Sound is invisible. That’s the first hurdle. When you’re looking at a labeled diagram of a sound wave, you aren't actually looking at "sound" itself, but rather a mathematical map of how air molecules are shoving each other around. It’s a representation. Most people see those curvy lines—the sine waves—and think air moves in big, rolling ocean waves. It doesn't. Air molecules wiggle back and forth in place.

If you want to truly understand how audio works, you have to get cozy with the anatomy of these diagrams. Whether you're a student trying to pass a physics quiz or a bedroom producer wondering why your bass sounds like a muddy mess, the labels on that graph matter. They are the DNA of every noise, from a whisper to a jet engine.

The Anatomy of a Wave: It’s All Pressure

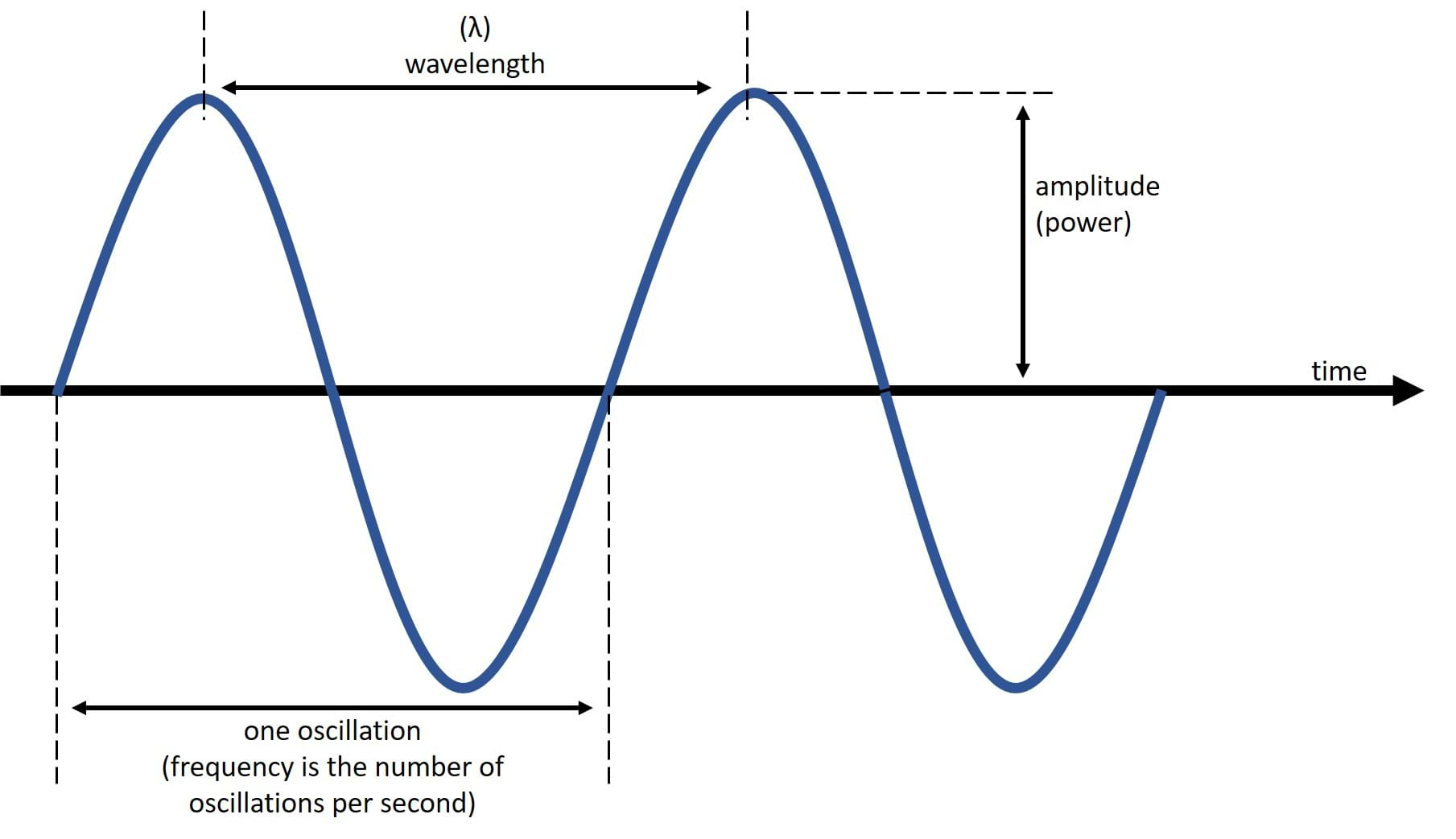

At its heart, a sound wave is a mechanical wave. It needs stuff to move through—air, water, or even solid steel. In a standard labeled diagram of a sound wave, you’ll usually see a horizontal line cutting through the middle. This is the "Equilibrium" or the "Rest Position." It represents the air pressure when everything is quiet.

When a sound happens, like a guitar string snapping, it pushes air molecules together. This creates a high-pressure zone called a Compression. On your diagram, this is the "peak" or the "crest." But for every push, there’s a pull. As the string moves back, it leaves a gap where air molecules are spread thin. This low-pressure zone is the Rarefaction, shown as the "trough" or the bottom curve of the wave.

Honestly, it’s kinda weird that we use curvy lines to describe something that is essentially a series of pulses. But it works because the height of that curve tells us exactly how much energy is in the wave.

