You probably think you know your body. Most people do. But then you sit down to label the skeleton bones for a biology quiz or a physical therapy cert, and suddenly, the "thigh bone" isn't just the femur—it’s a complex landscape of trochanters and condyles that look nothing like the plastic model in your high school classroom.

The human skeleton is weird. It’s a 206-piece jigsaw puzzle made of living tissue that constantly regenerates. Honestly, most "complete" charts you find online are kinda misleading because they simplify things to the point of being useless for actual medical understanding. If you’re trying to master this, you have to stop looking at the skeleton as a static object. It's a dynamic system.

Did you know that you were born with about 270 bones? By the time you’re reading this, dozens of them have fused together. Your sacrum, that shield-shaped bone at the base of your spine, started as five separate vertebrae. If you’re a teenager, your long bones still have "growth plates" made of cartilage that haven't even hardened into bone yet.

Why Modern Labels Often Fail Beginners

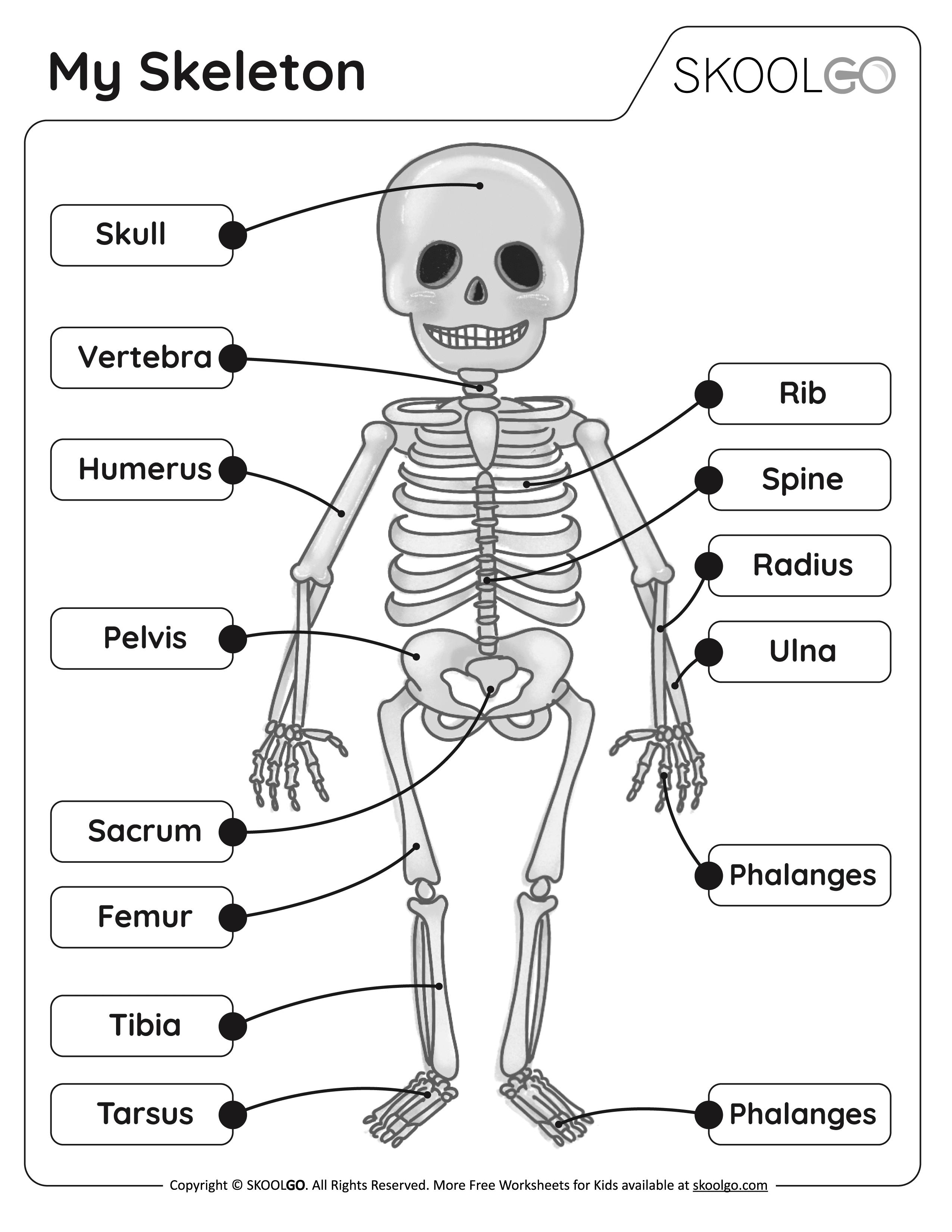

When you start to label the skeleton bones, the first mistake is treating every bone as equally important. It’s not a flat list. You've got the axial skeleton—the core 80 bones like the skull and spine—and the appendicular skeleton, which covers the 126 bones in your limbs and girdles.

Most people trip up on the hands and feet. It’s understandable. There are 27 bones in a single human hand. That means over 10% of your entire bone count is located just between your wrist and your fingernails. If you can’t tell your scaphoid from your lunate, don’t beat yourself up. Even med students at Johns Hopkins have to use mnemonics like "Some Lovers Try Positions That They Can't Handle" just to remember the carpal rows.

The Skull Is Not One Piece

Think the "cranium" is just one big helmet? Not even close. It's a collection of 22 bones joined by "sutures," which are basically fixed joints that look like jagged cracks.

- The Frontal Bone: Your forehead. Simple enough.

- The Parietal Bones: Two plates forming the bulk of the roof and sides.

- The Sphenoid: This is the cool one. It’s shaped like a butterfly and sits right in the middle of the skull, wedged between everything else.

