Ever looked in the mirror while glancing down at your phone and noticed one eyelid staying higher than the other? It’s subtle. Most people miss it entirely. But if you’ve noticed a sliver of white sclera—that’s the white part of your eye—peeking out between your upper eyelid and your iris when you look downward, you’re looking at lid lag.

It isn't just a quirk of your facial structure.

Honestly, it’s one of those clinical signs that makes doctors sit up a little straighter in their chairs. In the medical world, we often call this Von Graefe’s sign. It isn't a disease itself, but rather a physical manifestation of something else happening deep inside your body’s regulatory systems. Usually, when you look down, your upper eyelid follows the movement of your eye in a smooth, synchronized motion. With lid lag, the lid "lags" behind. It stays retracted. It’s a mechanical failure of the eyelid’s ability to relax as the globe of the eye rotates downward.

What is Lid Lag Really?

To understand why this happens, you have to look at the anatomy of the levator palpebrae superioris. That’s the muscle responsible for lifting your eyelid. You also have the Müller’s muscle, which is controlled by your sympathetic nervous system—the "fight or flight" part of your brain.

When everything is working correctly, these muscles relax as you look down.

But in people with lid lag, these muscles are often overstimulated or structurally thickened. Imagine a window shade that gets stuck halfway up when you try to pull it down. That’s basically what’s happening here. The most common culprit? Thyroid Eye Disease (TED), also known as Graves’ Ophthalmopathy.

But here’s the thing: people often confuse lid lag with ptosis. They aren't the same. Not even close. Ptosis is a "droopy" eyelid where the lid sits too low. Lid lag is the exact opposite—the lid sits too high during downward gaze. It’s a distinction that matters immensely for diagnosis.

