You’ve probably seen the maps. They look like a chaotic web of neon geometric lines crisscrossing the globe, connecting the Great Pyramid of Giza to Stonehenge or some random hilltop in rural England. It’s a rabbit hole. Honestly, once you start looking at a ley lines earth map, the world starts to look less like a collection of random tectonic plates and more like a carefully designed circuit board.

But here’s the thing. Most of what you see on social media about "energy grids" or "earth chakras" is a relatively modern invention. The real story is weirder. It’s more human.

The concept didn't start with ancient mystics. It started with a guy named Alfred Watkins in 1921. He was an amateur archaeologist and photographer sitting on a hillside in Herefordshire, England. Suddenly, he had a "flash" of insight. He noticed that ancient sites—megaliths, old churches, holy wells, and Iron Age hillforts—seemed to fall into perfectly straight lines across the landscape. He called them "leys," an old English word for a cleared glade or meadow. Watkins wasn't talking about "vibrational frequencies" back then. He thought they were just old trade routes. Simple. Functional.

The Evolution of the Ley Lines Earth Map

Watkins published his findings in a book called The Old Straight Track. He argued that these alignments were markers for prehistoric travelers who needed to navigate dense forests. If you can see a notch in a mountain or a specific standing stone from miles away, you stay on the path. You don't get lost.

Things changed in the 1960s. That's when the New Age movement took Watkins’ map and plugged it into a different socket.

John Michell, a key figure in the counterculture movement, wrote The View Over Atlantis in 1969. He’s basically the reason people today associate a ley lines earth map with "telluric energy" or "fey power." He linked these British alignments to the Chinese concept of lung mei (dragon paths) and the Nazca lines in Peru. Suddenly, these weren't just paths for prehistoric merchants; they were arteries for the Earth's life force. People started bringing dowsing rods to Stonehenge. They started looking for "vortexes" in Sedona, Arizona. It became a global phenomenon.

💡 You might also like: Human DNA Found in Hot Dogs: What Really Happened and Why You Shouldn’t Panic

Is there actual science behind the grid?

Scientists are skeptical. Usually very skeptical.

Archaeologists point out that if you have enough points on a map (like thousands of ancient churches and burial mounds), you are mathematically guaranteed to find straight lines connecting some of them. It’s called the clustering effect. If you throw a handful of rice on a table, you’ll find three grains that form a perfect line. Does that mean the rice is trying to tell you something? Probably not.

However, there are some interesting anomalies. Geologists have noted that some of these ancient sites are built directly over fault lines. Some people, like the late Paul Devereux, who ran the Dragon Project, spent decades measuring "anomalous energy" at these sites. They looked for ultrasonic pulses and magnetic fluctuations. They found... some stuff. Not enough to rewrite physics textbooks, but enough to make you wonder why ancient people were so obsessed with specific granite outcrops that happen to be slightly more radioactive than the surrounding soil.

Why We Keep Mapping the Earth This Way

We crave order. Our brains are hardwired to find patterns in the noise. When you look at a ley lines earth map, you aren't just looking at geography; you're looking at a human desire to feel connected to the planet. We want to believe the ground beneath us has a pulse.

Think about the "Great North Line" in the UK or the alignment of the pyramids in the Teotihuacán complex in Mexico. These aren't just random placements. They involve sophisticated celestial math. Ancient people were watching the stars, and they reflected that cosmic order onto the dirt. Whether you call that "energy" or just "really good urban planning" depends on your perspective.

📖 Related: The Gospel of Matthew: What Most People Get Wrong About the First Book of the New Testament

