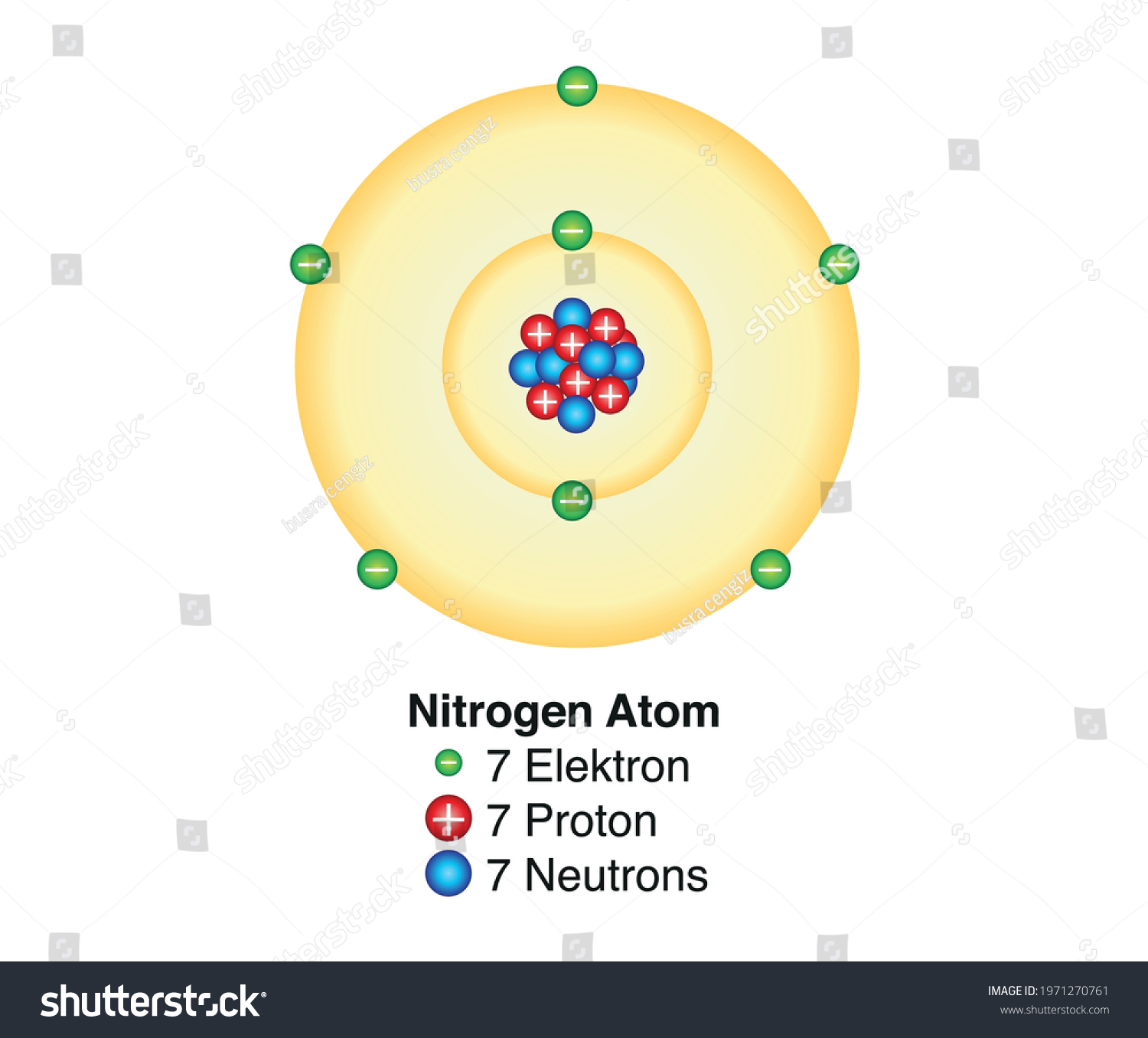

Everything is made of atoms. Your phone, the coffee you're sipping, the air you're breathing—it's all just a massive collection of these tiny, invisible building blocks. If you look at a labeled diagram of atom in a standard middle school textbook, you’ll see something that looks suspiciously like a solar system. There’s a clump in the middle and some little balls orbiting it like planets.

It’s simple. It’s clean. It’s also kinda wrong.

Don't get me wrong; that classic "Bohr model" is a great starting point for understanding how chemistry works. But if you really want to get into the weeds of how the universe is held together, we have to look past the pretty circles. Atoms are messy, vibrating clouds of energy and probability.

The Core Essentials: Protons, Neutrons, and the Nucleus

Let's start at the heart of the matter. The nucleus is the heavy hitter. It contains basically all the mass of the atom, yet it takes up an infinitesimally small amount of space. If an atom were expanded to the size of a football stadium, the nucleus would be about the size of a marble sitting on the 50-yard line.

Inside that marble, you've got two main players: protons and neutrons.

Protons are the identity of the element. They carry a positive charge. If you change the number of protons, you change the element entirely. One proton? You’ve got Hydrogen. Six? That’s Carbon. Seventy-nine? Now you're holding Gold. Scientists call this the Atomic Number. It's the DNA of the physical world.

Then there are neutrons. These guys are neutral—no charge. Their job is mostly to act as nuclear glue. Because protons are all positively charged, they naturally want to repel each other. Like trying to push two North poles of a magnet together. Neutrons provide the "Strong Nuclear Force" needed to keep the whole thing from flying apart.

