You’ve seen the photos. Those neon, glowing, 3D images of cells that look like something out of a sci-fi movie. Most of those come from multi-million dollar electron microscopes or confocal setups that take up an entire room. But honestly? The humble light microscope is still the backbone of every serious lab on the planet. Whether you’re a med student trying to identify a rogue white blood cell or a hobbyist looking at pond water, the light microscope and parts that make it work are essentially the "OG" of scientific discovery. It’s accessible. It’s fast. And unlike an electron microscope, it lets you look at things while they are actually still alive.

I remember the first time I saw a tardigrade—a water bear—under a basic compound scope. It wasn't just a static image; it was a living, breathing creature kicking its little legs. That’s the magic. But if you don't understand the glass and the gears behind the eyepiece, you’re basically just looking at blurry blobs.

The Core Anatomy: Breaking Down the Light Microscope and Parts

Think of a microscope like a high-precision sandwich. You’ve got the light source at the bottom, the specimen in the middle, and your eyes at the top. Everything in between is there to bend light.

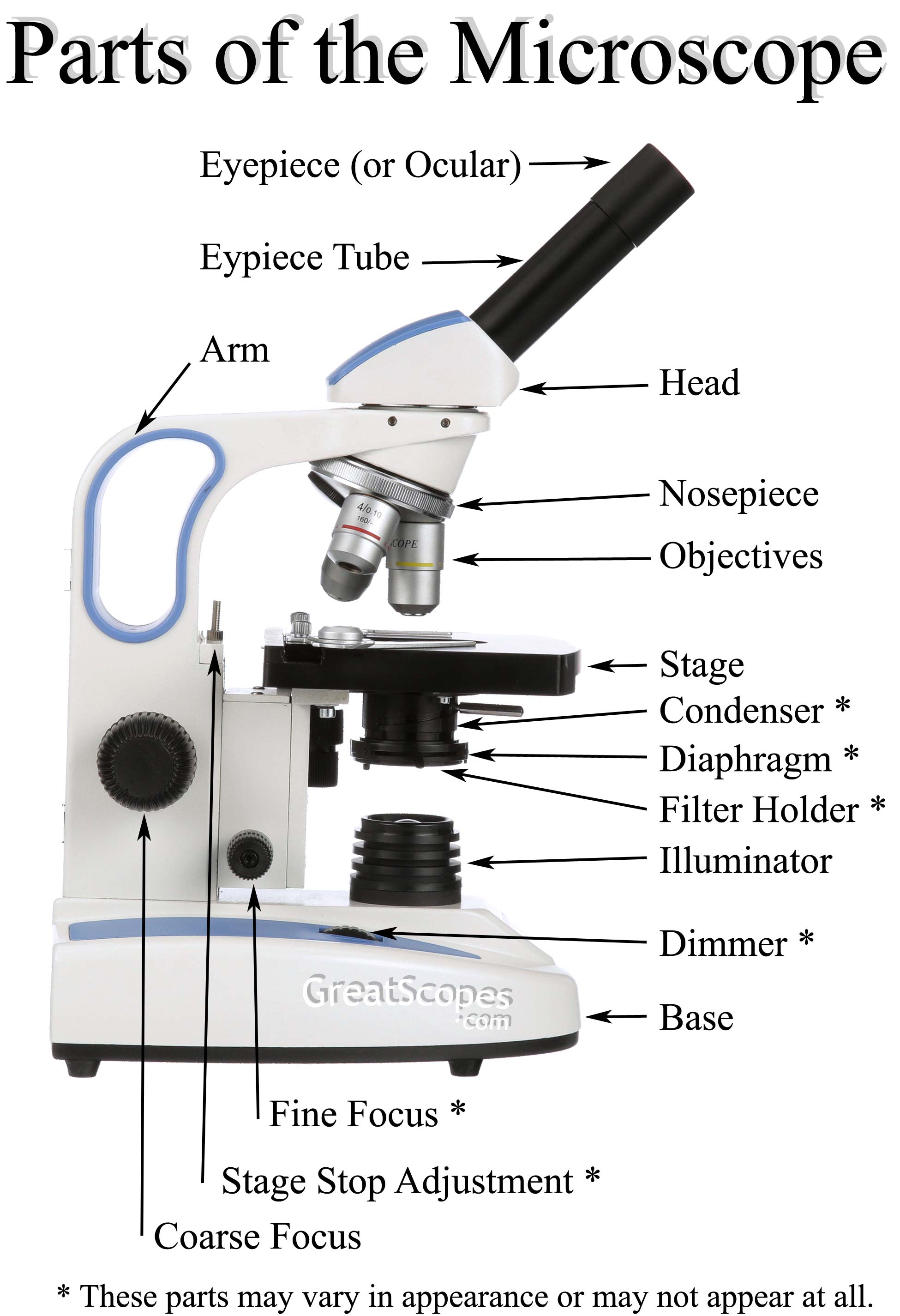

The head is the upper part that holds the optical elements. You’ve got the eyepiece, or the ocular lens, which is what you actually press your face against. Usually, these have a 10x magnification. Then you’ve got the arm, the sturdy backbone you should always grab when carrying the thing. Please, for the love of all that is holy, don't carry it by the stage.

Down at the bottom is the base, which houses the illuminator. In old-school vintage models, this was just a mirror that you had to angle toward a window, which was a nightmare if it was a cloudy day. Modern scopes use halogen or LED bulbs. LED is better because it doesn't cook your specimen. If you’re looking at live bacteria and your light source is too hot, you’re basically microwaving your subject before you can even focus.

