You know that feeling when a song is so baked into your DNA that you forget someone actually had to sit down and write it? That’s "Do-Re-Mi." Most of us learned it in kindergarten. We sing it to our kids. It’s basically the "Alphabet Song" of musical theater. But when you sit down to listen to Richard Rodgers Do Re Mi, you aren't just hearing a nursery rhyme. You’re hearing a genius at the absolute peak of his powers trying to solve a very specific narrative problem.

Richard Rodgers was a dramatist who happened to communicate through melody. By the time The Sound of Music opened at the Lunt-Fontanne Theatre in 1959, he and Oscar Hammerstein II had already changed the world with Oklahoma! and South Pacific. They weren't just writing "tunes." They were writing character arcs. "Do-Re-Mi" is the moment Maria transforms from a chaotic governess into a teacher. It’s the pivot point of the whole show. Without this song, the kids don't trust her, and the Captain doesn't fall for her. It’s the engine.

The Mathematical Brilliance of Simplicity

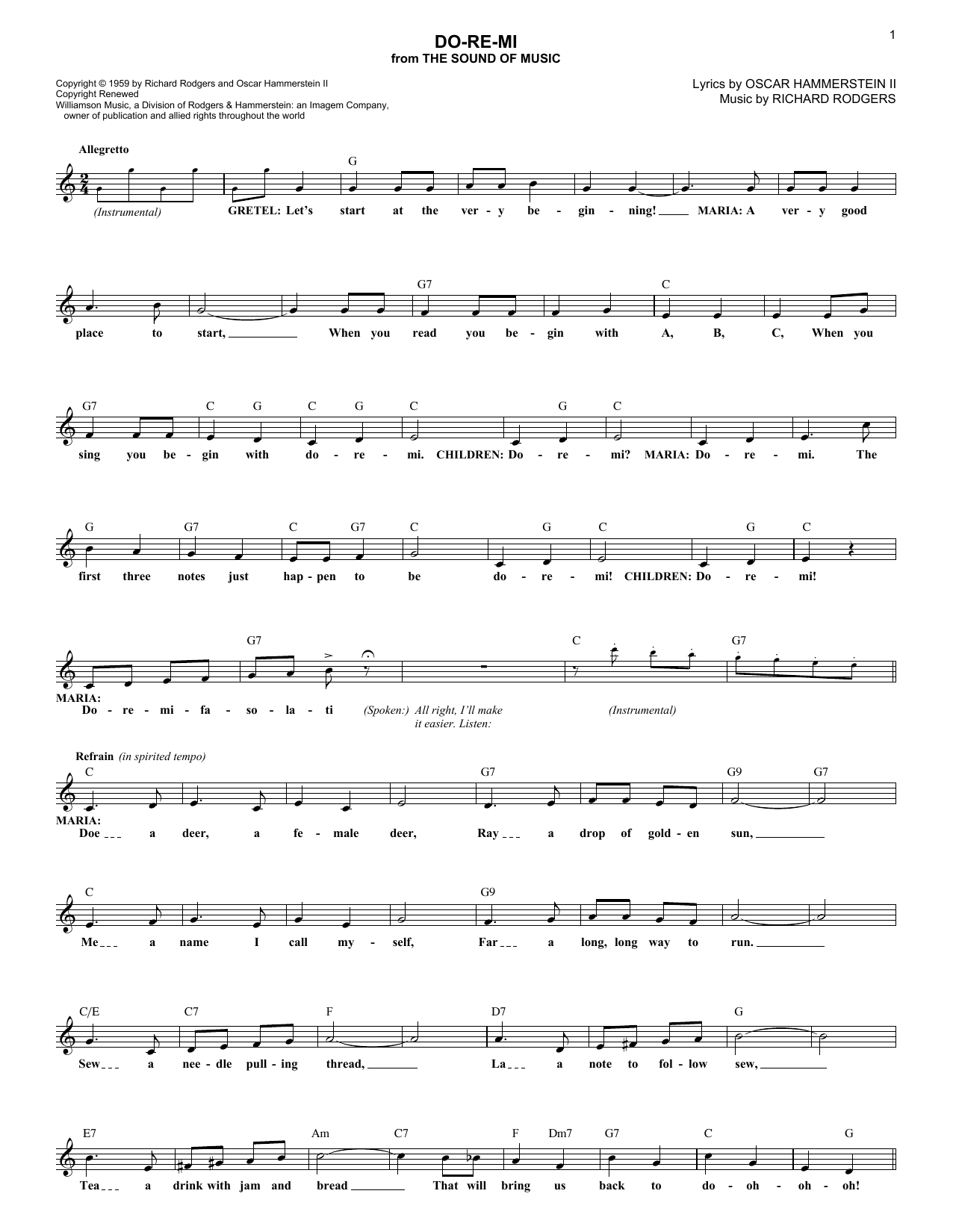

It’s actually kinda wild how hard it is to write something this simple. Rodgers had to create a song that teaches music while being music. If you analyze the score, you see he’s doing something clever. He starts with a basic C major scale. Most composers would make that boring. Rodgers makes it a conversation.

The song functions as a "pedagogical" number. That's a fancy way of saying it’s a teaching tool. Every note corresponds to a mnemonic. "Doe, a deer, a female deer." It’s literal. It’s accessible. But then, Rodgers starts layering. Listen to the mid-section where the kids start singing the notes in counterpoint. Suddenly, it’s not just a scale; it’s a complex arrangement. He’s showing, not telling, how music builds from a single block into a cathedral of sound.

