Chemistry is messy. If you've ever stared at a periodic table and felt like you were looking at a secret code, you aren't alone. One of the biggest hurdles for students and enthusiasts alike is the lewis dot structure for every element, a visual shorthand that tells us how atoms behave. Most people think it’s just about drawing dots around letters. It isn't. It’s actually a map of potential energy and elective magnetism.

Gilbert N. Lewis, the guy who came up with this in 1916, wasn't trying to make your life hard. He wanted a way to visualize the "magic" of the valence shell. Basically, atoms are desperate to be stable. Most of them want eight electrons—the "octet rule"—and these dots represent the players in that high-stakes game.

The Secret Language of Valence Electrons

Forget the inner electrons for a second. They don't matter for bonding. When we look at the lewis dot structure for every element, we only care about the outermost shell. Why? Because that’s where the action happens. It’s like a first date; you’re showing your exterior, not your internal organs.

Take Hydrogen. It’s simple. One dot. It has one electron and it’s looking for a partner. But then you move to something like Oxygen. It has six dots. You’ll notice something specific: we pair them up. Electrons are like roommates who prefer their own rooms until the house gets crowded. We place one dot on each of the four sides (top, bottom, left, right) before we start doubling them up. This isn't just a stylistic choice. It represents the actual orbitals where these electrons live.

👉 See also: Why the GFS Weather Model Forecast Still Rules Your Weekend (And Why It Fails)

Why Transition Metals Break the Rules

Here is where it gets weird. If you try to apply a standard lewis dot structure for every element in the middle of the periodic table—the transition metals—you’re going to have a bad time. Elements like Iron or Gold have "d-orbitals." They are the rebels of the chemistry world.

Honestly, most chemists don't even use traditional Lewis dots for transition metals. It just doesn't work well because those inner-shell electrons start jumping out to participate in bonds. You end up with structures that look more like a chaotic beehive than a neat diagram. If a textbook tells you there is a simple "dot" way to do Chromium, they’re probably oversimplifying it to the point of being wrong.

Breaking Down the Groups

Let's get practical. You can actually predict the dot structure just by looking at the column number on the periodic table.

Group 1 (Alkali metals like Lithium and Sodium) always has one dot. Always. Group 2 (Beryllium, Magnesium) has two. It’s incredibly predictable until you hit the "p-block." For groups 13 through 18, you just subtract ten from the group number. Group 17 (the Halogens like Fluorine and Chlorine) has seven dots. They are one electron away from "perfection," which makes them incredibly reactive and, frankly, dangerous.

The Noble Gas Ego

Helium is the exception that proves the rule. It’s in Group 18, but it only has two dots. Why? Because its first shell is full. It’s happy. It’s stable. It doesn't want to talk to you or any other element. This is why Noble Gases were called "inert" for so long. They have a full house. When you draw the lewis dot structure for every element, the Noble Gases are the finish line. Every other element is just trying to look like them.

Formal Charge: The Hidden Math

Sometimes, you can draw a structure that looks "right" but is actually a physical impossibility. This is where formal charge comes in. It’s a bit of accounting. You subtract the number of dots and lines (bonds) from the element’s natural valence count. If the numbers are wild, the molecule won't exist in nature.

👉 See also: Apple Store at University Town Center: What You Should Know Before Heading to La Jolla

I've seen students draw Carbon with five bonds. Don't do that. Carbon has four valence electrons; it wants four bonds. Five is a "Texas Carbon," and it’s a cardinal sin in organic chemistry.

