You’ve seen them in every doctor's office. Those plastic, slightly yellowed models standing in the corner. We usually call him "Stan" or "Skully." But when you actually start looking at labeled parts of a skeleton, things get complicated fast. Most people think they know the basics. You have a skull, some ribs, and a spine. Simple, right? Honestly, it’s a mess in there.

Evolution didn't design us to be "clean." It’s a series of biological hacks. Your skeleton is a living, breathing organ system that swaps out its entire cellular makeup every decade or so. If you're looking at a diagram and it just says "Arm Bone," you're missing the weird reality of how 206 bones actually keep you upright without collapsing into a heap of meat.

The Skull is Not One Bone (And Other Lies)

Look at any basic diagram. It points to the head and says "Skull." That’s like pointing at a car and just saying "Metal." The human cranium is a jigsaw puzzle of 22 different bones. Most of them are fused together by these wiggly lines called sutures. If you’re a baby, these bones are actually floating. It’s why infants have "soft spots." We need that flexibility so the head can actually fit through the birth canal without causing a total disaster.

The mandible is the only one that really moves. It’s your jaw. Everything else, from the frontal bone at your forehead to the occipital bone at the very back, is locked tight. But here is where it gets weird. Deep inside your ear are the smallest labeled parts of a skeleton you’ll ever find: the malleus, incus, and stapes. People call them the hammer, anvil, and stirrup. Without these tiny fragments of calcium, you’re deaf. They vibrate against each other to translate air movement into sound. It’s absurdly delicate.

