Sharks are basically the perfect biological machines. If you look at a labelled diagram of shark anatomy, you aren’t just looking at a fish; you’re looking at 400 million years of evolutionary fine-tuning. Most people think they’re just teeth and grit. They aren't. They are sensory powerhouses that can literally feel the electricity in your heartbeat.

It’s weird. We spend so much time fearing them, yet most of us couldn't point out the difference between a pectoral fin and a pelvic fin if our lives depended on it. Honestly, understanding how these animals are built is the first step toward respecting them instead of just being terrified of them.

The Exterior: More Than Just a Grey Tube

When you first glance at a labelled diagram of shark structures, the fins are what jump out. But look closer at the skin. It’s not smooth like a dolphin. It’s covered in dermal denticles. These are essentially tiny teeth growing out of their skin. If you pet a shark from head to tail, it feels like silk. Go the other way? It’ll shred your hand like 40-grit sandpaper. This reduces drag, allowing predators like the Shortfin Mako to hit speeds over 45 mph.

The Fins and Why They Matter

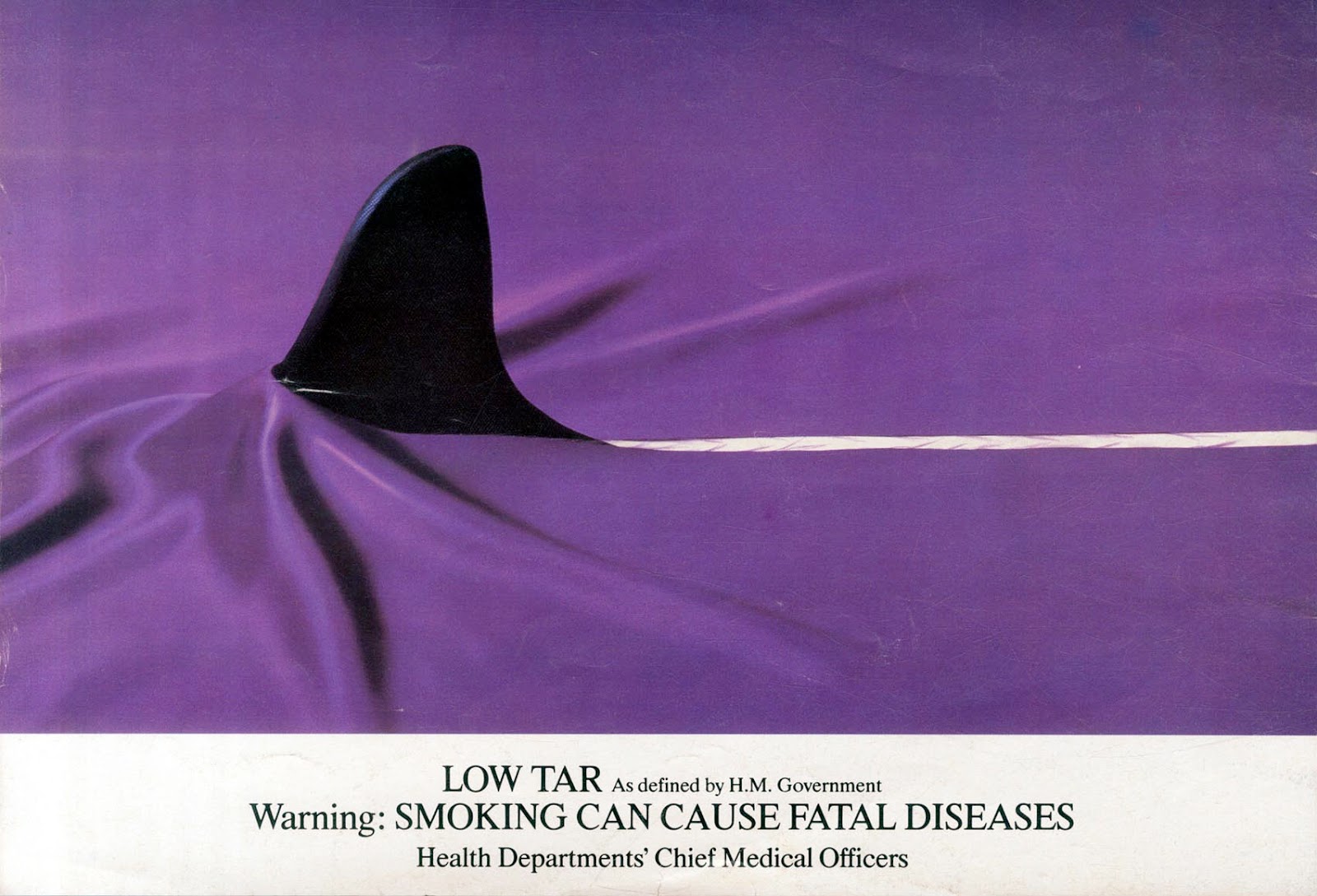

Most diagrams highlight the Dorsal Fin first. That’s the classic "Jaws" triangle. It’s for stability. Without it, the shark would just barrel roll through the water like a loose log. Then you have the Pectoral Fins. Think of these as the wings of an airplane. Sharks can’t swim backward. They don't have the bony rays that let a goldfish back out of a corner. They use these side fins to create lift. If a shark stops swimming, many species literally sink.

