You're standing in the workshop. There’s a pile of 10-foot aluminum extrusions on one side and a scribbled list of dimensions on the other. You need twenty pieces at 14 inches, ten at 33 inches, and five at 48 inches. If you just start cutting from the first stick that looks long enough, you’re going to end up with a mountain of 6-inch "offcuts" that are basically expensive trash. It's frustrating. It's expensive. Honestly, it’s just bad math.

This is where a linear cut list optimizer changes the game.

Most people think they can eyeball it. They can't. Even the sharpest carpenter or metal fabricator usually hits a "good enough" threshold that leaves 10% to 15% of their material in the bin. In a world where lumber prices swing wildly and specialized metal alloys cost a fortune, that 15% is your profit margin walking out the door.

The Math Behind the Blade

Let’s get nerdy for a second. This isn't just a simple calculator trick. In the world of computer science, what we’re doing with a linear cut list optimizer is solving a variation of the "One-Dimensional Bin Packing Problem." It’s actually NP-hard. That sounds like academic jargon, but it basically means as you add more parts and different stock lengths, the number of possible combinations explodes.

You can't solve it perfectly by hand in a reasonable amount of time.

A good optimizer uses algorithms—often things like the "First Fit Decreasing" (FFD) or more complex "Branch and Bound" methods—to cycle through thousands of permutations in milliseconds. It looks at your "stock" (the long pieces you have) and your "demands" (the pieces you need) and plays Tetris until the gaps are as small as humanly possible.

Why Kerf Changes Everything

I’ve seen guys download a free app, run the numbers, and then ruin an entire batch of material because they forgot the kerf.

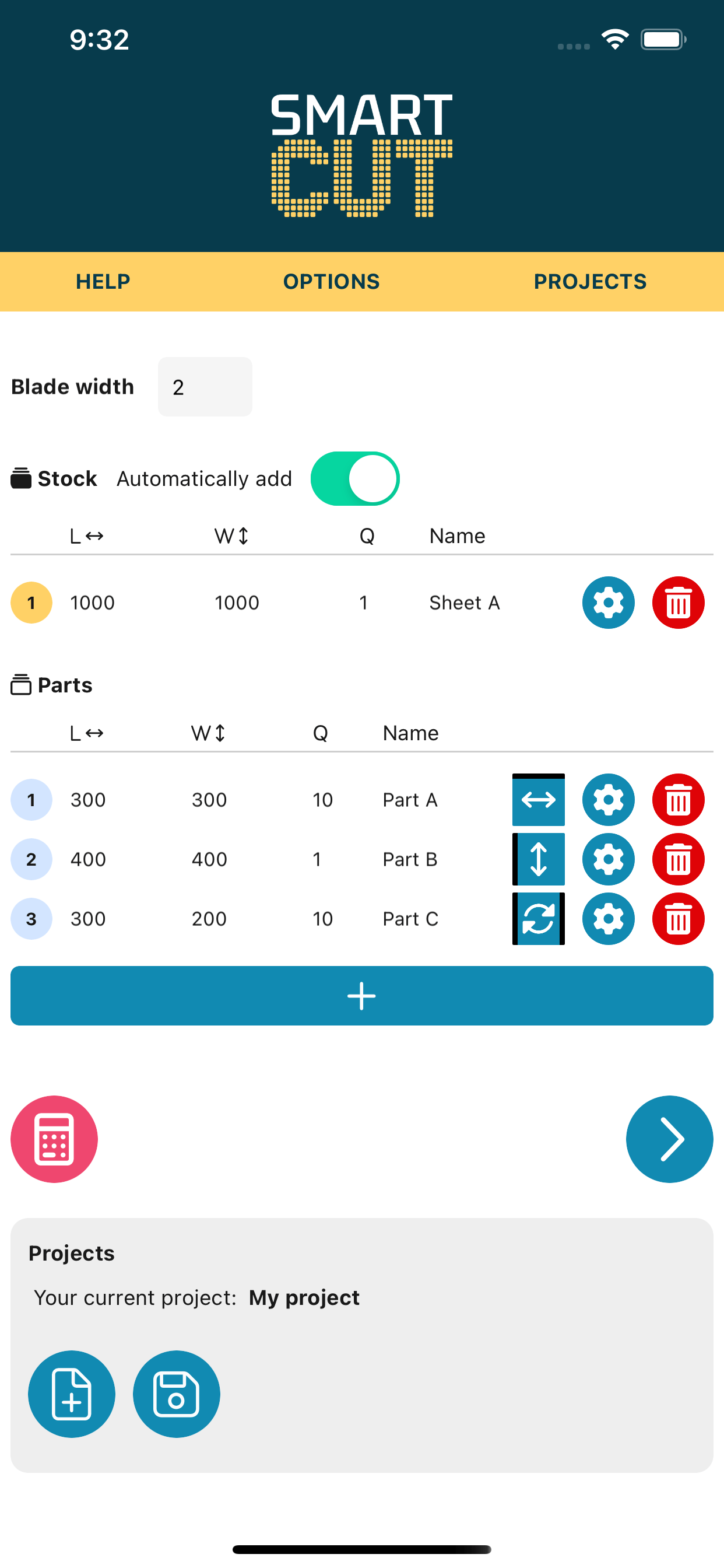

The kerf is the width of the saw blade. If you’re using a beefy miter saw with a 1/8-inch blade, every single cut you make literally turns 1/8-inch of wood into sawdust. If you make ten cuts, you’ve lost over an inch of material. If your linear cut list optimizer doesn't let you input the specific blade thickness, it’s a toy, not a tool. Professional-grade software like CutList Plus or specialized web tools like OptiCutter bake this into the logic. You tell it your blade is 3mm, and it ensures that 3mm is accounted for between every segment.

