Mike Shinoda once hated it. Let that sink in for a second. The man who basically architected the backbone of the song didn't even want it on the album. He fought against it. He thought it was too poppy, too accessible, maybe even a little too "soft" compared to the jagged edges of Papercut or One Step Closer. But here we are, decades later, and Linkin Park In the End remains the definitive anthem of a generation that felt like they were screaming into a void. It’s the song that redefined what nu-metal could be and, honestly, what it shouldn't have been.

It’s weird.

Usually, when a band reaches this level of ubiquity, the song starts to feel like a parody of itself. You hear it at sporting events, in grocery stores, and in those early 2000s AMV (Anime Music Video) tributes that basically built the foundation of YouTube. Yet, there’s something about that four-note piano riff—D#, A#, B, F—that still hits like a ton of bricks. It’s lonely. It’s cold.

Why Linkin Park In the End Almost Never Happened

The recording sessions for Hybrid Theory were notorious for being a push-and-pull between the band’s vision and the pressures of a label that didn't quite get them. Don Gilmore, the producer, was known for being incredibly demanding. He’d make Chester Bennington sing the same line for hours until his voice was raw. But the real tension with Linkin Park In the End was internal.

Shinoda wrote the demo in a rehearsal studio on Hollywood and Vine. He stayed up all night. He was trying to find a way to marry hip-hop sensibilities with the brooding atmosphere of the rock scene they were emerging from. When he played it for the rest of the guys, the reaction wasn't a unanimous "this is a hit." In fact, Chester Bennington famously stated in several interviews later in his life that he didn't even like the song at first. He didn't want it to be a single. He thought the fans would hate it.

Imagine being the guy who almost vetoed the song that would eventually reach over 1.7 billion views on YouTube. It’s wild.

The song works because of the duality. You have Mike’s steady, rhythmic rapping representing the logical, analytical side of a failing relationship or situation. Then Chester bursts in with that melodic, soaring chorus that feels like an emotional breakdown. It’s the sound of someone realizing that effort doesn't always equal success. You can try so hard and get so far, but the universe doesn't owe you anything. That realization is the core of the Linkin Park In the End legacy.

👉 See also: The Real Story Behind I Can Do Bad All by Myself: From Stage to Screen

The Piano Hook and the Anatomy of a Hit

What’s the first thing you hear? It isn't a guitar. It isn't a drum beat. It’s that haunting piano. In an era where Limp Bizkit was dominating with "Nookie" and Slipknot was scaring parents everywhere, Linkin Park chose to start their biggest hit with a minimalist piano melody. It was a massive risk.

Musicologists have actually looked at why this specific melody works. It’s repetitive but unresolved. It creates a sense of anxiety. When the drums finally kick in—that crisp, hip-hop-influenced beat—the tension releases just enough to keep you hooked. The song doesn't use a traditional guitar solo. It doesn't need one. Brad Delson’s guitar work is atmospheric, serving the song rather than the ego.

- The song was recorded at NRG Recording Studios in North Hollywood.

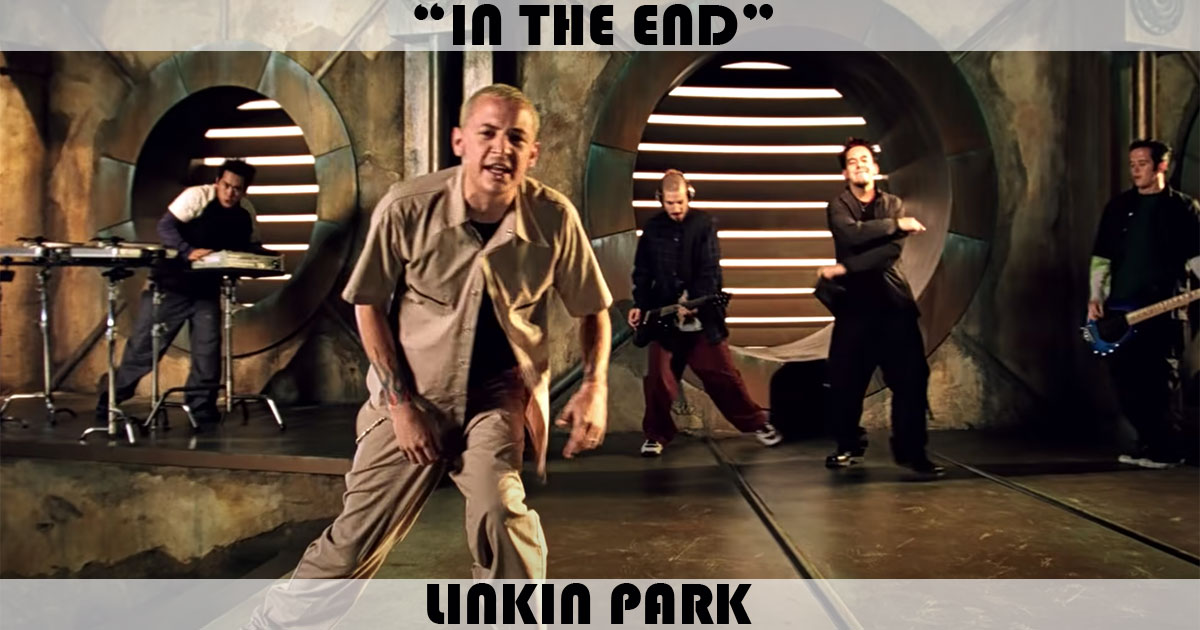

- The music video was filmed during a break on the Ozzfest tour.

