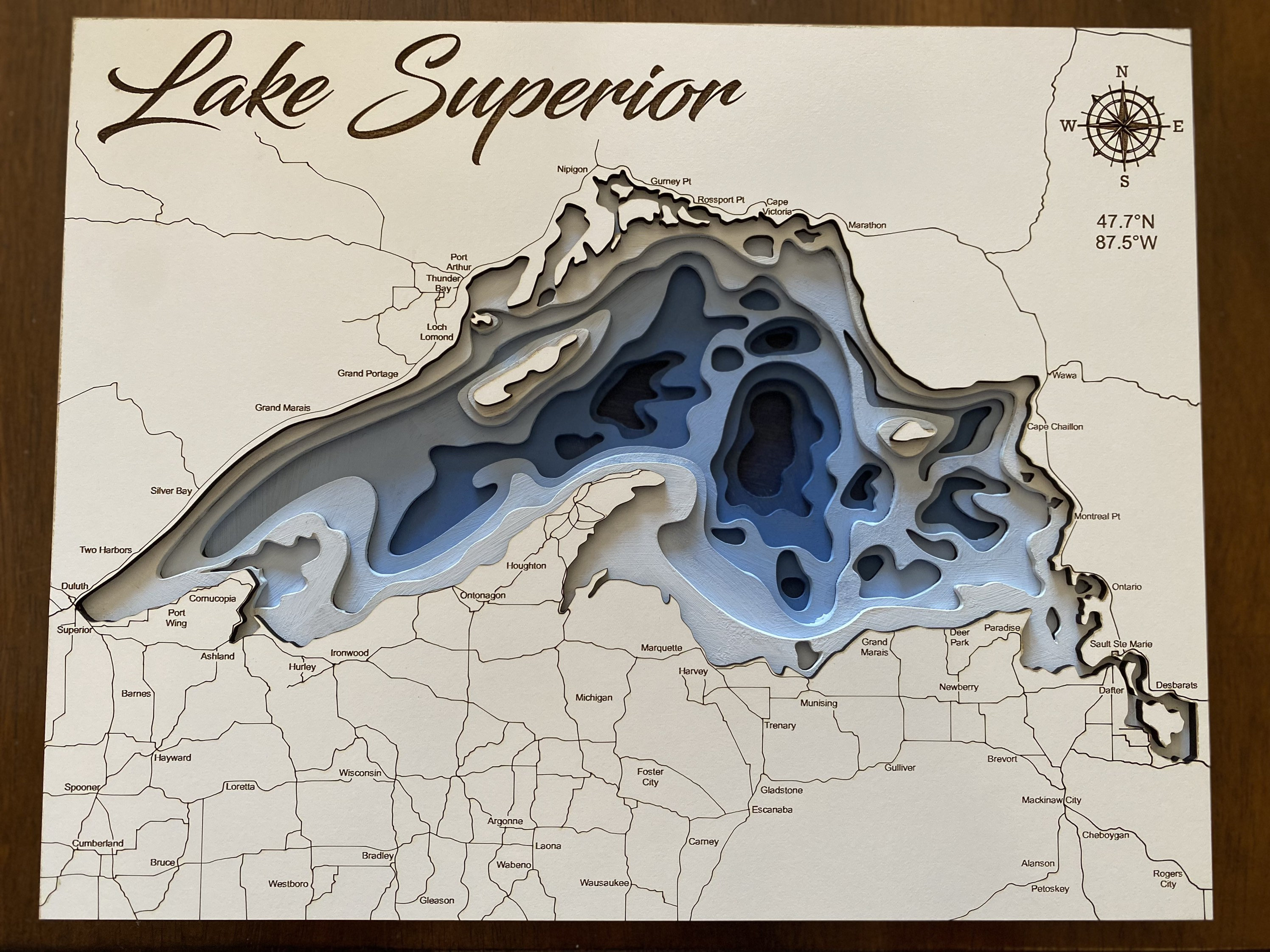

It is huge. Seriously. If you’ve ever stood on the shore at Pictured Rocks or looked out from Brighton Beach in Duluth, you know that feeling where the horizon just sort of... vanishes. You're looking at 10% of the world’s surface freshwater. But the surface is a lie. The real story is the lake superior map depth, a jagged, cold, and surprisingly complex underworld that keeps most of its secrets hidden under several hundred feet of tea-colored water.

People usually think of lake bottoms as giant bowls. Smooth, sandy, sloping gently toward the middle.

Lake Superior laughs at that idea.

The bathymetry of this lake—basically the underwater version of topography—is a violent mess of deep trenches, massive ridges, and vertical drops that would make a mountain climber nervous. If you drained the water tomorrow, you wouldn't see a basin; you’d see a rugged mountain range that makes the surrounding Midwest look like a pancake.

The 1,333-Foot Reality Check

Let’s talk about the "Big Number." Most people who look up a lake superior map depth are searching for that one specific spot: the deepest point. It’s located about 40 miles north of Munising, Michigan. It hits 1,333 feet (406 meters).

That is deep. For context, the Empire State Building is about 1,454 feet tall. If you dropped it into the deepest part of the lake, just the tip of the antenna would be poking out of the waves.

But here is the thing that messes with your head: the surface of Lake Superior is about 600 feet above sea level. This means the bottom of that 1,333-foot hole is actually hundreds of feet below the level of the Atlantic Ocean. Geologists call this a cryptodepression. It’s a fancy word for a hole so deep it goes "negative" relative to the rest of the planet’s oceans.

Why the eastern basin is a different beast

If you look at a high-resolution sonar map, you'll notice the lake is basically split into two personalities. The western half, near Duluth and the Apostle Islands, is relatively shallow and consistent. Then you hit the Keweenaw Peninsula. Once you wrap around that "copper thumb" of Michigan, the floor just falls out.

