History is usually messy. It’s not just a series of dates or a neat line on a map; it’s a chaotic scramble of people trying to save their lives while carrying nothing but a suitcase and a few memories. When we talk about the last boat out of Shanghai, we aren't just discussing a single vessel. We’re talking about a massive, desperate exodus that fundamentally changed the demographics of the world, from the neighborhoods of San Francisco to the high-rises of Hong Kong and the suburbs of Taipei.

Most people think of 1949 as a hard stop. A door slamming shut. But the reality of the flight from Shanghai was a stuttering, terrifying process that lasted months. It was a time of hyperinflation where you needed a literal wheelbarrow of cash just to buy a loaf of bread, and yet, people were still trying to buy passage on steamships.

You’ve probably seen the photos of crowded docks. They’re haunting. People were literally climbing over each other to get onto ships like the SS Huamen or the General Gordon. Helen Zia, an incredible journalist who spent years tracking down survivors for her research, captures this beautifully in her work. She found that for many, the "last boat" wasn't just about the date—it was about the moment they realized the world they knew was gone forever.

The Chaos of 1949 and the Panic at the Bund

Shanghai in the late 1940s was "The Paris of the East," but it was a city on the edge of a nervous breakdown. The Chinese Civil War was tilting toward the Communists, and the People's Liberation Army was moving south. If you were a wealthy merchant, a student with "Western" ideas, or anyone tied to the Nationalist government, you were terrified.

The Bund—that iconic waterfront—became a scene of pure desperation.

Imagine the noise. The smell of coal smoke and river water. Thousands of people packed into the docks, clutching tickets that might be fake. Some people spent their entire life savings on a single ticket for a child, staying behind themselves because they couldn't afford a second one. It’s gut-wrenching to think about.

Money was basically useless. The Gold Yuan was crashing so fast that prices changed by the hour. If you had silver coins or American dollars, you might have a chance. If not? You were stuck. Many people tried to bribe their way onto any floating vessel, including cargo ships that weren't even meant for passengers. They slept on decks, huddled in steerage, and watched the skyline of Shanghai fade away, wondering if they’d ever see it again.

Who Were the "Shanghai 4"?

In much of the popular literature surrounding this era, historians focus on specific archetypes. Helen Zia’s research highlights four distinct types of people who fled, often referred to in historical circles as a way to understand the diaspora.

👉 See also: The Gospel of Matthew: What Most People Get Wrong About the First Book of the New Testament

There was the "daughter of a wealthy family" who had to learn how to cook and clean for the first time in her life in a tiny apartment in New York. There was the "orphan" who didn't even know their real name, swept up in the crowd. There was the "student" who thought they were leaving for a few months of study, only to be barred from returning for decades. And there was the "soldier" or "government official" who knew that staying meant a certain death sentence or "re-education."

These aren't just characters. These were real people like Bing, Annuo, Benny, and Ho. Their lives were bifurcated: the "before" in a glitzy, cosmopolitan Shanghai, and the "after" in a foreign land where they were often treated as second-class citizens.

The Ships That Changed Everything

It wasn’t just one boat. While the phrase last boat out of Shanghai suggests a singular event, it was a fleet of necessity.

- The SS Huamen: This ship is legendary in the stories of the exodus. It was packed far beyond its capacity. People were sleeping in the hallways, on top of luggage, anywhere they could find a square inch of space.

- The General Gordon: A massive American transport ship. If you could get on this, you were likely headed for the United States, but the screening process was brutal.

- Fishing Junks and Tugboats: For those who couldn't get on the big steamers, the only option was the "slow boat" to Hong Kong. These were dangerous journeys through waters often patrolled by various factions of the war.

The journey to Hong Kong was particularly significant. At the time, Hong Kong was a British colony and was suddenly flooded with hundreds of thousands of refugees. This influx is actually what fueled Hong Kong's industrial boom in the 50s and 60s. The tailors, the textile magnates, the filmmakers—they all came on those boats.

Why This History Was "Lost" for So Long

For a long time, the story of the Shanghai exodus was buried. In Mainland China, it wasn't a topic people talked about openly for decades. In the West, it was overshadowed by the Cold War and the Korean War.

It took a long time for the children and grandchildren of these refugees to start asking questions. Why doesn't Grandma talk about her childhood? Why do we have these old, fading photos of a mansion in Shanghai but we live in a one-bedroom apartment in San Francisco?

The trauma was real. Many survivors had "refugee guilt." They felt bad for leaving family members behind. Or they were so busy surviving in a new country that they didn't have time to be nostalgic. Honestly, it’s a miracle so many of these stories were preserved at all. Organizations and historians have recently been rushing to record oral histories before the last of that generation passes away.

✨ Don't miss: God Willing and the Creek Don't Rise: The True Story Behind the Phrase Most People Get Wrong

The Myth of the "Clean Break"

There’s this misconception that everyone who left was a "millionaire." That’s just not true. While the elite certainly had a better chance of getting out, plenty of middle-class families and even poor laborers managed to scramble onto boats.

Also, the "break" wasn't clean.

Many people stayed in Hong Kong for years, waiting for the political winds to change so they could go home. They didn't unpack their bags. They lived in makeshift shacks or crowded tenements, always looking back toward the mainland. It was only when it became clear that the new government was there to stay that they finally moved on to the U.S., Canada, or Australia.

Life After the Boat

What happened when the boats docked? It wasn't always a warm welcome.