The Connection to Graves’ Disease

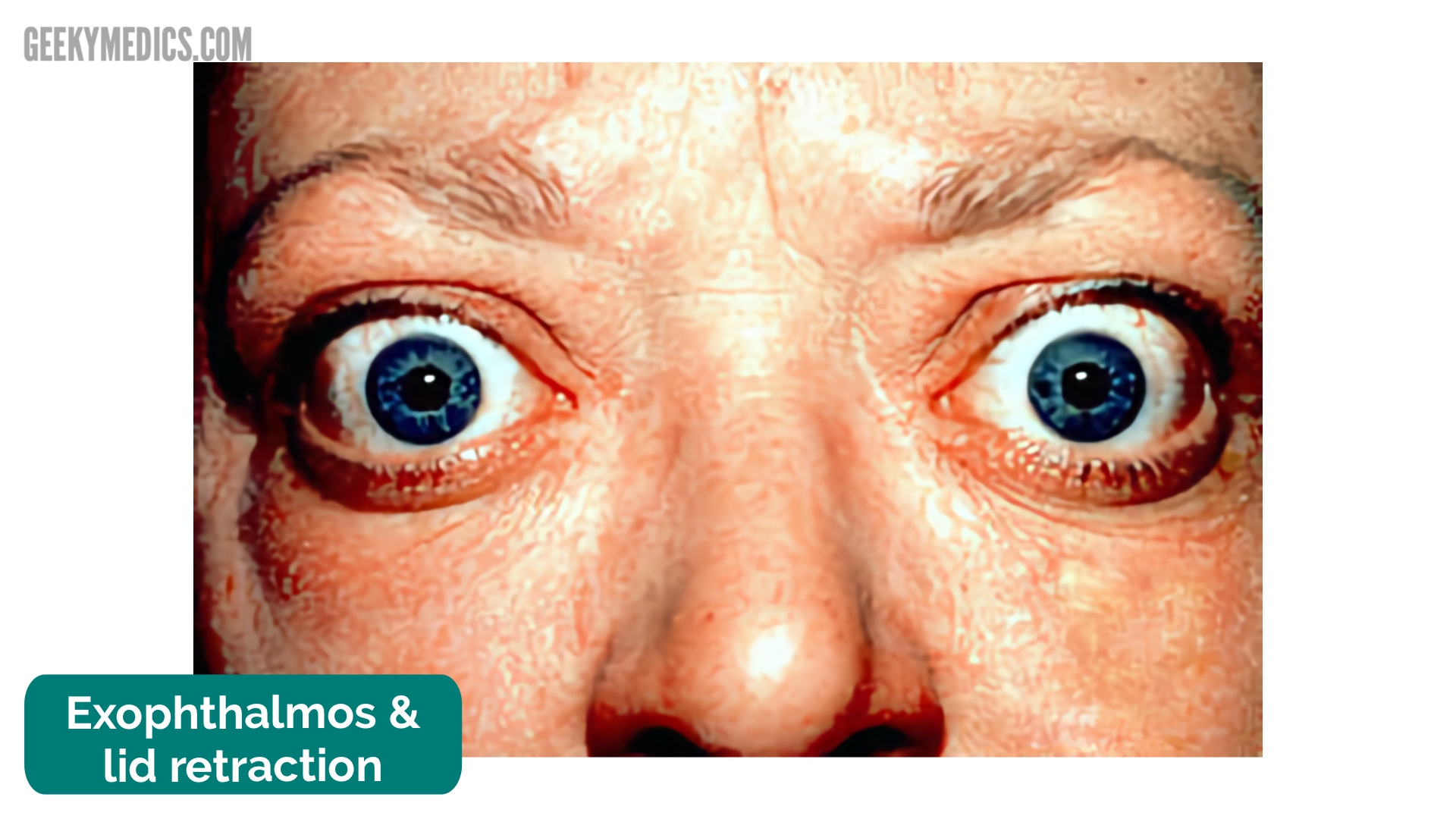

If you walk into an endocrinologist’s office with bulging eyes (proptosis) and a clear case of lid lag, they’re almost certainly going to test your thyroid.

Graves’ disease is an autoimmune disorder where your immune system attacks the thyroid gland, but it also has a weirdly specific affinity for the tissues behind your eyes. The immune system triggers inflammation in the extraocular muscles and the fatty tissue in the eye socket. This inflammation leads to scarring and fibrosis. When the muscles that move the eye become scarred or stiff, they lose their elasticity.

👉 See also: Cleveland clinic abu dhabi photos: Why This Hospital Looks More Like a Museum

Because the muscles are stiff, they can't "let go" properly.

According to research published in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, nearly 25% to 50% of patients with Graves’ disease will develop some form of thyroid eye disease. Lid lag is often one of the earliest signs. Sometimes it appears even before the blood tests show that your thyroid hormone levels are out of whack.

It’s a warning light on the dashboard.

It Isn't Always the Thyroid

While the thyroid is the usual suspect, it isn't the only one. You have to consider the nerves.

Sometimes, lid lag can be a result of high sympathetic tone. If you’re under extreme stress or consuming massive amounts of stimulants, your Müller’s muscle might just be hyper-contracted. There’s also a condition called periodic paralysis or even certain midbrain lesions that can interfere with the way the brain coordinates eye and lid movement.

I’ve seen cases where it was purely mechanical.

If someone has had aggressive blepharoplasty (eyelid surgery) and the surgeon took a bit too much skin, the lid physically cannot descend all the way. It’s tethered. That’s not a neurological "lag," but it looks identical to the naked eye. This is why a physical exam is so vital. A doctor needs to see if the lag is bilateral (both eyes) or unilateral (one eye). Unilateral lid lag is much more likely to be caused by a local issue, like a tumor or a specific nerve injury, whereas bilateral lag usually points toward a systemic metabolic issue like hyperthyroidism.

How Doctors Check for Lid Lag

You can actually test this at home, though you shouldn't self-diagnose.

✨ Don't miss: Baldwin Building Rochester Minnesota: What Most People Get Wrong

Hold a pen or your finger about 12 inches from your face at eye level. Slowly move it downward toward your chin while keeping your head perfectly still. Follow the object with only your eyes. If someone watching you sees the white of your eye appearing above the iris as you look down, that’s a positive sign for lid lag.