When you see a labeled diagram of atom, the nucleus is usually shown as a cluster of red and blue spheres. In reality, these particles aren't just sitting there. They are constantly interacting through the exchange of even smaller particles called gluons. It's a high-stakes game of catch happening at the subatomic level.

👉 See also: Amazon Kindle Colorsoft: Why the First Color E-Reader From Amazon Is Actually Worth the Wait

The Electron Problem: Why Orbits are a Lie

This is where the standard labeled diagram of atom starts to fail us. We usually see electrons drawn as little dots on solid rings. This is the Bohr model, named after Niels Bohr. While it's great for calculating energy levels, it implies that electrons have a predictable path.

They don't.

Electrons are weird. They exist in what we call "orbitals" or "electron clouds." Instead of a track like a racecar, think of an electron as a swarm of bees or a hazy mist. You can't say exactly where an electron is at any given moment; you can only calculate the probability of where it might be.

The Quantum Mechanical Model

Modern science prefers the Quantum Mechanical Model. In this version of a labeled diagram of atom, the "rings" are replaced by shaded regions of various shapes—spheres, dumbbells, and even complex donut shapes.

- S Orbitals: These are spherical. The 1s orbital is the closest to the nucleus.

- P Orbitals: These look like two balloons tied at the ends.

- D and F Orbitals: These get incredibly complex and are where the heavy metals in the periodic table do their magic.

The electrons inhabit these spaces based on energy. Lower energy electrons stay close to the nucleus because they are attracted to the positive protons. Higher energy electrons—the "valence electrons"—hang out on the edges. These are the ones responsible for all chemical reactions. When two atoms "talk" to each other, they do it through their valence electrons. They swap them, share them, or steal them.

Mass vs. Volume: The Empty Space Paradox

Here is the part that usually blows people's minds. Atoms are mostly empty space. Like, 99.99999% empty.

If you removed all the "empty" space from the atoms that make up every human being on Earth, the entire human race would fit inside the volume of a sugar cube. However, that sugar cube would weigh five billion tons.

✨ Don't miss: Apple MagSafe Charger 2m: Is the Extra Length Actually Worth the Price?

So, why don't you fall through your chair if it's mostly empty space? It’s not because the atoms are "solid." It’s because of the electromagnetic repulsion of the electrons. When you sit down, the electrons in your pants are pushing against the electrons in the chair. You aren't actually "touching" the chair in a literal sense; you are hovering a microscopic distance above it, supported by the invisible force fields of trillions of atoms.

Beyond the Basics: Quarks and Subatomic Depth

If you really want to impress someone at a dinner party (or just ace a physics exam), you have to go deeper than protons and neutrons. For a long time, we thought those were the "fundamental" particles. We were wrong.

Protons and neutrons are actually made of even smaller things called Quarks.

- Up Quarks: Have a $+2/3$ charge.

- Down Quarks: Have a $-1/3$ charge.

A proton is made of two Up quarks and one Down quark. If you do the math ($2/3 + 2/3 - 1/3$), you get a total charge of $+1$.

A neutron is made of one Up quark and two Down quarks ($2/3 - 1/3 - 1/3$), which equals $0$.

There are other types of quarks too—Charm, Strange, Top, and Bottom—but they usually only show up in high-energy environments like the Large Hadron Collider or the moments immediately following the Big Bang.

Isotopes and Ions: Variations on a Theme

When looking at a labeled diagram of atom, it’s usually a "neutral" version of the element. But nature is rarely that perfect.

Isotopes occur when you have the right number of protons but a different number of neutrons. For example, Carbon-12 is the standard. It has 6 protons and 6 neutrons. But Carbon-14 has 6 protons and 8 neutrons. It’s still carbon, but it’s heavier and radioactive. This is exactly how archaeologists use carbon dating to figure out how old a mummy is.

🔗 Read more: Dyson V8 Absolute Explained: Why People Still Buy This "Old" Vacuum in 2026

Ions happen when an atom gains or loses electrons. If an atom loses an electron, it becomes a cation (positive). If it steals one, it becomes an anion (negative). This creates an electrical imbalance that makes atoms stick together like magnets, forming salts and minerals.

Why This Matters Today

Understanding the labeled diagram of atom isn't just an academic exercise. It's the foundation of almost all modern technology.

Semiconductors in your computer rely on our understanding of how electrons move through silicon lattices. MRI machines in hospitals work by manipulating the spin of protons in the hydrogen atoms of your body. Even the GPS on your phone relies on atomic clocks that measure the vibrations of cesium atoms to keep perfect time.

Without this "wrong" solar system model and the "right" quantum model, we’d still be in the dark ages of materials science.

Actionable Steps for Mastering Atomic Structure

If you're trying to memorize this for a test or just want to understand the universe better, don't just stare at a static image.

- Build a Mental Scale: Always remember the "stadium and the marble" analogy. It helps conceptualize why density matters.

- Focus on Valence: If you're studying chemistry, the inner electrons don't matter much. Focus your energy on the outermost shell. That's where the "action" is.

- Use Interactive Simulators: Tools like the PhET Interactive Simulations from the University of Colorado Boulder let you "build" an atom by dragging protons and electrons into place. It’s way more effective than a drawing.

- Learn the Trends: Instead of memorizing every atom, learn how the labeled diagram of atom changes as you move across the periodic table. Atoms generally get smaller as you move right (more protons pulling the electrons in tighter) and larger as you move down.

Understanding the atom is essentially understanding the source code of reality. It’s a bit weird, a lot empty, and infinitely complex.

---