The Objective Lenses: Where the Heavy Lifting Happens

This is the business end. The objective lenses are those shiny cylinders hanging off the revolving nosepiece. Usually, you’ll find four of them: 4x (scanning), 10x (low power), 40x (high power), and 100x (oil immersion).

The 100x lens is a tricky beast. It’s designed to be used with a literal drop of cedarwood or synthetic oil placed directly on the slide. Why? Because as light travels from glass to air, it bends and scatters. The oil has the same refractive index as glass, so it keeps the light beams straight, allowing for a crisp image at insane magnifications. If you use the 100x lens without oil, it’ll look like you’re trying to peer through a bowl of milk.

The Stage and the Substage

The stage is the flat platform where the magic happens. Most modern "student" or "professional" scopes use a mechanical stage. This has knobs that allow you to move the slide left, right, up, and back with precision. If you’re using a cheap scope with just stage clips, you have to move the slide with your fingers, which is like trying to perform surgery with oven mitts.

Underneath the stage sits the condenser. People ignore this part, but it’s vital. It gathers the light from the bulb and concentrates it into a tight beam. Inside the condenser is the iris diaphragm. Think of it like the pupil of your eye. You can open it up to let in more light or close it down to increase contrast. If your image looks washed out and "flat," close the diaphragm a bit. It’ll make the edges of the cells pop.

👉 See also: Marie Curie: What Most People Get Wrong About the First Female to Win a Nobel Prize

Focus and Resolution: The Great Misconception

Everyone asks, "What’s the magnification?" That is the wrong question. Magnification is easy; you can blow an image up as much as you want, but if it's blurry, it's useless. What actually matters is resolution.

Resolution is the ability to distinguish two separate points as distinct entities. If your resolution is bad, those two points just look like one big smudge. This is limited by the wavelength of visible light. No matter how good the glass is, a standard light microscope can’t see things smaller than about 200 nanometers. This is why we can see bacteria (which are micrometers in size) but we can’t see individual viruses (which are nanometers in size) without switching to electron microscopy.

How to Actually Focus Without Breaking Glass

You have two knobs: Coarse adjustment and Fine adjustment.

- Start with the lowest power objective (the 4x).

- Crank the stage all the way up using the coarse knob.

- Slowly move it down until the image appears.

- Switch to a higher power.

- Only use the fine adjustment knob once you are at 40x or 100x.

If you use the coarse knob at high power, you run the risk of driving the lens straight through the glass slide. It’s a loud, expensive "crunch" that every biology student eventually hears in a quiet lab. It sucks. Don't be that person.

The Different "Flavors" of Light Microscopy

Not all light microscopes are built the same. The one we’ve been talking about is the Brightfield microscope. It shines light through the sample, so the background is bright and the specimen is dark. It’s great for stained tissues—like a pink and purple slice of liver—but it’s terrible for clear, living cells.

To see clear cells, scientists use Phase Contrast. This is a clever trick where the light microscope and parts are adjusted to shift the phase of the light waves. It turns subtle differences in cell density into differences in brightness. It makes transparent amoebas look like they have shadows and depth.

👉 See also: Buying the Apple Store MacBook Air 15: What I Wish I Knew Before Checking Out

Then there’s Fluorescence. This is the one that produces those glowing images. You hit the sample with a specific wavelength of light (like blue), and the chemicals in the sample (fluorophores) spit back a different color (like green). It’s how we track specific proteins moving inside a cell in real-time. It’s incredible, but the setup requires specialized filters and a much more powerful light source than your average classroom scope.

Common Pitfalls and Maintenance

Microscopes are surprisingly delicate. The lenses are coated with special films that can be scratched by a single grain of dust.

- Never use a paper towel or your shirt to clean a lens. Use lens paper.

- Clean the oil off immediately. If you leave oil on the 100x lens, it can seep into the internal housing and ruin the cement holding the glass in place.

- Check the bulb. If the light isn't turning on, 90% of the time it's a blown fuse or a dead bulb, not a broken scope.

Real-World Impact: Why We Still Use Them

In 2026, you might think we’d have moved past glass lenses and mirrors. But in clinics across the globe, the light microscope is the primary tool for diagnosing malaria, tuberculosis, and various cancers. In metallurgy, they use reflected light microscopes to check for microscopic cracks in airplane parts.

It’s about "speed to answer." You can prep a slide for a light microscope in about 30 seconds. For an electron microscope? You might spend days fixing, dehydrating, and coating the sample in gold. Sometimes, you just need to know if there's bacteria in a sample right now.

Practical Next Steps for Better Microscopy

If you’re looking to improve your results, start with the Koehler Illumination technique. It’s a specific way of aligning the light path that ensures the light is perfectly even across your field of view. Most people just turn the light on and start looking, but taking the sixty seconds to align the condenser and the diaphragm makes a world of difference in image quality.

✨ Don't miss: US Marine Corps Vehicles: Why the Corps is Trading Tanks for High-Tech Speed

Check your objectives for a number called Numerical Aperture (NA). It’s usually printed right next to the magnification (e.g., 40x / 0.65). The higher the NA, the better the resolution. If you’re buying a microscope, prioritize a high NA over a high magnification.

Keep your workspace clean. Dust is the enemy of optics. Cover your microscope with a dust jacket when you’re not using it. It sounds simple, but a clean microscope will last fifty years, while a neglected one will be a paperweight in five. Stop obsessing over the digital zoom on your phone or computer screen and focus on the physical glass—that’s where the real data lives.