- It reached number 2 on the Billboard Hot 100, which is insane for a "heavy" band in 2002.

It’s also worth noting the bridge. "One thing, I don't know why..." The way the music drops out and then builds back up with those layered vocals? That’s pure songwriting craft. It’s not just noise. It’s architecture.

The Cultural Impact: More Than Just a Meme

We have to talk about the internet. You can't talk about Linkin Park In the End without talking about how it became the soundtrack to the early 2000s web. Whether it was Naruto fights or Dragon Ball Z clips, this song was the backdrop. It became a shorthand for "angst," but in a way that felt authentic rather than manufactured.

But there’s a deeper layer.

In 2017, after Chester Bennington passed away, the song took on a haunting new meaning. Suddenly, lyrics like "I had to fall to lose it all" didn't just sound like a breakup song. They sounded like a window into a struggle that was much more permanent. Fans started listening to the lyrics with a different lens. They weren't just singing along anymore; they were grieving.

✨ Don't miss: Love Island UK Who Is Still Together: The Reality of Romance After the Villa

The song’s ability to pivot from a radio hit to a funeral dirge to a motivational anthem is why it stays relevant. It’s a shapeshifter. It fits whatever pain you’re carrying. Honestly, if you look at the streaming numbers, it hasn't slowed down. It’s one of the few songs from that era that hasn't been "dated" by its production. It still sounds heavy. It still sounds clean.

What Most People Get Wrong About the Lyrics

A lot of people think the song is strictly about a romantic breakup. It’s the easiest interpretation. "I put my trust in you, pushed as far as I can go." But if you listen to Mike Shinoda talk about his writing process during that era, it was often about the struggle of the band itself.

They were trying to make it in an industry that wanted them to be something they weren't. They were dealing with critics who called them a "boy band with guitars." The "you" in the song could easily be the music industry, or a friend who let them down, or even a version of themselves they were trying to leave behind.

The ambiguity is the genius.

If it were too specific, we wouldn't still be talking about it. By keeping the lyrics focused on the feeling of failure rather than the cause of it, they created a universal template. Everyone has felt like they gave 110% to something only to watch it crumble.

Technical Mastery in the Studio

The production on Linkin Park In the End is a masterclass in "less is more." If you isolate the tracks, you'll notice how much space there is. The bassline isn't doing anything flashy; it’s just holding the floor. The scratches from Joe Hahn aren't overbearing; they add texture.

🔗 Read more: Gwendoline Butler Dead in a Row: Why This 1957 Mystery Still Packs a Punch

Linkin Park was one of the first bands to really use the studio as an instrument in the way a hip-hop producer does. They weren't just four guys in a room playing live. They were layering, sampling, and refining. The contrast between the verse and the chorus is achieved not just by volume, but by the frequency range. The verses are narrow and focused. The choruses are wide and massive.

- The Rap Verses: Mike's delivery is deliberately restrained. He isn't trying to be a "fast rapper." He's being a narrator.

- The Vocals: Chester’s "In the end, it doesn't even matter" is arguably one of the most recognizable vocal lines in rock history. His ability to go from a whisper to a scream without losing the melody is what made him a unicorn.

- The Ending: The way the song fades out with that same piano riff brings the whole thing full circle. It suggests that the cycle of trying and failing is just going to repeat.

Actionable Insights for Fans and Creators

If you’re a musician or a creator looking at the success of Linkin Park In the End, there are actual lessons to be learned here. It wasn't just luck.

- Trust the tension. If there’s a song your band is fighting over, that’s usually the one with the most energy. Chester and Mike’s disagreement over the song is exactly what gave it its edge.

- Simplicity wins. You don't need a thousand chords. You need four notes that people can't get out of their heads.

- Vulnerability is a currency. People connected with this song because it admitted defeat. In a world of "macho" rock, Linkin Park admitted they lost.

- Hybridize your influences. Don't be afraid to put a hip-hop beat under a rock chorus. In 2000, that was "risky." In 2026, it’s the standard, but Linkin Park did it with more sincerity than almost anyone else.

To truly appreciate the song today, listen to the Hybrid Theory 20th Anniversary Edition demos. You can hear the evolution. You can hear the "The End" (the original title) and see how they stripped away the fluff to find the diamond underneath.

The song is a reminder that even if things don't work out—even if you "lose it all"—the act of trying and the art you create during that struggle can end up outlasting the struggle itself. Linkin Park proved that the end isn't always the end; sometimes, it’s just the beginning of a legacy that refuses to die.

Go back and listen to the track today with high-quality headphones. Skip the compressed YouTube version if you can. Listen for the subtle electronic chirps in the background and the way the vocal harmonies stack in the final chorus. You'll realize that even after a thousand listens, there's still something new to find in the wreckage.