The Axial Skeleton: Your Central Command

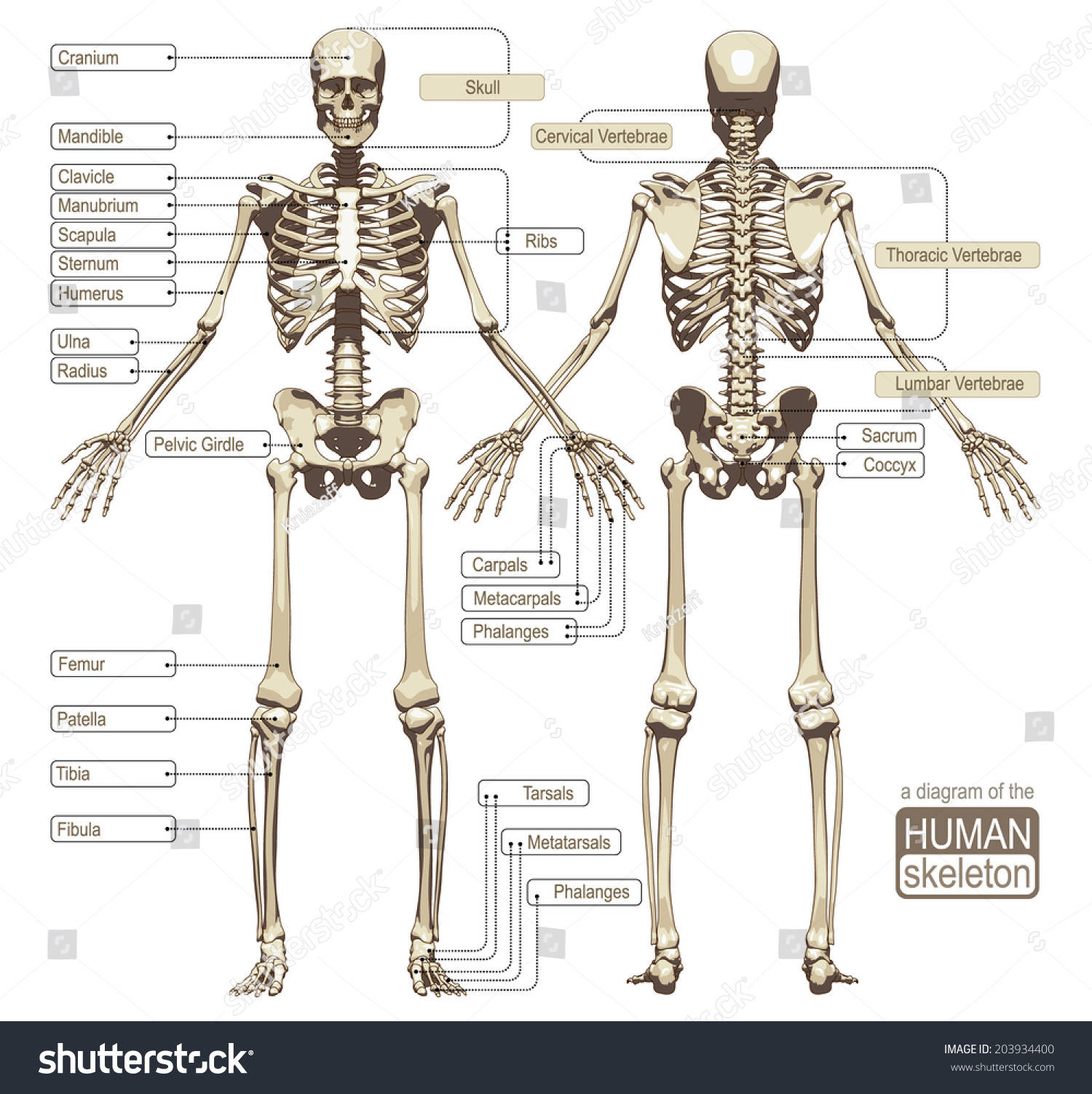

Think of your body like a skyscraper. The axial skeleton is the steel beam running right down the middle. It’s the core. You’ve got the vertebral column, the rib cage, and the skull.

Most people mess up the spine. They think it's just a stack of blocks. It’s actually divided into very specific regions. You have seven cervical vertebrae in your neck. Fun fact: a giraffe also has seven cervical vertebrae. Theirs are just way bigger. Then you hit the thoracic section where the ribs attach, and finally the lumbar—the thick, chunky bones in your lower back that take all the heat when you lift a box the wrong way.

The ribs are even weirder. You have "true" ribs, "false" ribs, and "floating" ribs. The floating ones don't even attach to your sternum at the front. They just sort of hang out at the bottom, protecting your kidneys. If you’ve ever had a "bruised rib," you know that even a tiny hairline fracture in these thin strips of bone makes breathing feel like you’re being stabbed with a butter knife.

💡 You might also like: Medicine Ball Set With Rack: What Your Home Gym Is Actually Missing

The Appendicular System: Why You Can Actually Move

This is the "extra" stuff. Your arms, your legs, and the "girdles" that connect them. The scapula (shoulder blade) is one of the most fascinating labeled parts of a skeleton because it doesn't actually "bolt" onto your ribs. It floats on a bed of muscle. This is why your shoulder has such a crazy range of motion compared to your hip.

The humerus is your upper arm. Don't call it the "funny bone"—that’s actually the ulnar nerve running over the elbow. If you hit it, you aren't hurting the bone; you're shocking the nerve. Below that, you have the radius and the ulna. Here’s a trick: the radius is the one on the thumb side. It "radiates" around the ulna so you can turn your palm up and down.

- The femur is the heavyweight champion. It’s the longest and strongest bone in your body. It can support as much as 30 times your body weight.

- The tibia is your shin bone. It’s right under the skin, which is why getting kicked there hurts so bad.

- The fibula is the skinny one on the outside. You don't even really need it for weight-bearing; it's mostly there for muscle attachment.

The Problem with Traditional Labeling

When we look at labeled parts of a skeleton in a textbook, everything looks white and dry. In reality, your bones are pinkish. They are full of blood. Inside the long bones, like your femur, there is a factory called bone marrow. It’s pumping out millions of red blood cells every single second.

If you stop thinking of bones as "scaffolding" and start thinking of them as "mineral warehouses," you realize why things like osteoporosis are so scary. Your body needs calcium for your heart to beat. If you don't eat enough calcium, your body literally "robs the bank." It dissolves your skeleton to keep your heart ticking. Your ribs are basically a savings account for minerals.

The Pelvis: The Great Divider

Forensic anthropologists love the pelvis. Why? Because it’s the easiest way to tell if a skeleton was male or female. The female pelvis is wider and more circular. It has a larger "sub-pubic angle." Basically, it’s built to allow a human head to pass through it. The male pelvis is narrower and more heart-shaped.