Major Nodes on the Global Grid

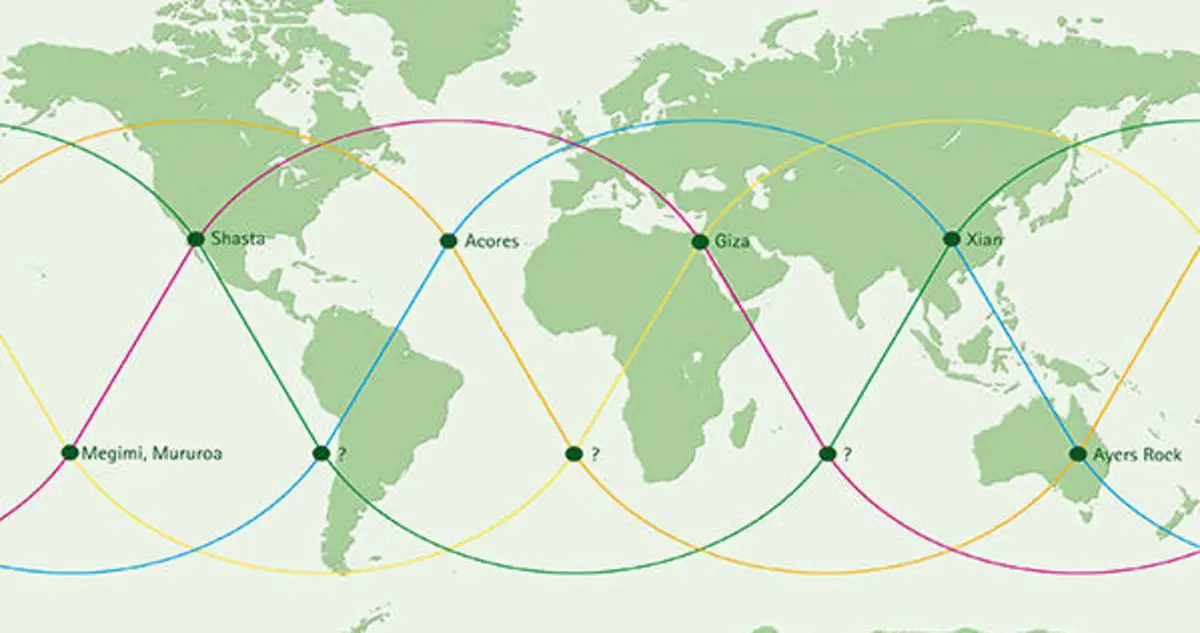

If you look at the most famous versions of the global ley line map—like the one popularized by Ivan P. Sanderson or the "Russian Grid" (Gorbunova, Morozov, and Makarov)—certain spots always pop up:

- Giza, Egypt: The anchor point for almost every global grid theory.

- The Bermuda Triangle: Often cited as a "vile vortex" where lines cross and things go sideways.

- Easter Island: A tiny speck of land in the middle of the Pacific that somehow sits on a major intersection of these hypothesized lines.

- Mount Kailash in Tibet: Considered the spiritual center of the world by several religions and a major "node" in ley line lore.

Is it a coincidence that these places feel "heavy" with history? Maybe. But for the people who spend their lives dowsing these paths, the feeling of "place" is more real than a GPS coordinate.

The Practical Side of the Mystery

So, what do you do with this? If you’re a traveler, looking at a ley lines earth map can actually be a pretty cool way to plan a trip. It takes you off the beaten path. Instead of just hitting the main tourist traps, you start looking for the "in-between" places—the lone standing stones in a farmer’s field or the "holy wells" tucked away in a suburban neighborhood.

You don't have to believe in mystical energy beams to appreciate the aesthetic of an ancient alignment. There is something deeply grounding about standing in a spot where humans have gathered for 5,000 years.

There's also the "Sense of Place" theory in environmental psychology. It suggests that certain landscapes have a tangible effect on the human nervous system. High-contrast horizons, specific mineral compositions in the rock, and even the way sound echoes in a valley can trigger a "sacred" feeling. Maybe "ley lines" are just our way of mapping where we feel most alive.

👉 See also: God Willing and the Creek Don't Rise: The True Story Behind the Phrase Most People Get Wrong

Navigating the Map Yourself

If you want to explore this, stop looking for a "one size fits all" map online. Most of them are just people drawing lines on Google Earth without much context. Instead, look into local folklore. Find the old names of roads. In England, any road with "Stane" or "Street" in the name is likely a Roman road, often built on even older tracks. In the US, look for "Medicine Wheels" or ancient mound builder sites in the Ohio River Valley.

- Get a topographic map. Digital is fine, but paper is better for seeing the "big picture."

- Mark the highest peaks and the oldest known structures. 3. Look for the "notches." Ancient navigators used gaps in hills as "sights" on a rifle.

- Visit the site. Don't just look at the screen. Stand there. See if the horizon feels "right."

The ley lines earth map is ultimately a tool for re-enchanting the world. It’s a way to see the Earth as more than just a resource to be mined or a space to be paved. Whether the lines are "real" in a geological sense matters less than the fact that they've inspired humans to look up from their feet and see the connection between the ground and the stars.

Honestly, the world is more interesting when you're looking for the hidden threads. Even if those threads are mostly in our heads, they still lead us to some of the most incredible places on the planet.

Actionable Insights for the Modern Explorer

If you’re serious about tracing these alignments, start small. Use the OpenStreetMap layers or specialized GIS tools to overlay ancient monument databases onto modern terrain. Avoid the "global grid" maps for a while; they’re too zoomed out to mean anything for a weekend hike. Instead, focus on your local county. You’d be surprised how many "straight trackways" still exist in the form of modern footpaths or boundary hedges.

- Research the "St. Michael's Line": This is the most famous alignment in England, stretching from St. Michael’s Mount to Hopton-on-Sea. It's a great case study in how churches dedicated to St. Michael (the dragonslayer) often sit on high, "energetic" points.

- Check the Geology: Use the USGS or British Geological Survey maps to see if your local "ley line" follows a specific rock strata or fault.

- Document your findings: Take photos of the horizon from these points. Note the alignment of the sun during solstices.

The map isn't the territory. It's just an invitation to go outside and see the patterns for yourself.

Next Steps:

- Search for "Ancient Sites Database" for your specific region to find the "points" for your map.

- Download a Star Chart app (like SkyGuide) to see if local alignments correlate with celestial events.

- Read "The Old Straight Track" by Alfred Watkins to understand the original, non-mystical foundation of the theory.