🔗 Read more: Floating Lantern Festival 2025: What Most People Get Wrong

The eastern basin is where the drama happens. This area is defined by "The Valleys." These are massive, north-south oriented trenches carved out by glaciers that acted like giant rasps. Some of these valleys are deeper than the Grand Canyon if you measure from the surrounding underwater "peaks."

The Mystery of the Caribou Island Trench

One of the most fascinating features on any modern lake superior map depth readout is the area around Caribou Island. This isn't just a deep spot; it’s a graveyard.

The "Three Sisters" are a series of massive rogue waves that are legendary in Superior lore, often blamed for sinking the SS Edmund Fitzgerald. But those waves are born from the lake's depth. When a massive storm surges across the open water and hits a sudden change in depth—like the steep ridges near Caribou Island—the energy has nowhere to go but up.

Most people don't realize how fast the depth changes here. You can go from 100 feet of water to 700 feet in the blink of an eye. This underwater "cliff" creates massive turbulence during November gales. It’s not just the wind; it’s the lake floor fighting the water.

- The deepest point: 1,333 feet (406m).

- Average depth: About 483 feet (147m).

- The "Deep Hole": Located at 47° 19'N, 86° 02'W.

- Water volume: 3 quadrillion gallons. Enough to cover North and South America in a foot of water.

Honestly, the sheer volume is hard to grasp. If you poured Lake Superior out, it would take nearly 200 years to refill it via the current rivers and streams that feed it. It’s a slow-moving, deep-seated giant.

Sonar Technology and the "New" Maps

We used to measure depth by dropping a lead weight on a string. It was called "sounding." Unsurprisingly, we missed a lot.

Today, organizations like the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory (GLERL) use multibeam echo sounders. Instead of one "ping," they send out a fan of sound. This has revealed things we never knew existed.

💡 You might also like: Finding Your Way: What the Tenderloin San Francisco Map Actually Tells You

For instance, there are massive "furrows" on the lake floor. These look like giant plow marks. They were caused by icebergs dragging along the bottom at the end of the last ice age. Imagine an iceberg so heavy and deep it can gouge a trench into the bedrock 500 feet below the surface.

The Mid-Lake Plateau

There’s a spot called Superior Shoal. On a lake superior map depth chart, it looks like a mountain peak rising out of nowhere. It comes within 20 feet of the surface, right in the middle of the lake.

Think about that. You are in the middle of a freshwater sea, hundreds of miles from shore, with 1,000 feet of water under your boat. Then, suddenly, there’s a rock just 20 feet down. It’s a ship-killer. It wasn't even officially "discovered" and mapped until 1929. Before then, ships just disappeared, and nobody knew why.

Why the Temperature Stays Deadly

The depth determines the temperature. Because the lake is so incredibly deep, it has massive "thermal inertia." It takes a lot of energy to heat up 3 quadrillion gallons.

Below about 200 feet, the water stays a constant 39°F (4°C).

This is the temperature where water is at its densest. It’s also why the lake "doesn't give up her dead." In shallower, warmer lakes, bacteria in a body will produce gas, causing it to float. In Superior’s deep trenches, it’s a refrigerator. The bacteria can't grow. The depth preserves everything—ships, cargo, and unfortunately, sailors—in a state of eerie, cold suspension.

Navigating the Contours

If you’re a fisherman or a diver, the lake superior map depth isn't just trivia. It’s a survival guide.

📖 Related: Finding Your Way: What the Map of Ventura California Actually Tells You

Lake trout, for example, love the "humps." These are underwater hills where the depth rises from 300 feet to 100 feet. The currents push baitfish against these walls, creating a buffet. If you can't read a bathymetric chart, you’re just wandering in a blue desert.

But for the rest of us? The depth is a reminder of how small we are.

We look at the surface and see a reflection of the sky. But underneath is a landscape of basalt and granite, carved by miles of ice, holding secrets that are literally out of reach for all but the most advanced ROVs (Remotely Operated Vehicles).

How to use depth data for your next trip

Don't just look at a paper map. If you're heading out, use digital layers. Apps like Navionics or the NOAA Chart Display Service allow you to toggle "Safety Depths."

- Avoid the "Wall": If you’re in a small craft, stay away from areas where contour lines are tightly packed. This indicates a "drop-off" where wave action can become unpredictable.

- Respect the 400-foot line: Once you cross this threshold, you are in the "Big Blue." The water behavior changes. The wind has more "fetch," meaning it can build bigger waves over the deep water than it can near the shore.

- Check the shoals: Even if you aren't a sailor, looking at a map of Superior Shoal or the Stannard Rock Light (the "loneliest place in the world") gives you a sense of the lake's jagged teeth.

Superior is beautiful, but it’s a cold, deep machine. The more you study the lake superior map depth, the more you realize that the shore is just the beginning. The real Lake Superior is the one you can’t see, stretching down into the dark, hundreds of feet below the level of the sea.

To truly understand this lake, stop looking at the horizon. Look at the soundings. The numbers tell a story of ice, pressure, and time that makes the surface look like a thin, fragile veil.

Actionable Insights for Lake Explorers:

- Download high-resolution bathymetry: Use the NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) website to view 1-meter resolution maps of specific harbors.

- Monitor the "Thermal Bar": In late spring, watch for the temperature difference between the shallow shore and the deep center; this creates a physical barrier that traps sediment and nutrients.

- Safety First: If you are boating, remember that Superior's depth means "near-shore" isn't always "shallow." Deep-water waves can hit the coastline with nearly 100% of their open-lake energy.