Why the Original 1959 Cast Recording Hits Different

People usually go straight to the 1965 movie soundtrack with Julie Andrews. I get it. Her voice is like crystal. It’s perfect. But if you want to really understand Rodgers’ intent, find the 1959 original Broadway cast recording starring Mary Martin.

📖 Related: Why Grand Funk’s Bad Time is Secretly the Best Pop Song of the 1970s

Martin’s voice had a different texture—a bit more "earthy" and theatrical. In that version, the interplay between the guitar (which Maria is supposed to be playing) and the orchestration feels more intimate. Rodgers was known for being a bit of a stickler for his arrangements. He didn't want fluff. He wanted the melody to drive the emotion. When you listen to Richard Rodgers Do Re Mi through the lens of the stage production, you realize it was designed to be staged with movement that mirrors the rising pitch of the scale. It’s a physicalization of joy.

The Hammerstein Connection

We can't talk about Rodgers without Hammerstein. Oscar was struggling with cancer while writing these lyrics. He knew this would likely be their last show. There’s a poignancy in the lyrics of "Do-Re-Mi" that people miss because they think it’s just for kids. "When you know the notes to sing, you can sing most anything."

That’s a manifesto.

It’s about empowerment. It’s about giving the Von Trapp children—who were living under a literal regime of silence and whistles—their voices back. Hammerstein’s lyrics are deceptively simple, but they provide the structure that allows Rodgers’ melody to soar. They were a "words-first" team, usually. Hammerstein would send a lyric, and Rodgers would set it to music in a matter of hours. This one, however, took precision. It had to be grammatically and musically "correct" to function as a lesson.

👉 See also: Why La Mera Mera Radio is Actually Dominating Local Airwaves Right Now

The Legacy of the Solfège

Rodgers didn't invent "Do, Re, Mi." That’s been around since Guido of Arezzo in the 11th century. But Rodgers popularized it for the Western world in a way no textbook ever could.

- He turned a music theory lesson into a pop hit.

- He utilized the "major scale" to create a sense of safety and home.

- He proved that sophistication doesn't require complexity.

Honestly, most modern songwriters couldn't do this. We live in an era of "vibes" and "textures." Rodgers lived in the era of architecture. If one note was out of place, the whole thing collapsed. When you listen to Richard Rodgers Do Re Mi, pay attention to the "Soh." It’s the dominant note. It pulls you back to "Do." It’s like a rubber band. That tension and release is why the song is addictive.

Beyond the Movie: The Rare Versions

If you’re a deep-diver, you should look for the 1973 London revival or even the televised versions from the early 2000s. You’ll notice how different directors interpret Rodgers’ "bridge" in the song. Some make it a frantic dance; others keep it focused on the vocal harmony.

There’s also the 1960 album The Unsinkable Molly Brown era where jazz musicians started covering Rodgers’ tunes. Hearing a jazz quartet take on "Do-Re-Mi" is a trip. It reveals the "bones" of the song. You realize that even without the lyrics, the melodic progression is incredibly sturdy. It survives being flipped, swung, and syncopated because the underlying structure is flawless.

✨ Don't miss: Why Love Island Season 7 Episode 23 Still Feels Like a Fever Dream

Common Misconceptions About the Song

A lot of people think "Do-Re-Mi" was an old folk song that Rodgers just arranged. Nope. He wrote every note of that melody.

Another big one? That it’s "easy" to sing. Try singing the fast-paced "syllable scramble" at the end without tripping over your tongue. It requires incredible breath control. Rodgers often wrote for "actor-singers," meaning he valued clarity of diction as much as tone. He wanted every "Tea, a drink with jam and bread" to be crisp.

Practical Ways to Appreciate the Work

If you really want to get the most out of this, don't just play it on your phone speakers.

- Use high-quality headphones: Listen for the woodwinds in the background. Rodgers loved using flutes and oboes to "color" the children’s voices.

- Watch the 1965 film but mute it: Look at the choreography. See how the kids move up and down steps as the notes go up and down the scale. It’s a visual representation of Rodgers’ score.

- Compare the "Playoff": Listen to how the song ends in the stage version versus the film. The "big finish" is a classic Rodgers trope—the "button" at the end of the scene that tells the audience exactly when to clap.

Next Steps for the Musical Enthusiast

To truly understand the genius of this piece, your next move should be comparing it to Rodgers’ earlier work with Lorenz Hart. Listen to something like "Mountain Greenery." You’ll hear a younger, more frantic Rodgers. Then, come back and listen to Richard Rodgers Do Re Mi. You’ll see the evolution of a man who stopped trying to prove how clever he was and started writing music that felt like it had always existed.

Check out the Library of Congress archives online if you want to see the original lead sheets. Seeing Rodgers' handwriting—how clean and decisive his notation was—tells you everything you need to know about the man. He knew exactly what he was doing.

Go find a copy of the 40th Anniversary Soundtrack or the newer live-television cast recordings. Notice how the orchestration has changed over the decades, yet that central C-major scale remains untouched and immovable. It’s the closest thing we have to a perfect musical cell. Keep your ears open for the "inner voices" in the harmony; that’s where the real Richard Rodgers is hiding.