Real-World Savings: Not Just a Theory

Think about a small cabinet shop. They might go through 500 linear feet of face-frame material a week. If they optimize and save just 5%, that’s 25 feet. Over a year? That’s 1,300 feet of hardwood. At $4 a foot, that’s over $5,000 staying in the bank account.

It’s not just about the money, though. It’s the mental load.

Ever get to the end of a project and realize you're one 12-inch piece short, but all you have left are 11-inch scraps? It’s the worst feeling. You have to stop everything, get in the truck, drive to the supplier, buy one more 8-foot stick, and drive back. You just lost two hours of labor. An optimizer prevents the "emergency hardware store run" because it tells you exactly what to buy before you even start.

The Misconception of "Shortest First"

A lot of beginners think they should cut their shortest pieces first to use up odd ends. That is almost always wrong.

Actually, the "Best Fit" logic usually dictates that you should fit your longest, most awkward pieces into your stock first. Why? Because long pieces are the hardest to place. If you use up your big stock on tiny parts early on, you won't have anything left for that 72-inch header you need later.

A linear cut list optimizer understands this hierarchy. It prioritizes the "hard" cuts. Sometimes the layout it gives you looks weird. It might tell you to cut one long piece, one medium piece, and one tiny piece from a single board, leaving a weirdly specific 2-inch gap. Trust the math.

🔗 Read more: Chinese Sans Serif Font: Why Most Designers Are Still Getting it Wrong

Different Types of Optimization

Not all tools are built the same. You've got basic web-based calculators, and then you've got full-blown ERP integrations.

- Standard Linear: One dimension. Length. Think pipes, tubes, 2x4s, and moldings.

- Sheet/Panel (2D): This is different. This is for plywood or sheet metal where you have to worry about length, width, and grain direction.

- Inventory-Aware: This is the pro level. It doesn't just look at what you need; it looks at what you already have in your scrap rack.

Managing the Scrap Pile

We all have that corner of the shop filled with "it's too good to throw away" offcuts. Most of it eventually becomes a fire hazard.

A high-end linear cut list optimizer allows you to input your "remnants." Before the software tells you to go buy a new 20-foot stick of steel tubing, it checks if those three 7-foot pieces in the corner can handle the job. This is where the real "green" benefit comes in. Reducing waste is great for the planet, sure, but it's even better for your floor space.

The "Grain Direction" Trap

In linear optimization, we usually assume the material is uniform. But if you’re working with high-end architectural trim or certain types of grained plastics, you can’t just flip the piece around. You have to maintain the orientation.

Some "dumb" optimizers will suggest flips or rotations to save a fraction of an inch, which results in a finished product that looks like a patchwork quilt because the light hits the grain differently. Always check if your software supports "directional" constraints.

How to Actually Use This Data

Once the optimizer spits out a PDF or a cut map, don't just hand it to the saw operator and walk away.

Labels matter.

The most efficient cut list in the world is useless if you end up with 50 pieces of slightly different lengths and no idea which one is "Part A" and which is "Part J." Use a system. Many optimizers generate labels or QR codes. If you're low-tech, just use a blue painter's tape and a Sharpie.

- Input your stock: List exactly what you have or what you can buy (e.g., 8ft, 10ft, 12ft lengths).

- Input your parts: Be precise. Don't round up.

- Set the kerf: Check your actual saw blade.

- Run the solve: Look for the "Yield" percentage. Anything above 90% is usually excellent.

- Review the "Remnants": Decide if the leftover pieces are worth keeping or if they’re truly trash.

The Limitations of Software

Let's be real: no software knows your material perfectly. It doesn't know there's a huge knot 3 feet into that 2x4. It doesn't know the end of the aluminum pipe is dented from the forklift.

You still need a human eye.

I always suggest adding a "deficiency factor." If the optimizer says you need exactly 10 boards, buy 11. It’s the "just in case" tax. The optimizer's job is to tell you how to cut those 11 boards for the least amount of waste, but it can't account for a bad knot or a "measured twice, still cut it wrong" moment.

Setting Up Your Workflow

Stop using a pencil and a napkin. Seriously.

Start by downloading a simple CSV template. Most optimizers allow you to import data from Excel or Google Sheets. This is a massive time-saver if you're doing a big project like a deck or a production run of furniture. You can keep your master list in a spreadsheet and just "feed the beast" when it's time to cut.

If you’re doing this for a business, look into "Nest" optimization. While linear is great for bars and beams, nesting is the gold standard for anything that involves irregular shapes. But for 90% of construction and fabrication, a solid linear cut list optimizer is the MVP of the shop.

The goal isn't just to save a few bucks. It's about the flow. When you have a printed cut map, the decision-making is done. You aren't standing over the saw, second-guessing yourself, trying to remember if you already cut the 42-inch pieces. You just follow the map. It turns a stressful afternoon of "hope I have enough" into a rhythmic, productive session.

Check your blade width. Measure your stock. Run the numbers. You'll be surprised how much wood you've been throwing away all these years.

Actionable Next Steps

To get started with linear optimization today, begin by auditing your current waste. Take the scrap bin from your last project and calculate the total linear footage versus what you actually used. If that number is higher than 10%, you’re a prime candidate for an optimizer. Next, find a tool that fits your specific needs—use a simple browser-based solver for one-off home projects, but invest in a dedicated desktop application if you're handling inventory. Finally, always calibrate your "kerf" setting by measuring the actual gap left by your saw blade in a scrap piece of material; assuming it's exactly 1/8-inch is a common mistake that leads to accumulated errors across a long cut list.