Refugees arriving in the U.S. faced the tail end of the Chinese Exclusion Act's cultural hangover and the rising "Red Scare." Even if you were fleeing Communism, you were still viewed with suspicion because you were from a Communist country. It was a bizarre, "no-win" situation.

In Taiwan, the arrival of millions of mainlanders created a complex social dynamic that still influences Taiwanese politics today. The "Mainlanders" vs. the "Local Taiwanese" is a divide that started right there on those docks in 1949.

How to Trace This History Today

If you suspect your family was part of the last boat out of Shanghai era, there are ways to dig into it. It’s not easy, but it’s possible.

🔗 Read more: Kiko Japanese Restaurant Plantation: Why This Local Spot Still Wins the Sushi Game

- Check the Ship Manifests: Archives like the National Archives (NARA) in the U.S. have passenger arrival records. Look for ships coming from Hong Kong or Shanghai between 1948 and 1952.

- The Shanghai Municipal Archives: While difficult to access from abroad, they hold records of the city's administration during the transition.

- Oral History Projects: Look into the "1949 Project" and similar initiatives that have cataloged interviews with survivors.

- Look for Old Passports: Many families kept their "Republic of China" passports issued in Shanghai. These are goldmines of information, often containing exit and entry stamps that provide a timeline of the journey.

Practical Steps for History Buffs and Researchers

If you're looking to dive deeper into this specific moment in time, don't just stick to general history books. You need the granular stuff.

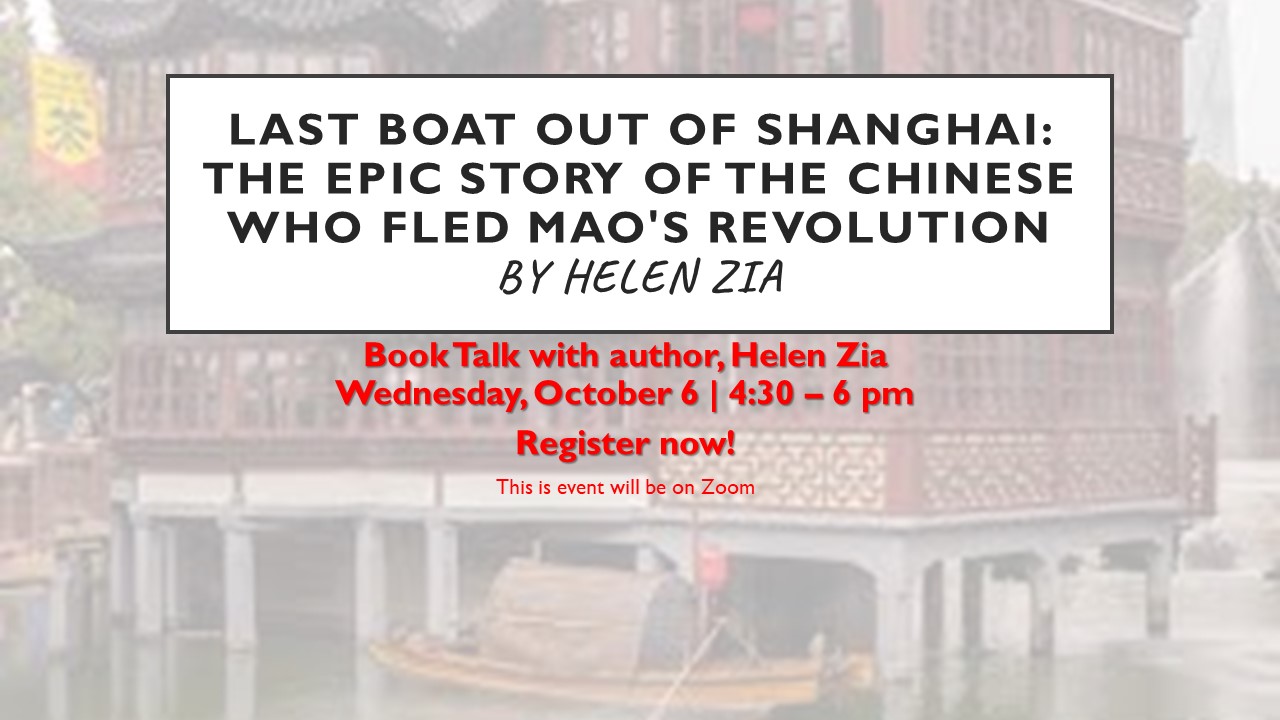

First, read Last Boat Out of Shanghai by Helen Zia. It is the definitive text on the personal human cost of the exodus. She spent twelve years interviewing people, and it shows. The nuances of how people hid jewelry in their hair or how they used code words in letters are all there.

Second, look at the photography of Jack Birns. He was a Life magazine photographer who was in Shanghai in 1947 and 1948. His photos of the gold rushes and the crowds at the docks give you a visual sense of the panic that words can't quite capture.

Lastly, visit the museums in Hong Kong or the Overseas Chinese Museum in various cities. They often have exhibits specifically dedicated to the 1949 migration.

This isn't just "Chinese history." It's a global story of migration, survival, and the incredible resilience of the human spirit. When everything you own is stripped away and you're standing on the deck of a rusting ship, what do you keep? You keep your stories. And those stories are what we have left today.

To truly understand the modern world—the tech hubs of Silicon Valley, the finance centers of Hong Kong, the very fabric of the Chinese diaspora—you have to understand what happened on those docks. It was the end of one world and the chaotic, painful birth of another. No matter how much time passes, the legacy of that final departure remains a foundational pillar of the 20th century.