It is a massive, cold, inland sea. That is the only way to describe it. If you stand on the shore at Pictured Rocks or look out from the rugged cliffs of the Sleeping Giant in Ontario, the scale hits you like a physical weight. Most people know it’s big—the largest freshwater lake in the world by surface area—but when you start talking about the deepest part of Lake Superior, the conversation usually shifts from "pretty scenery" to "terrifying physics."

The water is heavy. It's dark. Down at the bottom, it's roughly 39°F (4°C) year-round. Basically, it’s a giant refrigerator that never turns off.

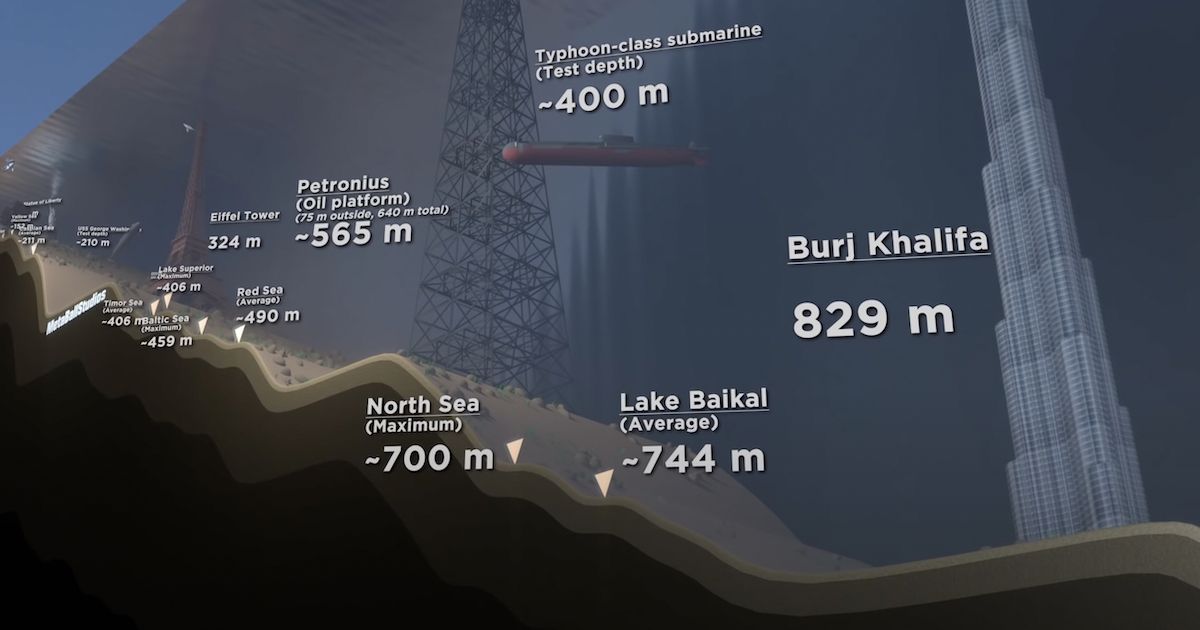

The official number you’ll see in most textbooks is 1,333 feet. That is the maximum depth. But numbers on a page don’t really capture the reality of what’s happening in the bathymetry of the Lake Superior basin. We are talking about a hole in the earth so deep that if you dropped the Empire State Building into it, the tip of the antenna would still be submerged under nearly 100 feet of water.

Finding the Deepest Part of Lake Superior

Where is it, exactly? It isn’t in the middle. Most people assume the deepest point would be dead-center, but geography is rarely that symmetrical. The deepest part of Lake Superior is actually located about 40 miles off the coast of Munising, Michigan.

Specifically, it’s in a place called the Caribou Basin.

This isn't just a gentle slope. The lake floor is a chaotic landscape of trenches, ridges, and valleys carved out by massive glacial movements thousands of years ago. When the Laurentide Ice Sheet retreated, it didn't just melt away politely; it gouged the earth. The Caribou Basin is the result of that raw geological power.

Some people get confused between the average depth and the maximum depth. Honestly, the average depth is only about 483 feet. That's still deep, but the jump to 1,333 feet is where things get interesting for researchers and explorers.

🔗 Read more: City Map of Christchurch New Zealand: What Most People Get Wrong

Why the depth matters for shipwrecks

The depth is why Lake Superior "never gives up her dead," as the famous Gordon Lightfoot song goes. It’s not just poetry. It’s limnology. Because the water is so cold and the lake is so deep, bacteria that would normally cause a body to bloat and float to the surface can’t thrive. Down at the deepest points, the pressure and temperature act as a natural preservative.

Look at the SS Edmund Fitzgerald.