In a clinical setting, a physician might use a more formalized version of this called the "slow pursuit" test. They’re looking for the timing. Does the lid move immediately? Does it jerk?

The nuance is everything.

Living with the Symptoms

The problem with lid lag isn't just how it looks. It’s what it does to the surface of the eye.

When your eyelid doesn't close properly or stay in the right position, the cornea—the clear front window of your eye—is exposed to the air more than it should be. This leads to exposure keratopathy. Basically, your eye dries out. Fast.

- You might feel a "gritty" sensation, like there’s sand in your eye.

- Your eyes might water constantly (ironically, because they are so dry).

- Light sensitivity becomes a major issue.

- In severe cases, you can develop corneal ulcers, which are incredibly painful and can threaten your vision.

People with thyroid-related lid lag often describe a feeling of "pressure" behind the eyes. It’s uncomfortable. It’s distracting. And honestly, it can be a blow to your self-esteem because it changes the way you look to others. It can give you a "staring" expression that people often misinterpret as being surprised or angry.

Treatment Options and Management

Fixing lid lag usually means fixing the underlying cause. If it’s hyperthyroidism, you get the thyroid under control with methimazole, radioactive iodine, or surgery. But here is the frustrating part: sometimes the lid lag persists even after the thyroid levels are back to normal.

The tissue changes in the orbit are sometimes permanent.

🔗 Read more: How to Use Kegel Balls: What Most People Get Wrong About Pelvic Floor Training

At that point, we look at symptomatic relief. Lubricating drops are the first line of defense. Use the preservative-free ones. They’re better for the long haul. Some people have to tape their eyes shut at night to prevent the cornea from drying out while they sleep.

If the lag is severe and causing vision problems, surgery is an option.

Surgeons can perform a "lid lengthening" procedure. They basically go in and weaken the levator muscle or the Müller’s muscle to allow the lid to drop to a more natural position. It’s delicate work. You don't want to over-correct and end up with ptosis. It’s a balancing act.

There’s also a newer medication called Tepezza (teprotumumab). It’s an IV infusion specifically for thyroid eye disease. It’s been a game-changer for many, reducing the inflammation and muscle swelling that causes the lag in the first place, though it comes with its own set of side effects like hearing changes or muscle cramps.

The Psychological Impact

We don't talk enough about the mental toll.

Your face is how you interface with the world. When your eyes change—when they look "different" or "bulging"—it affects your social confidence. I’ve talked to patients who stopped going to dinner parties because they were tired of people asking if they were okay or why they were staring.

It’s a heavy burden.

Understanding that lid lag is a medical symptom and not a personal failing is a huge step. Finding a support group for Graves’ disease or TED can make a world of difference. You aren't just "staring" at people; your anatomy is reacting to a complex autoimmune process.

Actionable Next Steps

If you think you’ve spotted lid lag in yourself or a family member, don't panic, but do take it seriously. It is a clinical sign that demands an explanation.

- Document it. Take a video of yourself looking slowly from the ceiling to the floor. This gives your doctor a clear visual record that isn't dependent on how you’re feeling that specific minute in the exam room.

- Get a full thyroid panel. Don't just settle for a TSH (Thyroid Stimulating Hormone) test. Ask for Free T3, Free T4, and especially TSI (Thyroid Stimulating Immunoglobulin) antibodies. The antibodies are what tell the real story of Graves’ disease.

- See an Oculoplastic Surgeon or Neuro-ophthalmologist. General optometrists are great, but for lid lag, you want a specialist who deals specifically with the structure of the eye socket and the neurological pathways of the eyelids.

- Protect the surface. Start using high-quality artificial tears immediately. Keeping the cornea hydrated is the best way to prevent long-term scarring while you wait for a diagnosis.

- Check your medications. Some drugs that affect the sympathetic nervous system can mimic these symptoms. Bring a full list of your supplements and prescriptions to your appointment.

Lid lag is a small physical detail with massive diagnostic weight. It’s the body’s way of signaling that something is shifting in its internal chemistry. Pay attention to it. Your eyes are often the first place the body's deeper stories start to become visible.