "resource curse" risk.

In some South American communities, the "after" has meant fractured social ties. Some families get jobs at the mine and move into modern housing; others, who rely on traditional llama herding, find their grazing lands ruined and their culture sidelined.

It's messy. It’s rarely a win-win.

Can We Fix the "After"?

There is hope in new tech, specifically Direct Lithium Extraction (DLE).

📖 Related: Uncle Bob Clean Architecture: Why Your Project Is Probably a Mess (And How to Fix It)

Companies like Lilac Solutions are trying to bypass the giant evaporation ponds entirely. The idea is to pump the brine, grab the lithium using beads or solvents, and then pump the "used" water right back underground. If it works at scale, the lithium mines before and after comparison would look much less dramatic. You’d have a small processing plant instead of 10 square miles of neon ponds.

But DLE is still "the next big thing" that hasn't quite hit its stride in terms of global production volume.

The Reality of Reclamation

Eventually, the mine closes. What then?

Mining laws in the U.S. and Australia require "reclamation." This means the company has to try to put the land back the way they found it—or at least make it safe and green again. They fill in holes, cap tailings, and plant native grasses.

But you can't really "un-pump" an aquifer.

You can’t put a mountain back together once it’s been turned into gravel and shipped to a battery plant in China. The "after" of a lithium mine is a permanent change to the geography. We are essentially trading local landscapes for a global climate benefit. Whether that’s a fair trade depends entirely on who you ask.

Actionable Insights for the Conscious Consumer

If you're looking at the impact of your own tech habits, here is what actually matters right now:

- Check the Source: Look for companies that source lithium from IRMA-certified (Initiative for Responsible Mining Assurance) mines. This standard is one of the toughest for tracking environmental and social "after" effects.

- Support Battery Recycling: The best way to avoid a "before and after" mine scenario is to use the lithium we already have. Companies like Redwood Materials are getting incredibly good at recovering 95% of lithium from old batteries.

- Acknowledge the Trade-off: Understand that "zero emissions" at the tailpipe doesn't mean "zero impact" at the source. Being a knowledgeable advocate means pushing for better mining tech, like DLE, rather than just pretending the mines don't exist.

- Watch the "Lithium Valley": Keep an eye on the Salton Sea projects in California. If they can successfully extract lithium from geothermal brine, it could provide a blueprint for the least-invasive "after" in the history of the industry.