It sits in about 530 feet of water. That isn’t even close to the deepest part of the lake, yet it was deep enough to keep the wreck largely intact and the crew unreachable for decades without highly specialized equipment. If a ship were to go down in the Caribou Basin at 1,333 feet, it would be entering a zone where the pressure is over 570 pounds per square inch.

The Mystery of the 1985 Submarine Descent

For a long time, we only knew about the bottom through sonar. Then came 1985. A man named Dr. J. Val Klump became the first person to actually reach the deepest part of Lake Superior in a submersible. He used a research vessel called the Johnson Sea-Link II.

It wasn't just a stunt.

Klump and his team were looking for life. You’d think that at 1,333 feet, in total darkness and near-freezing temperatures, nothing would be happening. You’d be wrong. They found signs of life—small crustaceans, worms, and even certain types of fish like the deepwater sculpin that have adapted to live in a high-pressure, low-light environment.

💡 You might also like: Ilum Experience Home: What Most People Get Wrong About Staying in Palermo Hollywood

The bottom isn't just sand, either. It’s a fine, silty clay.

When the sub touched down, it kicked up "marine snow"—bits of organic material drifting down from the surface. It’s a slow-motion world. Everything moves differently down there. Scientists have used these deep-trench explorations to understand how carbon cycles through the Great Lakes, which actually helps us understand global climate patterns.

Is there anything deeper?

There are always rumors. Some local fishermen and amateur sonar enthusiasts claim they’ve seen "pings" that suggest holes deeper than 1,333 feet. Maybe 1,350? Maybe more?

Technically, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) sticks to the 1,333 figure. However, bathymetric mapping is an ongoing process. We have better maps of the surface of Mars than we do of the entire floor of Lake Superior. It is entirely possible that a narrow fissure or a small depression exists that hasn't been officially logged yet. But for now, the Caribou Basin holds the crown.

Comparison to Other Great Lakes

To understand the scale of the deepest part of Lake Superior, you have to look at its siblings. Lake Erie is the shallowest, with a maximum depth of only about 210 feet. You could stand five Lake Eries on top of each other and still not reach the bottom of Superior’s deepest trench.

- Lake Michigan: 923 feet

- Lake Ontario: 802 feet

- Lake Huron: 750 feet

Superior is the outlier. It holds more water than all the other Great Lakes combined, plus three extra Lake Eries for good measure.

📖 Related: Anderson California Explained: Why This Shasta County Hub is More Than a Pit Stop

The sheer volume of water creates its own weather. Because the deepest parts of the lake hold so much thermal mass, Lake Superior rarely freezes over completely. The "deep" stays relatively warm compared to the surface in the winter, and relatively cool in the summer. It acts as a massive heat sink that regulates the climate of the entire Upper Peninsula and parts of Ontario.

Navigating the Depths: What You Should Know

If you’re planning on visiting or even just obsessing over the lake’s geography, there are some practical realities to grasp.

First, don't expect to see the bottom. Even in the clearest parts of Superior, where visibility can reach 70 feet or more, the deepest part of Lake Superior is shrouded in absolute, permanent "midnight zone" darkness. Sunlight doesn't make it much past 200 to 300 feet in these waters.

Second, the lake is dangerous. People often treat it like a big pond, but the depth contributes to "rogue waves." When you have a massive fetch (the distance wind travels over water) and deep water that suddenly hits a shallower shelf, the energy has nowhere to go but up. This creates waves that have swallowed ships 700 feet long.

Actionable insights for Great Lakes enthusiasts

- Visit the Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum: Located at Whitefish Point, it gives you a terrifyingly good look at what happens when the lake's depth and power collide with human engineering.

- Check NOAA Bathymetry Maps: If you are a geek for charts, NOAA offers high-resolution digital terrain models. You can virtually "fly" through the Caribou Basin and see the ridges that define the deepest points.

- Respect the Temperature: Even in July, if you fall into deep water, the "cold shock response" is a real killer. The surface might be 60°F, but 10 feet down it drops fast. Always wear a PFD.

- Monitor the Lake Superior Lakewide Action and Management Plan (LAMP): This is where the real science happens. They track the health of the deep-water ecosystems and how invasive species like the quagga mussel are moving into deeper territories.

The deepest part of Lake Superior is more than just a trivia point. It is a biological vault, a graveyard, and a massive thermal engine that keeps the heart of the Midwest beating. It’s a place where humans aren't meant to go, but we can't stop ourselves from looking.

If you want to truly appreciate it, take a boat out a few miles from the Keweenaw Peninsula. Turn off the engine. Look down. Realize there is a quarter-mile of water beneath your feet. That silence is the heaviest thing in the world.

To stay informed on the shifting ecology of these depths, keep an eye on the latest bathymetric surveys from the University of Minnesota Duluth’s Large Lakes Observatory. They are the ones currently pushing the boundaries of what we know about the world at 1,333 feet down.