Chemistry can feel like a fever dream of invisible particles and math that doesn't always want to cooperate. Honestly, when you first stare at the periodic table, it's just a grid of letters and numbers. But there is a specific trick—a visual shorthand—that makes sense of the chaos. It's called the lewis dot structure for all elements, and even though it was dreamt up by Gilbert N. Lewis back in 1916, we haven't found a better way to quickly visualize how atoms "shake hands" to form molecules.

Think of it as a social map for atoms. It isn't just about dots; it's about the valence electrons. These are the electrons hanging out in the outermost shell, the ones that actually do the work of bonding. If an atom were a person, the inner electrons would be their internal organs, and the valence electrons would be their hands. You don't care about the organs when you're trying to figure out how to hold hands with someone.

The Logic Behind the Dots

Most people think you just throw dots around an element's symbol and call it a day. It's more systematic than that. You've basically got four "slots" around the symbol—top, bottom, left, and right. You fill them one by one before you start doubling up. This isn't just a rule for the sake of rules; it represents the s and p orbitals where these electrons live.

Take Carbon. It's in Group 14. That means it has four valence electrons. You put one dot on each of the four sides. Boom. You've got four single electrons ready to mingle. This is why Carbon is the "LEGO brick" of life; it can bond in four different directions, creating everything from the graphite in your pencil to the DNA in your cells.

Group by Group: The Pattern

If you're looking at the lewis dot structure for all elements across the main group, the pattern is actually pretty satisfying.

Group 1 (Alkali Metals): These guys, like Lithium or Sodium, have just one dot. They are desperate to get rid of it. They’re the friends who are always trying to give away their furniture because they’re moving—highly reactive and always looking for a way to simplify.

Group 2 (Alkaline Earth Metals): Magnesium and Calcium have two dots. Usually, these are placed on opposite sides or separate sides to show they are ready to form two bonds or, more likely, lose two electrons to become stable ions.

Moving across to the Halogens (Group 17): Look at Fluorine or Chlorine. They have seven dots. They are one dot away from a "full house." This makes them the most aggressive "takers" in the chemical world. They will rip an electron off a passing Sodium atom without thinking twice. That's why salt ($NaCl$) forms so easily; it's a perfect trade.

The Octet Rule and Its Annoying Exceptions

We talk a lot about the Octet Rule. It’s the idea that atoms want eight electrons to feel "complete," like the noble gases in Group 18. Neon and Argon already have eight dots. They are chemically "rich" and don't want to talk to anybody. They're inert.

But science is rarely that clean.

👉 See also: Galaxy S25 SD Card: Why You Probably Won’t Get One (And What to Do Instead)

You’ll run into elements like Boron. Boron is weird. It’s often happy with just six electrons. Then you have the "expanded octet" crowd. Elements in the third row of the periodic table or lower—like Phosphorus or Sulfur—can actually hold more than eight dots. Sulfur can sometimes look like a sunburst with six bonds (12 electrons) in molecules like Sulfur Hexafluoride ($SF_6$). If you try to stick to the "eight is great" rule with Sulfur, you're going to have a bad time.

Transition Metals: Where the System Breaks

Here is what most textbooks gloss over: the lewis dot structure for all elements doesn't work great for transition metals (the block in the middle of the table).

Why? Because transition metals are complicated. They have d-orbital electrons that can act like valence electrons depending on the day of the week and who they're talking to. Iron can be $Fe^{2+}$ or $Fe^{3+}$. Drawing a simple dot structure for Iron doesn't tell you much about how it's going to behave in a complex. For these, chemists usually rely on other models, like Crystal Field Theory or just looking at oxidation states. If you're trying to draw a Lewis structure for Gold, stop. It's not really meant for that.

Why Does This Actually Matter?

You might wonder why we're still using 100-year-old dot drawings in the age of supercomputers and quantum modeling. It’s because the Lewis model predicts geometry.

If you know where the dots (and especially the "lone pairs" of dots that don't bond) are, you can use VSEPR theory (Valence Shell Electron Pair Repulsion). Those lone pairs take up space. They push the other bonds away. In a water molecule ($H_2O$), Oxygen has two lone pairs. These pairs act like invisible "bully" clouds, pushing the Hydrogen atoms down, which is why water is bent and not a straight line. That "bent" shape is the reason water has surface tension and the reason life exists. All because of two pairs of dots you can draw on a napkin.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

