Franz Liszt was the original rock star. Long before Jagger or Hendrix, Liszt was shattering pianos and making Victorian audiences faint from sheer sensory overload. But while his technical wizardry is legendary, his Liszt Piano Concerto No. 1 in E-flat major represents something much deeper than just showing off. It’s a tight, aggressive, and revolutionary piece of music that actually took him twenty-six years to get right. Honestly, it’s kinda miraculous it sounds as cohesive as it does.

You’ve probably heard the opening theme. It’s bold. It’s loud. It’s basically a musical dare.

Most people think Liszt just sat down and scribbled out these massive chords in a fit of inspiration. Not even close. He started the first sketches in 1830 when he was just nineteen. He didn't actually premiere the thing until 1855 in Weimar, with Hector Berlioz on the podium. Think about that timeline. He lived with these melodies for over two decades, refining them, tweaking the orchestration, and making sure the piano didn't just accompany the orchestra but fought it—and won.

The Triangle "Scandal" and Structural Genius

One of the weirdest things about the Liszt Piano Concerto No. 1 is the triangle. Seriously. In the third movement, the Allegretto vivace, Liszt brings in the triangle for a playful, percussive texture. Today, we don't blink an eye. In the 1850s? It was a scandal.

The critic Eduard Hanslick—who was basically the final boss of conservative music criticism—hated it. He famously dubbed it the "Triangle Concerto" as a way to mock Liszt’s supposed lack of seriousness. Hanslick thought the inclusion of such a "lowly" instrument in a formal concerto was a joke. But Liszt knew exactly what he was doing. He wanted a specific, metallic clarity to cut through the piano’s resonance.

Structure-wise, this concerto is a bit of a rebel. Most concertos of that era followed the strict three-movement "fast-slow-fast" rule with clear breaks between them. Liszt threw that out the window. He used what musicologists call "thematic transformation."

Basically, he takes one or two main ideas and twists them, stretches them, and turns them inside out across four distinct but connected sections played without a break. It's like a 20-minute rollercoaster where the tracks keep shifting under you.

✨ Don't miss: Bob Hearts Abishola Season 4 Explained: The Move That Changed Everything

Why the E-flat Major Key Matters

Liszt didn't pick keys by accident. E-flat major is traditionally heroic. Think of Beethoven’s Eroica Symphony. By choosing this key for the Liszt Piano Concerto No. 1, he was staking a claim. He was telling the world, "I am the successor to the giants."

The opening motif—G-E-flat-F-B-flat—is often sung by musicians with the snarky lyrics, "Das versteht ihr alle nicht" (None of you understand this). It's a bit of an inside joke in music school, but it captures the defiant spirit of the piece.

