You’ve seen it a thousand times. Someone sits down at the cable machine, grabs the widest part of the bar, and starts yanking it down toward their belly button while leaning back so far they’re basically doing a horizontal row. It’s painful to watch. Not because it’s "wrong" in a moral sense, but because they’re missing out on about 40% of the muscle growth they could be getting. Learning how to do lat pulls correctly isn’t just about moving a weight from point A to point B. It’s about mechanics.

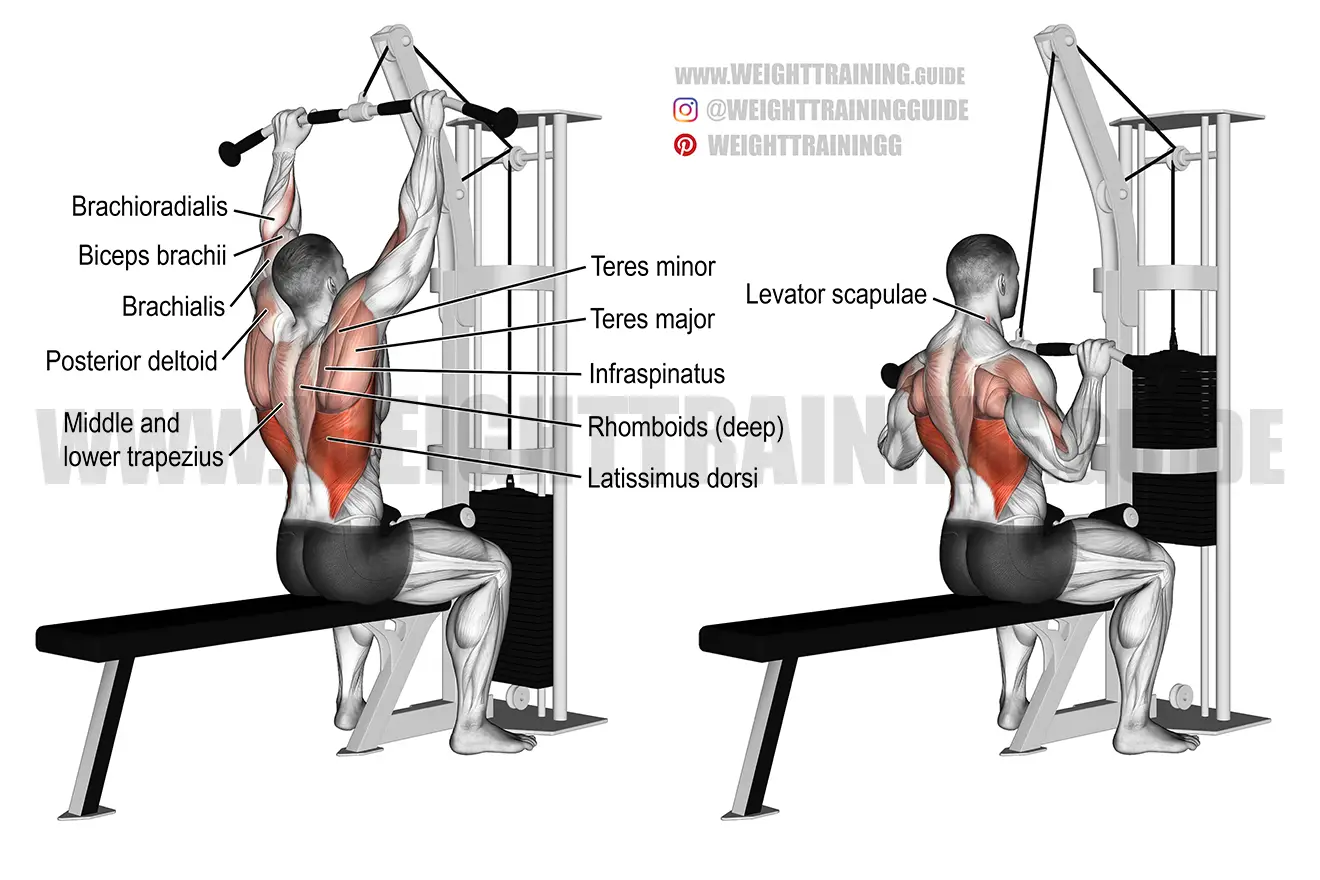

The latissimus dorsi is a massive, fan-shaped muscle. It’s the king of the back. When you nail the form, you get that classic V-taper. When you mess it up? You just end up with tired biceps and a sore lower back.

Why Your Grip Width is Probably Killing Your Gains

Most lifters think a wider grip equals a wider back. It sounds logical, right? Use a wide bar to get wide lats. Except, biomechanically, that’s not really how it works. A study published in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research actually compared grip widths and found that a medium grip—roughly 1.5 times your shoulder width—tended to produce higher muscle activation than an ultra-wide grip.

✨ Don't miss: Why the Break a Leg Game is Actually Terrifying and What Parents Need to Know

When you go too wide, you shorten the range of motion. You’re basically doing a "partial" rep without realizing it. Plus, it puts your shoulders in a precarious, internally rotated position that can lead to impingement over time.

I usually tell people to find the "bend" in the lat bar. Put your pinkies right where the bar starts to angle downward. For most people, this is the sweet spot. It allows your elbows to tuck slightly forward into the scapular plane, which is exactly where the lats want to pull from. If you’re pulling with your elbows flared straight out to the sides like chicken wings, you’re shifting the load onto your rear delts and teres major. Those are fine muscles, sure, but they aren't the lats.