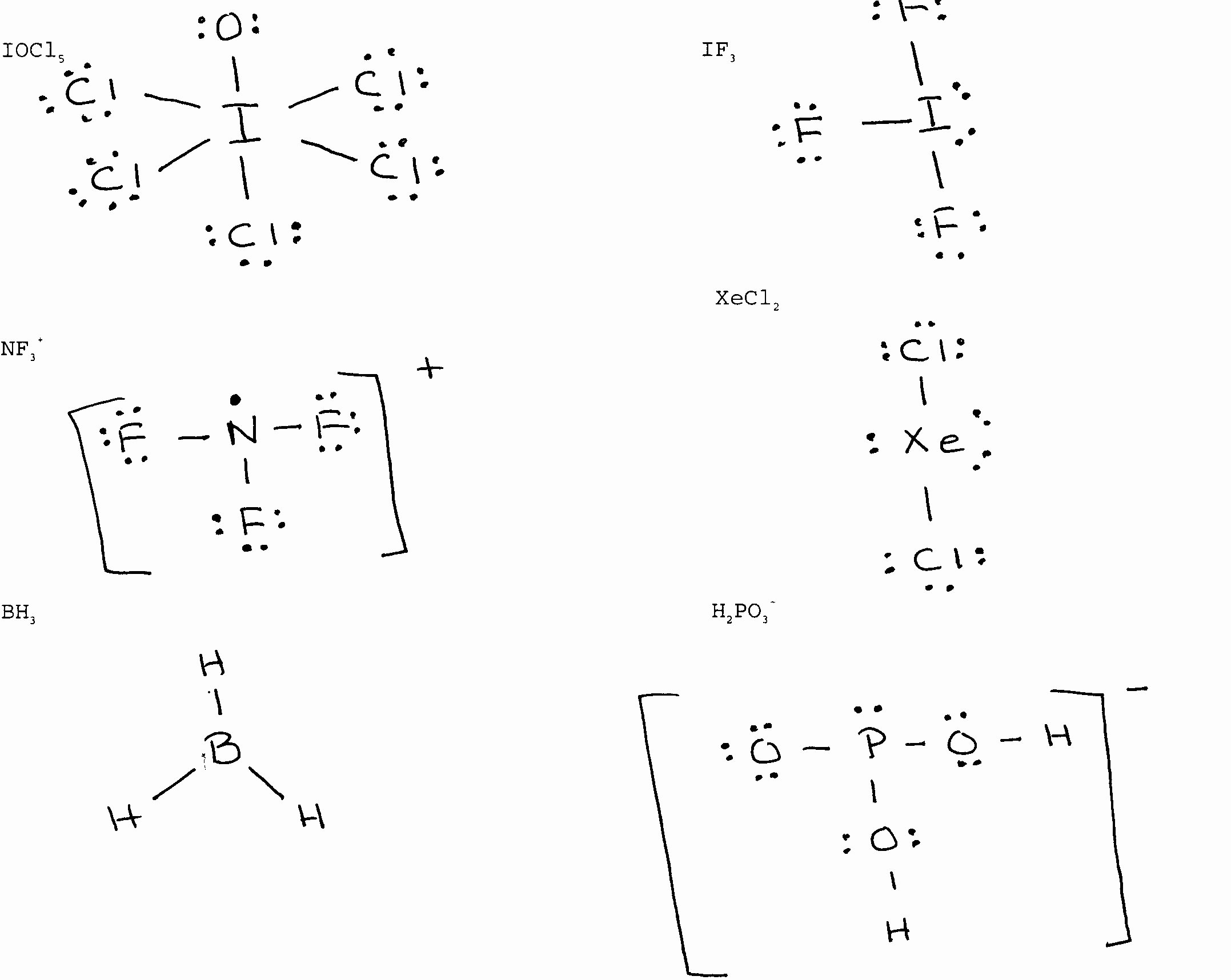

- Forgetting the Charge: If you're drawing an ion, like Sulfate ($SO_4^{2-}$), you have to add extra dots for the negative charge and put the whole thing in brackets.

- Crowding the Dots: Don't just clump them. The four-sided "box" method is your friend.

- Ignoring Hydrogen: Hydrogen only wants two dots (a "duet"), not eight. It’s the tiny exception to the octet rule that everyone forgets on their first quiz.

Practical Steps for Master Mapping

To master the lewis dot structure for all elements, stop trying to memorize the whole table. Focus on the group number.

- Find the Group Number: For main-group elements (Groups 1-2, 13-18), the last digit of the group number tells you exactly how many dots to draw. Group 15? 5 dots. Group 16? 6 dots.

- The "Single First" Rule: Place one dot on each of the four sides of the element symbol before you double them up. This helps you see how many "unpaired" electrons are available for bonding.

- Count Your Total: When moving to molecules, add up all valence electrons from all atoms first. If you don't start with the right "budget" of dots, the structure will never be right.

- Check for Formal Charge: If a structure looks legal but feels "off," calculate the formal charge. Atoms generally prefer to have a charge as close to zero as possible. This is the "pro" way to decide between two different-looking structures that both satisfy the octet rule.

Understanding these structures is basically learning the grammar of the universe. Once you see the dots, you start seeing why molecules hold together—and why they fall apart.