When you see "pelvis" on a diagram, it’s actually three bones fused together: the ilium, ischium, and pubis. The ilium is the big "wing" you feel when you put your hands on your hips. The ischium is the "sit bone." If you're sitting on a hard wooden chair right now and your butt starts to hurt, blame your ischium.

📖 Related: Trump Says Don't Take Tylenol: Why This Medical Advice Is Stirring Controversy

Micro-Bones and Oddities

There is one bone in the human body that doesn't touch any other bone. It’s the hyoid. It’s U-shaped and sits in your throat, held in place by muscles. It’s the reason we can speak. If a forensic pathologist finds a broken hyoid during an autopsy, it’s a massive red flag—it usually indicates strangulation.

Then there are the sesamoid bones. These are tiny, pea-shaped bones embedded in tendons. Your patella (kneecap) is the biggest sesamoid bone in the body. It acts like a pulley, giving your thigh muscles more leverage to straighten your leg. Without that little bone, you’d need significantly more muscle mass just to walk up a flight of stairs.

Why Skeleton Models Often Fail Learners

The issue with standard labeled parts of a skeleton is that they ignore the "living" aspect. Bones are constantly being reshaped. This is called Wolff’s Law. If you lift heavy weights, your bones actually get denser and thicker. If you go to space, where there’s no gravity, your bones start to dissolve because the body thinks, "Well, I’m not using these, might as well recycle the calcium."

We also tend to overlook the joints. A skeleton is just a pile of sticks without the connective tissue. The cartilage on the ends of your bones is smoother than ice on ice. When that wears down, you get osteoarthritis. It’s basically bone grinding on bone, and it’s as painful as it sounds.

Anatomy Nuance: The Hands and Feet

Half of all your bones are in your hands and feet. Seriously.

- The carpals are the eight small bones in your wrist.

- The metacarpals make up your palm.

- The phalanges are your fingers (and toes).

The naming is almost identical for the feet, but we call the ankle bones tarsals. The calcaneus is your heel bone. It’s a massive hunk of bone designed to take the impact of your entire body weight every time your foot hits the ground. If you jump off a wall and land on your heels, that’s the bone that’s going to shatter.

👉 See also: Why a boil in groin area female issues are more than just a pimple

Misconceptions You Should Stop Believing

People often think bones are the hardest thing in the body. They aren't. Your tooth enamel is harder.

Another big one? That "bones are dead." If your bones were dead, a fracture would never heal. When you break a bone, the body sends in a "clean-up crew" of cells called osteoclasts to eat the debris. Then, osteoblasts come in and lay down new bone. It’s a literal construction site. Within a few months, the break is often stronger than the original bone around it.

Also, the "13th rib" thing. Most people have 12 pairs of ribs. But about 1% of the population is born with a "cervical rib" coming off their neck vertebrae. It can cause all sorts of nerve issues in the arm. It’s not a "missing link" or a religious sign—it’s just a common anatomical variation.

Actionable Steps for Learning Anatomy

If you actually want to memorize the labeled parts of a skeleton without losing your mind, don't just stare at a flat image.

- Use Palpation: Reach out and touch your own bones. Find your acromion process (the bony tip of your shoulder). Feel your malleolus (the bumps on your ankle). If you can feel it on yourself, you’ll remember the name.

- Group by Function: Don't just memorize names. Learn the "why." The thoracic vertebrae are built for stability to protect your lungs; the lumbar vertebrae are built for weight-bearing.

- Sketch It: You don't have to be an artist. Draw a stick figure and then try to "thicken" the bones. Label them as you go. The act of drawing creates a much stronger neural pathway than just reading.

- Study the Gaps: Look at the foramina—the holes in the bones. Every hole in a skeleton has a purpose. Usually, it's a "tunnel" for a nerve or a blood vessel. If you know what goes through the hole, you’ll understand why the bone is shaped that way.

The human skeleton isn't just a static frame. It’s a dynamic, reactive system that records the history of your life. Your bones show how you moved, what you ate, and even where you grew up. When you look at labeled parts of a skeleton, you're looking at the architectural blueprint of what it means to be a vertebrate. Treat it as a living map, and it starts to make a lot more sense.