Then there’s the Caudal Fin, or the tail. This is the engine. In a Great White (Carcharodon carcharias), the upper and lower lobes are nearly symmetrical, which is great for power. In a Thresher shark, that top lobe is massive—sometimes as long as the shark itself—used to whip and stun schools of fish. It's a specialized tool, not just a flipper.

📖 Related: Coach Bag Animal Print: Why These Wild Patterns Actually Work as Neutrals

The Sensory Array: A Biological Supercomputer

This is where a labelled diagram of shark anatomy gets genuinely sci-fi. Near the snout, you’ll see tiny black pores. These are the Ampullae of Lorenzini. They are jelly-filled tubes that detect electromagnetic fields. Every time a fish twitches a muscle, it sends out a tiny electrical pulse. The shark feels that. Even if a stingray is buried under a foot of sand in total darkness, the shark "sees" the electricity.

Then there is the Lateral Line. It’s a faint stripe running down the side of the body. It’s basically a long-distance ear that feels vibrations in the water. It lets the shark know exactly where a struggling prey item is from hundreds of yards away.

The Gills: Breathing While Moving

Most fish have an operculum—a bony flap that pumps water over their gills. Sharks don’t have that. They have 5 to 7 Gill Slits. Many sharks are "obligate ram ventilators." This sounds fancy, but it just means they have to keep their mouths open and keep moving to breathe. If they stop, they suffocate.

However, if you look at a diagram of a bottom-dwelling shark like a Nurse shark, you'll see a small hole behind the eye called a Spiracle. This allows them to pull in oxygenated water while they’re sitting still on the seafloor. It’s a neat workaround for a sedentary lifestyle.

👉 See also: Bed and Breakfast Wedding Venues: Why Smaller Might Actually Be Better

The Interior: No Bones About It

Here is the kicker: Sharks have zero bones. Their entire skeleton is made of cartilage. It’s the same stuff in your nose and ears. This makes them lighter and more flexible. On a labelled diagram of shark internal organs, you’ll notice the Liver is massive. It can take up to 25% of their body weight. Since sharks don't have a swim bladder (the air sac most fish use to float), they rely on a liver packed with oil to stay buoyant. Oil is lighter than water. Without that oily liver, they'd drop to the bottom like a stone.

The stomach is also pretty wild. If a shark eats something it can’t digest—like a turtle shell or, occasionally, human trash—it can perform "gastric eversion." It literally barfs its entire stomach out of its mouth, rinses it in the ocean, and pulls it back in. Hard to find that on a basic classroom poster, but it’s a real part of their survival kit.

Why Accuracy in Diagrams Matters

You see a lot of generic "fish" diagrams labelled as sharks. That’s a mistake. Sharks have Claspers if they are male—external appendages used for mating—which you won't find on a standard tuna. They also have a Spiral Valve in their intestine. Instead of a long, loopy gut like ours, theirs is a tight spiral staircase. This maximizes nutrient absorption in a very short space.

Researchers like Dr. Neil Hammerschlag have spent years mapping these physiological traits to understand how sharks handle the stress of catch-and-release fishing. When a shark is fought too long, its blood chemistry changes. Its "internal diagram" starts to break down due to lactic acid buildup. Knowing where the vital organs sit helps biologists draw blood samples or tag sharks without causing permanent damage.

✨ Don't miss: Virgo Love Horoscope for Today and Tomorrow: Why You Need to Stop Fixing People

Common Misconceptions in Shark Anatomy

- They have to swim or they die: Only some species. Many, like the Wobbegong, are perfectly happy sitting still.

- They have "rows" of teeth: Yes, but they aren't fixed. They are on a conveyor belt. A shark can go through 35,000 teeth in a lifetime.

- They are mindless eaters: Their brain-to-body mass ratio is actually comparable to some birds and mammals. They have complex social structures and can learn tasks.

Actionable Insights for the Aspiring Naturalist

If you are looking at a labelled diagram of shark anatomy for a project or just out of curiosity, focus on the "Form follows Function" rule. A shark with a flat head (like a Hammerhead) uses that shape as a bow plane for better turning and as a giant sensory metal detector. A shark with a long, thin body is likely an open-ocean cruiser.

To truly understand shark anatomy:

- Compare the tail shapes: Learn to distinguish between the symmetrical tail of a cruiser and the asymmetrical tail of a bottom-dweller.

- Look for the spiracle: This tells you immediately if the shark is a "ram ventilator" or a "stationary breather."

- Check the fin placement: Note how the second dorsal fin is often much smaller and sits far back near the tail.

- Identify the snout pores: Realize those tiny dots are the most advanced sensors in the ocean.

Understanding these biological markers changes how you see these animals. They aren't monsters; they are highly specialized, cartilaginous masterpieces that have survived five mass extinctions. Next time you see a diagram, look for the spiral valve or the ampullae. That’s where the real magic happens.