Beyond the Basics: Expanded Octets

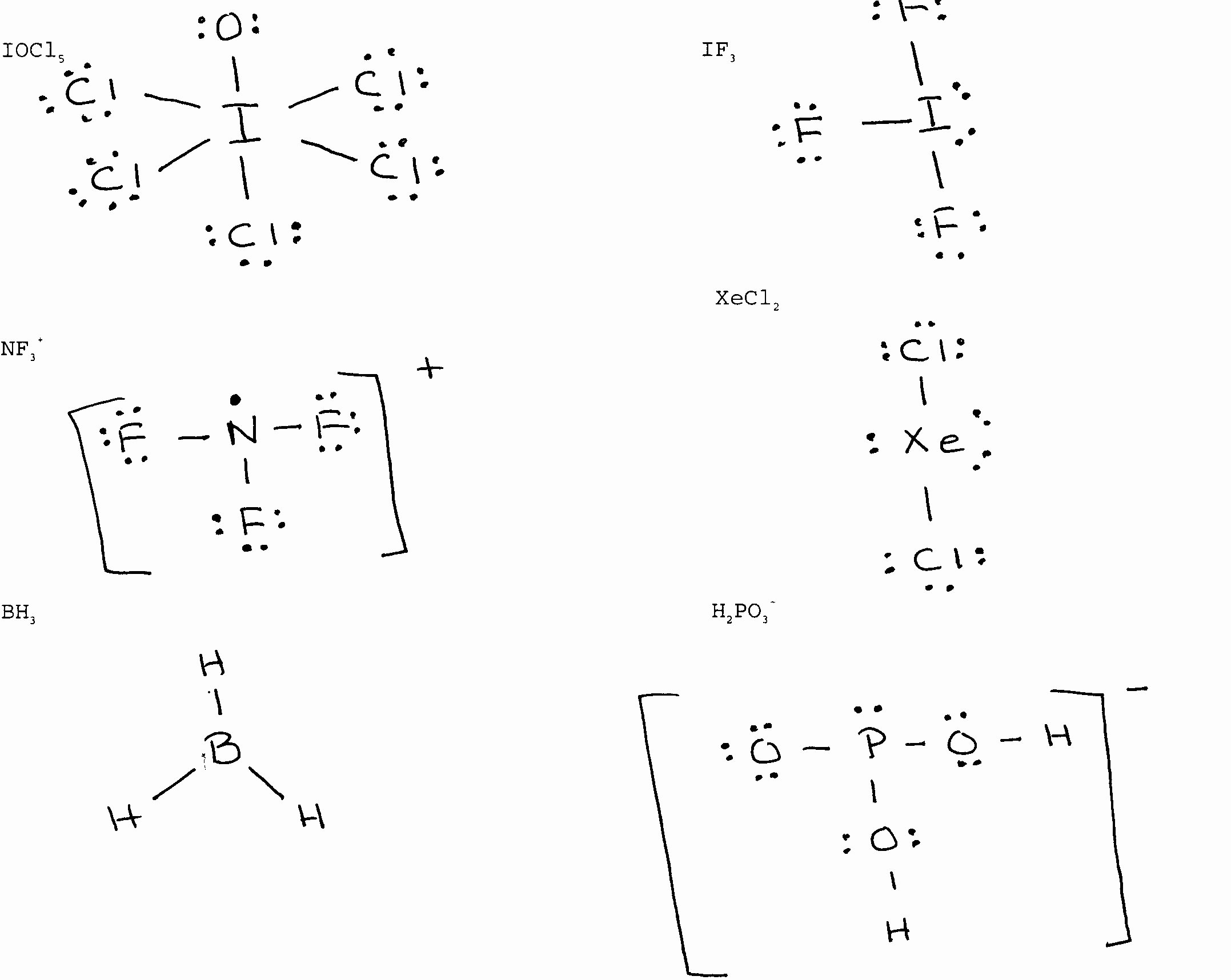

Wait, it gets crazier. Once you get past the second row of the periodic table—specifically elements like Phosphorus or Sulfur—the "octet rule" becomes more of a suggestion. These elements have access to d-orbitals. They can hold ten, twelve, or even more electrons.

Sulfur Hexafluoride ($SF_6$) is the classic example. Sulfur sits in the middle with twelve electrons around it. If you’re trying to find a lewis dot structure for every element and you hit Sulfur, remember that it’s an overachiever. It can expand its shell to accommodate more guests. This is why Sulfur smells like rotten eggs in so many different compounds; its versatility allows it to hook up with almost anything.

💡 You might also like: Finding an iPhone 5c for sale: Why this plastic relic is actually a vibe in 2026

Real World Application: Nitrogen and Life

Look at Nitrogen. Five dots. Two are paired, three are "lone." This configuration is why Nitrogen gas ($N_2$) in our atmosphere is so hard to break apart. It shares those three lone dots to form a triple bond. It’s one of the strongest bonds in nature. Without the specific Lewis structure of Nitrogen, our DNA wouldn't have the stability it needs to exist. Chemistry isn't just dots; it’s the reason you have a genetic code.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

- Crowding the dots: Keep them on the four cardinal sides.

- Forgetting the charge: If you’re drawing an ion (like $OH^-$), you have to add or subtract an electron and put the whole thing in brackets.

- Assuming symmetry: Not every molecule is a perfect cross. Lone pairs take up more space than bonds, which pushes the other atoms away. This is called VSEPR theory, and it’s the reason water is bent, not straight.

Actionable Steps for Mastering Structures

If you want to actually get good at this, stop memorizing and start looking for patterns.

First, identify the total number of valence electrons for the entire molecule. If you're doing a single element, just look at its column. Second, place the least electronegative atom in the center (usually not Hydrogen). Third, connect everything with single bonds. Finally, fill in the remaining dots to satisfy the octets, starting from the outside and moving in.

If you have leftovers, they go on the central atom. If you run out before everyone is happy, you need to start making double or triple bonds. It’s like a puzzle where the pieces can change shape.

The lewis dot structure for every element is ultimately a tool for prediction. By mastering the dots, you can predict whether a chemical reaction will explode, fizzle, or create something entirely new. Start with the first twenty elements. Get comfortable with the patterns of the "Big Four"—Carbon, Nitrogen, Oxygen, and Hydrogen. Once those click, the rest of the periodic table starts to make a lot more sense.