The Secret is in the Pelvis and Ribcage

Here is the thing. Most people focus entirely on their arms. They forget that the lats actually attach to the thoracolumbar fascia—basically your lower back and pelvis.

To actually engage the muscle, you need a stable base. Sit down. Jam your thighs under the pads. If there’s a gap between your legs and the pads, you’re going to end up using your body weight to "cheat" the weight down. You want your feet flat on the floor, pushing down.

Now, the ribcage. Don't flare it. If you arch your back excessively, you’re losing the tension in your core. Keep your abs slightly braced. You want a very slight lean back—maybe 10 to 15 degrees—just enough so the bar clears your face. Any more than that and you’re turning a vertical pull into a row. Rows are great for thickness, but we’re here for the lat pull.

How to do Lat Pulls Without Using Only Your Biceps

"I only feel this in my arms."

I hear that every single week. It’s the number one complaint. The fix is actually mental, but it manifests physically. Think of your hands as hooks. Just hooks. You aren't "pulling" the bar with your hands; you’re driving your elbows into your back pockets.

Try this: wrap your thumb over the top of the bar. A "suicide" or thumbless grip often helps disconnect the mind from the forearm and bicep. When you initiate the move, start by depressing your shoulder blades. Drop them down away from your ears. Then, and only then, start the pull.

Stop the bar at your chin or upper chest. Pulling the bar down to your stomach is useless. Once the bar passes your chin, your elbows start to travel backward rather than downward. When the elbow moves backward, the lat stops being the primary mover and the mid-back takes over. You’re looking for peak contraction, not maximum bar travel.

The Myth of the Behind-the-Neck Pull

We need to talk about the 1980s. For some reason, pulling the bar behind the neck became the "gold standard" for a while. It’s not. It’s actually kind of terrible for most people's rotator cuffs.

Unless you have the shoulder mobility of an Olympic gymnast, pulling behind the neck forces your humerus into an extreme position. It offers no extra lat activation compared to pulling to the front. In fact, most EMG studies show it’s actually less effective. Stick to the front. Your labrum will thank you in ten years.

Variation Matters More Than You Think

You don't always have to use the long, curved bar. In fact, you shouldn't.

- Close-Grip Neutral (V-Bar): This is fantastic for getting a deep stretch. Because your palms face each other, you can pull your elbows further down and forward, which hits the lower fibers of the lats.

- Single-Arm Lat Pulls: If you have an imbalance, or just can't "feel" one side working, go one arm at a time. This allows you to slightly rotate your torso into the pull, getting a crazy contraction.

- Underhand (Supinated) Grip: This involves more biceps, which isn't a bad thing if you want to move heavier weight. It also puts the lats in a very strong mechanical advantage.

Recovery and Volume: Don't Overcook It

The back is a massive muscle group, but it’s easy to overtrain. If you’re doing deadlifts, rows, and pull-ups all in the same session, you might be hitting a point of diminishing returns.

For most people looking for hypertrophy, 8 to 12 sets of vertical pulling per week is the "Goldilocks" zone. That’s not 12 sets of lat pulls in one day. That’s maybe 4 sets on Monday and 4 sets on Thursday.

Realistically, if you can’t control the weight on the way up, it’s too heavy. The eccentric—the part where the bar goes back up—is where a lot of the muscle damage (the good kind) happens. Don't just let the weight slam back into the stack. Count to two on the way up. Feel the lats stretching. It should almost feel like someone is pulling your arms out of their sockets at the very top. That stretch is vital.

A Note on Straps

Use them.

Seriously. People get weirdly elitist about grip strength. "If you can't hold it, you shouldn't pull it." That’s nonsense if your goal is back growth. Your back is significantly stronger than your grip. If your forearms give out at rep 8, but your lats could have done 12, you just wasted 4 reps of growth. Use Versa Gripps or basic lifting straps so you can focus entirely on the lat contraction without worrying about the bar sliding out of your sweaty palms.

Correcting the "Shrug" Habit

One thing I see constantly: people ending the rep with their shoulders hunched up by their ears. This happens because the traps are trying to help out.

📖 Related: Calories in One Cup of Spinach: Why Your Tracking App Might Be Wrong

To fix this, visualize a string pulling your chest toward the ceiling. As the bar comes down, your chest should meet it halfway. Not by leaning back, but by "opening up" your torso. This keeps the shoulders depressed and the tension exactly where it belongs.

Practical Next Steps for Your Next Workout

- Check your seat height. Ensure your feet are flat and your thighs are firmly wedged. If you’re a shorter lifter, you might need to put a couple of weight plates under your feet to reach the floor.

- Adjust your grip. Move your hands in. Try that 1.5x shoulder-width grip. Use a thumbless grip if you've been struggling with "bicep takeover."

- The "Pause" Test. On your first set, hold the bar at your chest for a full two-second count. If you can't hold it there without your form collapsing or your chest caving in, the weight is too heavy. Drop it by 10 pounds and try again.

- Film yourself from the side. This is the only way to see if you’re leaning back too far. You'll probably be surprised at how much you're actually swinging.

- Track your progress. Don't just chase weight. Chase "perfect" reps at a specific weight before moving up. If you did 100 lbs for 10 reps with a little swing last week, and 100 lbs for 10 reps with zero swing this week, you got stronger.