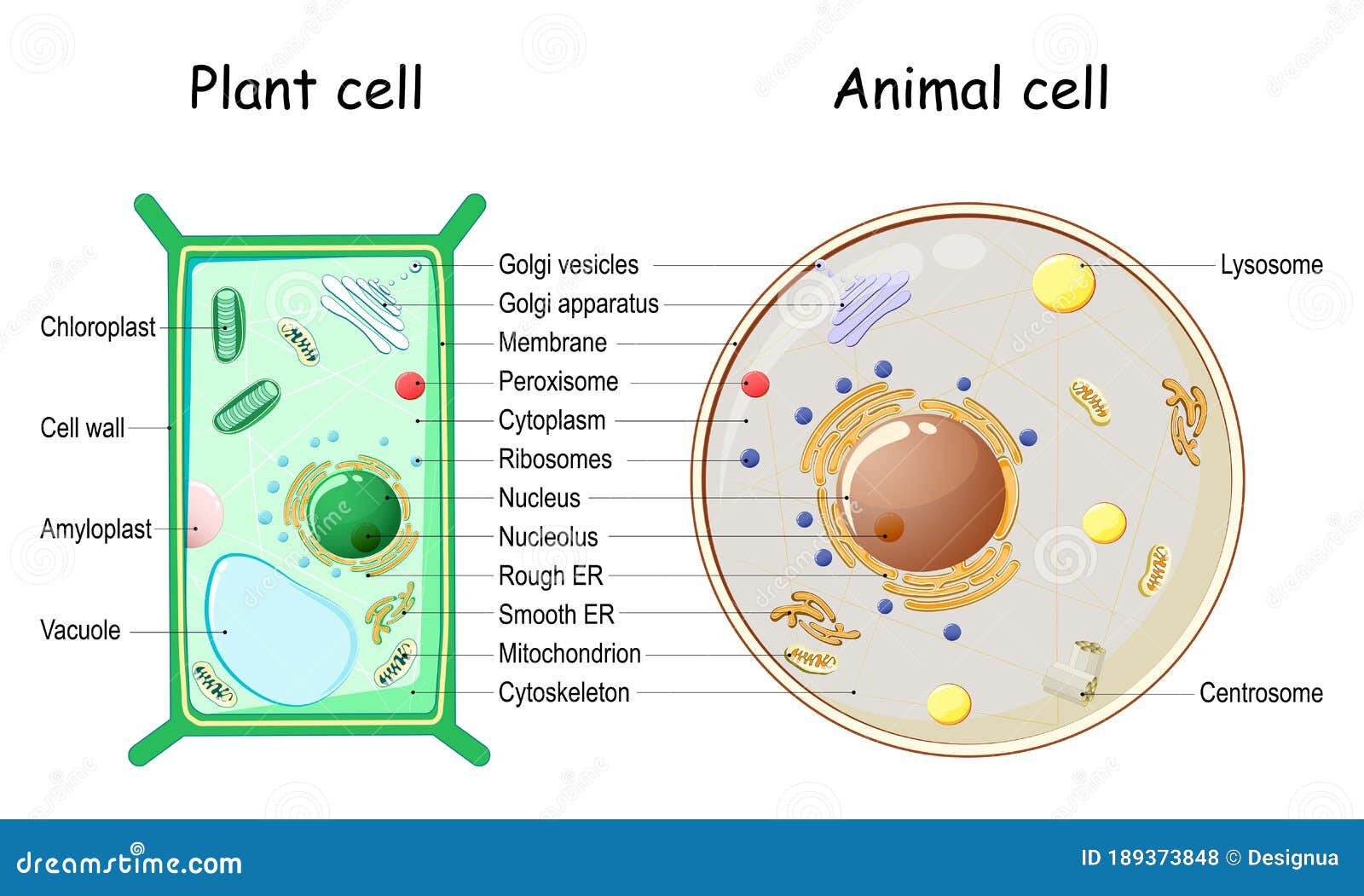

You probably remember squinting through a plastic microscope in seventh grade, trying to find a smudge that looked like a fried egg. That smudge was a cell. It’s the basic building block of every living thing, from the moss on a damp rock to the person reading this screen right now. But when you look at a labelled plant cell and animal cell side-by-side, you aren't just looking at biology homework. You’re looking at the fundamental split in how life on Earth decided to survive. One builds towers of wood; the other grows muscles and nerves.

It’s easy to think of them as basically the same thing with a few different parts thrown in. Honestly, they share a lot. Both have a nucleus—the "brain" or "hard drive" containing DNA. Both have mitochondria, which are famously the powerhouse of the cell (thanks, memes). But the differences are where things get weird and interesting.

The Rigid Walls vs. The Squishy Borders

The most obvious thing you’ll notice on any diagram is the shape. Plant cells look like bricks. They are rectangular, sturdy, and stacked. Animal cells? They’re basically blobs. Irregular, roundish, and flexible.

This isn't an accident. Plants don't have skeletons. A 300-foot redwood tree stays upright because every single cell is encased in a cell wall made of cellulose. It’s like a tiny wooden crate. If you’ve ever crunched into a fresh piece of celery, you’re literally snapping those cell walls. Animal cells don’t have this. Instead, we have a cell membrane. It’s thin and oily. This allows our cells to move, stretch, and specialize into things like red blood cells that squeeze through tiny capillaries. If our cells had walls, we’d be as stiff as a board.