A Technical Nightmare for the Performer

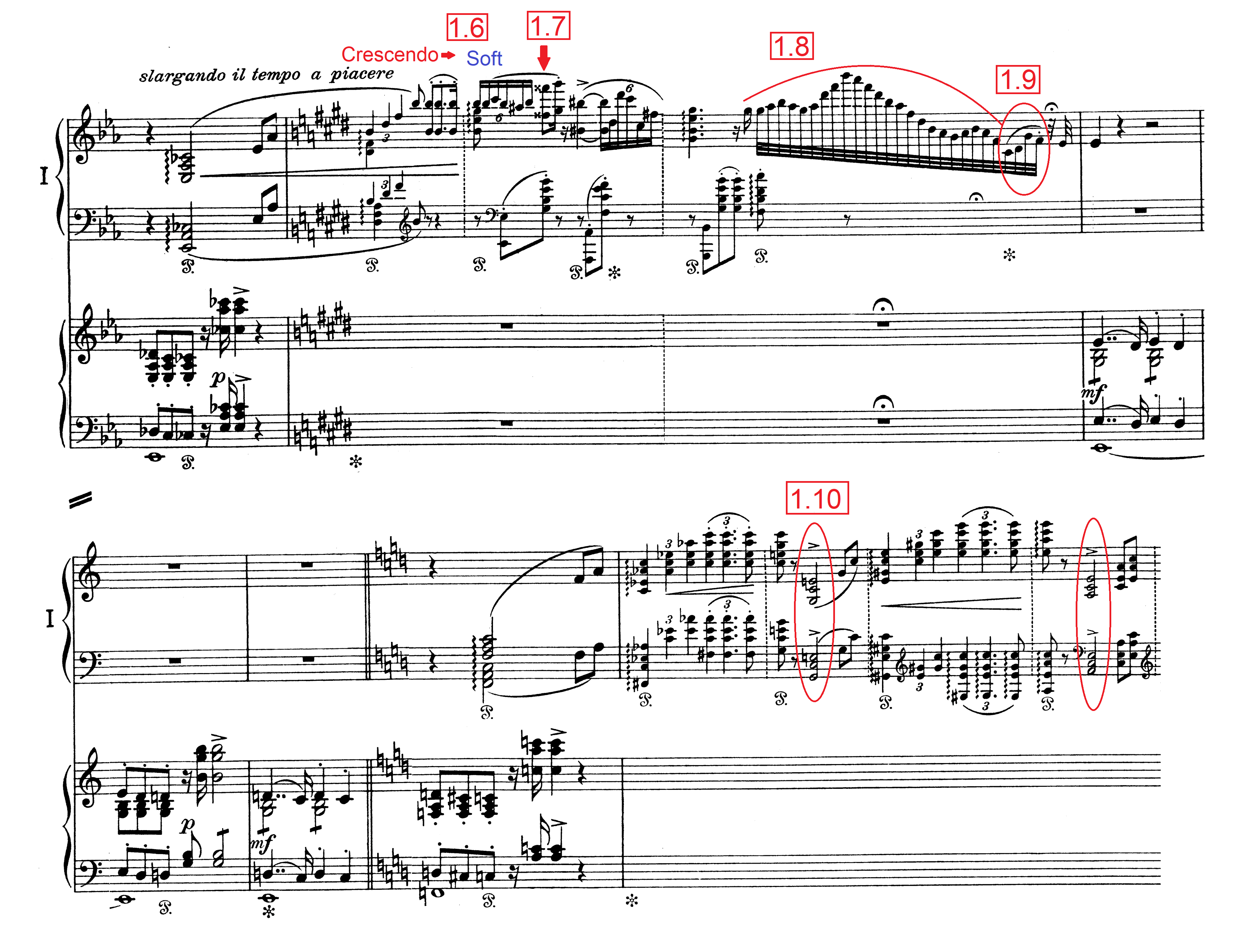

If you want to play this, you need hands like iron and the soul of a poet. It's not just about playing fast. Anyone can practice scales. The difficulty in the Liszt Piano Concerto No. 1 lies in the rapid-fire octaves and the "blind" leaps.

Look at the second movement, the Quasi adagio. It starts as a beautiful, operatic nocturne. The piano sings. But then, it transitions into this shimmering, delicate cadenza that requires incredible finger independence. You’re playing these light, fluttering notes while maintaining a deep, resonant melody. It’s exhausting.

- The double-note passages require terrifying precision.

- The finale demands "martellato" (hammered) technique that can leave a pianist’s forearms screaming.

- The interplay with the woodwinds is chamber-music-level tight.

I’ve seen world-class soloists break a sweat five minutes into this. It’s compact. Because it’s only about 18 to 20 minutes long, there is no "fluff." There is nowhere to hide. If you miss a note in the big chromatic runs, everyone knows.

The Weimar Premiere and the Berlioz Connection

The 1855 premiere was a turning point for Liszt. By this time, he had mostly retired from the touring virtuoso life to focus on composing and conducting in Weimar. Having Berlioz conduct was a massive power move. These two were the vanguards of the "New German School."

🔗 Read more: Black Bear by Andrew Belle: Why This Song Still Hits So Hard

They wanted music to be programmatic, emotional, and structurally fluid. The Liszt Piano Concerto No. 1 was their manifesto. It proved that a concerto could be a "symphonic poem" with a soloist. It wasn't just a vehicle for a star performer; it was a serious piece of architectural art.

Common Misconceptions About the Piece

Some people call this "shallow" music. They say Liszt is all flash and no substance. Honestly, they’re wrong.

If you look at the score, the way Liszt weaves the cello solos in the second movement with the piano's response is incredibly sophisticated. It’s intimate. It’s vulnerable. Yes, the ending is a bombastic firework show, but you have to earn that ending through the psychological shifts of the earlier sections.

Another myth is that it’s "easy" compared to his Second Concerto or the Totentanz. While the Second Concerto is more harmonically experimental, the First is a tighter "trap." The tempo shifts are sudden. If the conductor and the pianist aren't breathing together, the whole thing falls apart in the third movement when the triangle starts ticking.

How to Actually Listen to it (The Expert Way)

Don't just put it on as background music. You’ll miss the best parts. To really appreciate the Liszt Piano Concerto No. 1, you have to track the "fate" motif from the first few seconds.

- The Introduction: Listen to the strings. They are aggressive. The piano answers with massive, declamatory chords. This is the "hero" entering the arena.

- The Lyrical Shift: About five minutes in, everything gets quiet. This is the "soul" of the piece. Pay attention to how the piano imitates a singer.

- The Triangle Entry: When you hear that ting, notice how the piano's character changes. It becomes cheeky, almost like a jester.

- The Grand Transformation: By the end, that scary opening theme from the beginning comes back, but now it’s triumphant and fast. It’s the same DNA, just a different mood.

The Best Recordings to Hunt Down

If you want to hear this done right, you have to be picky. Martha Argerich’s recording with Claudio Abbado is basically the gold standard. Her speed is legendary, but she also finds the "ghosts" in the music. It’s haunting.

💡 You might also like: Billie Eilish Therefore I Am Explained: The Philosophy Behind the Mall Raid

Sviatoslav Richter is another must-listen. His approach is more structural and powerful. He treats the piano like an entire orchestra. Then there’s Lang Lang, who brings a lot of the "Liszt-as-superstar" energy back to the piece, which is divisive but definitely entertaining.

Actionable Insights for Classical Fans

If you're a student or just a dedicated listener, here is how to level up your understanding of this work:

For the Aspiring Pianist:

Focus on the "arm weight" in the opening chords. If you try to play them with just your fingers, you’ll sound thin and harsh. Use your whole body. For the Allegretto, practice your leaps without looking at the keys to build that "spatial memory."

For the Serious Listener:

Find a "study score" (Boosey & Hawkes makes a good one). Even if you don't read music well, following the visual rise and fall of the notes during the finale will show you how Liszt layered the instruments to create that massive wall of sound.

For the History Buff:

Read Liszt’s letters from the Weimar period. He was dealing with a lot of professional jealousy at the time, and you can hear that "chip on the shoulder" in the music. It’s a work of someone who knew they were being judged and decided to be even louder.

The Liszt Piano Concerto No. 1 isn't just a relic of the 19th century. It’s a blueprint for the modern virtuoso. It’s short, punchy, and incredibly difficult to pull off with actual class. Next time you hear it, ignore the "flashiness" for a second and listen to the way the themes evolve. It’s a masterclass in musical economy hidden inside a spectacle.