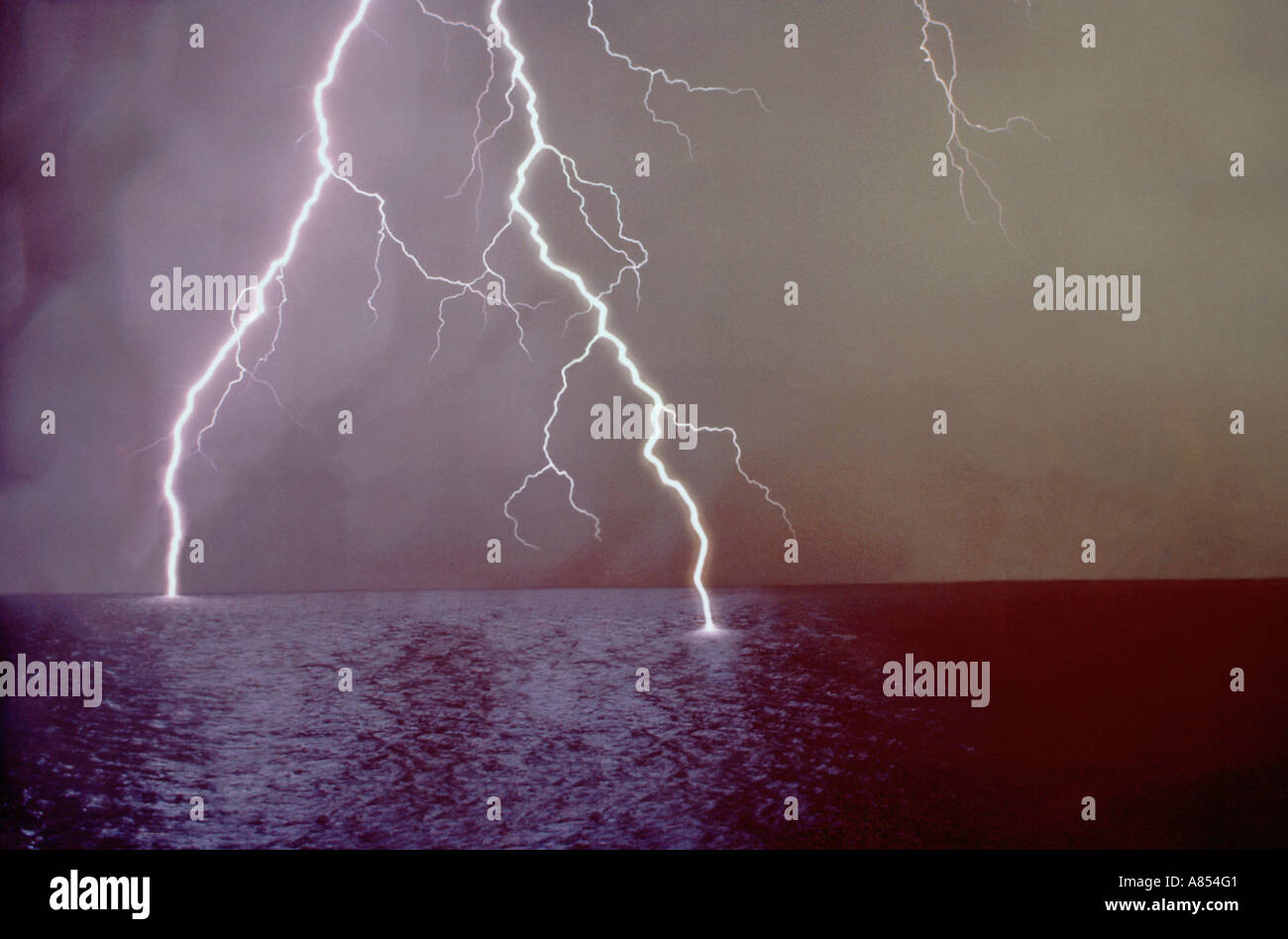

You’ve seen the photos. A jagged, neon-violet vein rips through a charcoal sky, connecting directly with the black expanse of the Atlantic. It looks like a scene from a high-budget disaster flick. But if you’re standing on the beach or, worse, bobbing in a boat, that cinematic beauty feels a lot more like a death sentence. Most of us grew up hearing that water and electricity are a lethal pair. We were told to sprint for the car the second we heard a rumble.

Is it actually that dangerous?

The short answer is yes. Lightning striking the ocean is a massive discharge of energy—anywhere from 100 million to 1 billion volts. To put that in perspective, the outlet you use to charge your phone is pushing 120 volts. When that much juice hits the saltwater, things get weird. Saltwater is an incredible conductor. Because of all those dissolved ions, the electricity doesn't just sink; it spreads across the surface. This is why you’ll rarely see a "fried fish" floating exactly where the bolt hit. The physics are a bit more nuanced than a cartoon toaster in a bathtub.

The Physics of the "Surface Spread"

When lightning hits the sea, it doesn't act like a spear piercing the water. It acts more like a blanket thrown over a bed. Since saltwater is highly conductive, the current chooses the path of least resistance, which happens to be the surface. This is a phenomenon known as the "skin effect." Basically, the electricity stays mostly in the top few feet of the water column.

If you’re a shark cruising at fifty feet deep? You probably won't even notice. But if you're a dolphin leaping for air or a human doing the breaststroke? That’s where the trouble starts.