Amplitude: The Volume Dial

Look at the distance between that center equilibrium line and the top of a crest. That’s your Amplitude. In the real world, this is what you perceive as volume or "loudness." The more energy you put into a sound—think screaming versus whispering—the higher those peaks get.

💡 You might also like: Premiere Pro Error Compiling Movie: Why It Happens and How to Actually Fix It

In digital audio workstations (DAWs) like Ableton or Logic, you see this constantly. If the amplitude gets too high and hits the top of the chart, the wave gets "clipped." The smooth curve turns into a flat line, and your ears get punished with a nasty, distorted crunch. Scientists measure this in decibels (dB), but on your diagram, it's just the vertical displacement. Higher peak? Louder noise. Simple.

Wavelength: The Physical Footprint

Now, look at the distance between two consecutive peaks. Or two troughs. It doesn't matter, as long as you're measuring from the exact same point on two back-to-back waves. This is the Wavelength, usually symbolized by the Greek letter lambda ($\lambda$).

Wavelength is fascinating because it’s a physical measurement of space. A low-frequency bass note at 20 Hz has a wavelength of about 17 meters. That’s huge. It’s longer than a semi-truck. This is why bass travels through walls so easily; the wave is literally too big for the wall to stop it. On the flip side, a high-pitched 20 kHz whistle has a wavelength of about 1.7 centimeters. Tiny.

Frequency and Period: The Time Factor

While amplitude is about "how high," frequency is about "how fast." If you’re looking at a labeled diagram of a sound wave, you might see a label for Period (T). This is the time it takes for one full cycle to complete.

- Frequency is the number of cycles that happen in one second, measured in Hertz (Hz).

- Pitch is how your brain interprets frequency. High frequency equals high pitch.

There is a hard-coded relationship here. If you shorten the wavelength, the frequency goes up. You can't change one without affecting the other. It’s physics. No way around it. When you hear a singer hit a "High C," their vocal folds are vibrating about 1,046 times per second. That means 1,046 little "crests" and "troughs" are hitting your eardrum every single second.

📖 Related: Amazon Kindle Colorsoft: Why the First Color E-Reader From Amazon Is Actually Worth the Wait

Why Phase Matters More Than You Think

Here is where things get messy. Phase is often a label on more advanced diagrams. It refers to where the wave is in its cycle at a specific point in time, measured in degrees ($0^\circ$ to $360^\circ$).

Imagine two identical sound waves. If they start at the exact same time, they are "in phase." They double in volume. But if one starts exactly half a cycle late ($180^\circ$ out of phase), the crest of one wave lines up perfectly with the trough of the other. They cancel each other out. Total silence. This is exactly how noise-canceling headphones work. They "read" the noise around you and instantly generate an inverted sound wave to kill the sound before it reaches your brain. It's basically magic, but it’s really just basic wave geometry.

Real-World Nuance: Longitudinal vs. Transverse

Most labeled diagrams of a sound wave show a transverse wave—that classic "S" shape. But sound is actually a longitudinal wave.

In a transverse wave (like a wave on a string), the medium moves up and down while the energy moves forward. In a longitudinal wave (sound), the particles move back and forth in the same direction the energy is traveling.

We only draw them as transverse waves because it's way easier to label a peak and a trough than it is to draw a bunch of tiny dots representing air molecules. If you see a diagram with "zones of compression" and "zones of rarefaction" labeled with clusters of dots, you're looking at a more "honest" representation of how sound actually moves through a room.

👉 See also: Apple MagSafe Charger 2m: Is the Extra Length Actually Worth the Price?

Beyond the Basics: Harmonics and Timbre

Why does a trumpet sound different than a piano even if they play the same note? If you looked at a perfectly clean labeled diagram of a sound wave for a tuning fork, it would be a smooth, boring sine wave. This is a "pure tone."

But real instruments don't produce pure tones. They produce a fundamental frequency (the main note) plus a bunch of smaller, faster waves called Overtones or Harmonics.

When you label a complex sound wave, the "jaggedness" of the line represents its Timbre. A violin wave looks like a saw blade—lots of sharp corners and extra little peaks. A flute wave looks much smoother, closer to that perfect sine wave. These extra labels for harmonics explain why a $10,000 guitar sounds "richer" than a $50 one; it’s literally producing more complex geometry in the air.

Actionable Steps for Using This Knowledge

Understanding a labeled diagram of a sound wave isn't just for passing tests. It has practical applications if you deal with audio in any capacity.

- Check your Phase: If you’re recording a podcast with two mics and the voices sound "thin" or "hollow," your waves might be partially out of phase. Try moving one mic a few inches. This changes the wavelength distance to the source and can "re-align" the peaks.

- Manage your Amplitude: When recording digital audio, keep your peaks around -12dB to -6dB. This gives you "headroom." If your amplitude hits the 0dB ceiling on your diagram, the information is lost forever to clipping.

- Acoustic Treatment: Remember that low-frequency waves have long wavelengths. If you have "boomy" bass in your room, a thin foam panel won't help. The wave is literally bigger than the foam. You need thick "bass traps" to catch those 17-meter-long waves.

- Visualize the Frequency: Use a software tool called a Spectrogram. It’s basically a 3D labeled diagram of a sound wave that shows frequency over time. It’s the best way to "see" noise and find exactly where a problematic sound is hiding.

The diagram is the map, but the sound is the journey. Once you can read the map, you stop guessing and start knowing exactly why things sound the way they do. High peaks, tight wavelengths, and clean phases—that’s the secret to great audio.