Solar Panels and Trash Cans

If you look at a labelled plant cell and animal cell under a high-powered electron microscope, you’ll see some "extras" in the plant version that just don’t exist in ours. The biggest one is the chloroplast. These are the little green jellybeans that perform photosynthesis. They take sunlight and turn it into sugar. Humans can't do this, which is why we have to eat lunch instead of just standing in the sun.

Then there's the vacuole. Now, animal cells do have vacuoles, but they’re tiny and temporary—mostly for moving waste around. In a plant cell, the central vacuole is massive. It can take up 90% of the cell's volume. It’s a giant water balloon. When a plant is well-watered, this balloon pushes against the cell wall, making the plant stand tall. When you forget to water your houseplant and it wilts, it’s because those vacuoles have deflated.

The Stuff They Both Share (The Complex Interior)

We shouldn't ignore the similarities, because they are incredibly complex. Both cell types are eukaryotic. This means they have "membrane-bound organelles." Think of these like separate rooms in a house, each with a specific job.

- The Nucleus: This is where the blueprints (DNA) live. It’s protected by a double membrane.

- Ribosomes: These are the workers. They sit on the Endoplasmic Reticulum and churn out proteins.

- Golgi Apparatus: Basically the post office. It takes proteins, packages them into little bubbles called vesicles, and sends them where they need to go.

- Cytoplasm: The jelly-like goo that fills the space. It’s not just water; it’s a crowded soup of chemicals and structures.

What about Lysosomes?

Here is a nuance that often trips people up. For a long time, textbooks said only animal cells have lysosomes (the "suicide bags" that digest waste). Modern research has shown that some plants have lysosome-like vacuoles that do the same thing. Nature doesn't always follow the neat lines we draw in textbooks. Dr. Jennifer Lippincott-Schwartz, a renowned cell biologist, has done extensive work showing how these organelles move and interact in real-time. It’s way more chaotic and dynamic than a static diagram suggests.

Centrioles: The Animal Cell Secret

When it’s time for a cell to divide, animal cells use something called centrioles. These look like little bundles of pasta. They help organize the "scaffolding" that pulls DNA apart into two new cells. Most higher plants don't have these. They manage to divide just fine without them, using a different method to build a new cell wall right down the middle. It's a different solution to the same problem: how to make two out of one.

Why You Should Care About These Labels

Understanding the labelled plant cell and animal cell isn't just for passing a test. It’s the foundation of modern medicine and agriculture. When scientists develop a new herbicide to kill weeds, they often target the cell wall or the chloroplast. Why? Because humans don't have those. If the poison only attacks things specific to plant cells, it won't hurt the person spraying it (ideally).

On the flip side, many viruses target specific proteins on the cell membranes of animal cells. Because plant cells have that thick wall, they are often immune to the same viruses that make us sick.

Spotting the Differences: A Quick Mental Checklist

If you’re looking at a diagram and can’t tell which is which, look for these "tell-tale" signs:

- Shape: Is it a neat rectangle? Probably a plant. Is it a messy circle? Probably an animal.

- Color: If you see green spots (chloroplasts), it’s a plant.

- The Big Bubble: A giant empty-looking space in the middle is the central vacuole. That’s a plant hallmark.

- The Border: Does it have a thick, double-layered outline? That’s the cell wall.

Common Misconceptions

People often think animal cells are "more advanced." That’s not really true. Plant cells are arguably more self-sufficient. They make their own food! They also have to survive extreme weather, whereas animals can just move to the shade or find a burrow. Plant biology is an incredible feat of structural engineering and chemical synthesis.

Another weird one? Some people think only animals have DNA. Nope. Every living cell—plant, animal, fungi, or bacteria—uses DNA. In both plant and animal cells, that DNA is tucked away inside the nucleus.

How to Study Cell Biology Effectively

Don't just stare at a static image. The best way to understand these structures is to draw them yourself. Start with the "generic" parts like the nucleus and mitochondria. Then, "upgrade" one to a plant cell by adding the wall and the chloroplasts.

💡 You might also like: iPad Pro 12.9 6th Generation Case: What Most People Get Wrong

Actionable Next Steps

- Get Hands-on: If you have access to a basic microscope (even a cheap one for kids), peel a thin layer of onion skin. That’s a plant cell. Use a toothpick to gently scrape the inside of your cheek. Those are animal cells.

- Use 3D Models: Virtual reality and AR apps now let you "walk through" a cell. Seeing the scale of a vacuole compared to a nucleus in 3D makes it much easier to remember.

- Focus on Function: Instead of memorizing names, ask "What does this part do?" If you know the Golgi Apparatus is the shipping center, you'll never forget what it looks like (a stack of pancakes/boxes).

- Check the Latest Research: Follow journals like Cell or Nature (the "News" sections are usually readable). We are still discovering new things about how the "cytoskeleton"—the internal framework of the cell—helps things move around.

Biology is messy. It's tiny machines working in a soup of chemicals to keep you alive. Whether it's the oak tree in your yard or the dog on your couch, it all comes down to these microscopic rooms and how they are built.