National Weather Service (NWS) data suggests that while lightning strikes over the ocean are technically less frequent than strikes over land, they are often more powerful. Land heats up faster than water, which usually fuels the convection needed for thunderstorms. However, when those storms drift off the coast or form over warm currents like the Gulf Stream, they become absolute monsters.

💡 You might also like: Flights to Chicago O'Hare: What Most People Get Wrong

Why Boats Are Basically Giant Lightning Rods

If you’re out on a boat, you are officially the tallest thing for miles. In the eyes of a storm cloud looking to dump its electrical load, your mast or your head is a "streamer" waiting to happen.

I’ve talked to sailors who’ve experienced "St. Elmo’s Fire." It’s this eerie, glowing blue plasma that dances on the tips of masts right before a strike. It looks magical. It is actually a terrifying warning that the air is ionized and a strike is imminent.

Modern boats are supposed to be grounded. This means there’s a heavy copper strip or plate on the hull that’s meant to divert the strike safely into the water. But "safe" is a relative term. Even with a lightning protection system, the electromagnetic pulse (EMP) from a direct hit can fry every piece of electronics on board. Your GPS? Dead. Your radio? Toast. Your engine’s computer? Probably melted. You’re left sitting in a dark, silent boat in the middle of a storm.

Real-World Incidents and Statistics

It's not just a theoretical fear. Take the case of the Rebel Soul, a 42-foot catamaran that was struck off the coast of Florida a few years back. The crew described a sound louder than a gunshot and a smell like ozone and burning plastic. The bolt blew out the bottom of the hull in several tiny pinholes. They didn't sink immediately, but they were taking on water while their navigation systems were completely dark.

The Florida coast is actually the lightning capital of the U.S. According to Vaisala’s annual lightning reports, places like the Gulf of Mexico see a staggering density of strikes. Between 2017 and 2022, Florida averaged over 200 strikes per square mile. When you factor in the sheer number of boaters in those waters, the math gets scary.

📖 Related: Something is wrong with my world map: Why the Earth looks so weird on paper

What Happens to the Fish?

Everyone asks this. If lightning hits the water, why aren't there thousands of dead tuna floating around the next morning?

It comes back to the "skin effect" mentioned earlier. Most fish aren't at the very surface when a storm is raging; the choppy waves usually drive them a bit deeper. Since the electricity spreads horizontally across the surface rather than vertically into the depths, the vast majority of marine life is shielded by the very water they live in.

However, there are exceptions. There have been documented cases of "mass kills" in shallow estuaries or near the shore where the water isn't deep enough for the fish to escape the current. In 1932, a strike in a shallow bay in Japan reportedly killed hundreds of fish in a single go. But in the open ocean? It’s a drop in the bucket.

Misconceptions: The "Rubber Sole" Myth

You’ve heard it before: "You’re safe if you’re wearing rubber boots" or "The rubber tires on your car protect you."

Total nonsense.

👉 See also: Pic of Spain Flag: Why You Probably Have the Wrong One and What the Symbols Actually Mean

A lightning bolt has just traveled through miles of air—which is a terrible conductor. A half-inch of rubber on your deck shoes isn't going to stop it. If you’re on a boat, the reason you’re (relatively) safe inside a cabin isn't the flooring; it’s the "Faraday Cage" effect. If the boat has a metal hull or a properly grounded lightning rod system, the electricity travels around the outer shell of the structure and into the water, bypassing the people inside.

Survival and Safety: What To Actually Do

If you find yourself on the water and a storm rolls in, you need to move. Fast.

- Get to Shore: This is obvious, but people wait too long. If you hear thunder, you are within striking distance.

- Drop the Outriggers: If you’re fishing, get those long carbon fiber or metal poles down. They are lightning magnets.

- The "Low" Position: If you’re in a small open boat like a kayak or a center console with no cabin, get as low as possible in the middle of the boat. Do not touch anything metal. Don't be the tallest point.

- Disconnected Electronics: If you have time, unplug your expensive fish finders and radios. It might save them from the surge.

- The 30/30 Rule: It’s an oldie but a goodie. If you see lightning, count. If thunder happens within 30 seconds, get inside. Stay there for 30 minutes after the last roar of thunder.

Practical Steps for Ocean Travelers

Honestly, the best way to handle lightning striking the ocean is to never be there when it happens. Before you head out, check the Lifted Index (LI) on weather apps. A negative LI indicates atmospheric instability—the perfect breeding ground for a strike.

If you are planning a long-range cruise, invest in a dedicated lightning dissipator for your mast. While experts like those at the University of Florida’s International Center for Lightning Research and Testing (ICLRT) debate whether these can actually prevent a strike, they certainly help in directing the energy if a hit occurs.

Check your hull's bonding system. Ensure your copper grounding plate isn't covered in barnacles or thick anti-fouling paint, which can insulate it and force the lightning to find a more destructive path out of the boat—like through your engine block.

Stay off the water when the sky turns that specific shade of bruised purple. No fish is worth 100 million volts.

Next Steps for Safety:

- Download a high-resolution radar app like MyRadar or RadarScope that shows lightning strike density in real-time.

- Inspect your vessel’s grounding system; look for green corrosion on copper wires which can increase resistance.

- Practice a "storm drill" with your crew so everyone knows exactly which metal surfaces to avoid touching when the sky gets dark.