If you're trying to label the skeleton bones for a test, the sphenoid is the one that proves you actually know your stuff. It touches almost every other cranial bone. It’s the keystone. Without it, your face would basically lose its structural integrity.

The Trickiest Parts of the Axial Skeleton

The spine is where things get messy. You have 7 cervical (neck), 12 thoracic (mid-back), and 5 lumbar (lower back) vertebrae. A quick way to remember that? Think of meal times: breakfast at 7, lunch at 12, dinner at 5.

But here’s what experts look for: the Atlas and the Axis. These are the C1 and C2 vertebrae. The Atlas holds up your head (like the Greek Titan), and the Axis allows it to rotate. If you’re labeling a diagram and you mix these two up, the whole neck structure ceases to make sense.

The Rib Cage Nuance

It’s not just "ribs." You have "true ribs," "false ribs," and "floating ribs."

The first seven pairs attach directly to the sternum. The next three attach to the cartilage of the rib above them. The last two? They just hang there. They don't attach to the front at all. This is why a hard hit to the lower back is so dangerous—those floating ribs don't have the structural support of the sternum to help absorb the impact.

Moving Into the Appendicular: The Limbs

The femur is the heavy hitter. It's the longest and strongest bone in your body. It can support up to 30 times your body weight. That’s incredible. But when people label the skeleton bones in the leg, they often forget the patella (kneecap).

🔗 Read more: Loden Vision Goodlettsville TN: What Most People Get Wrong About Modern Eye Care

The patella is a "sesamoid" bone. It’s actually embedded inside a tendon. It acts like a pulley, giving your quadriceps more leverage so you can kick or jump with more force. Without that tiny bone, your legs would be significantly weaker.

The Confusion of the Forearm

The radius and the ulna. Which is which?

The radius is on the thumb side. Think of a "radial" tire or a "radius" of a circle—it rotates around the ulna. When you turn your palm down, the radius literally crosses over the ulna. If you’re looking at an anatomical diagram where the palms are facing forward (anatomical position), they are parallel. If the palms are facing the body, they’re crossed. This is a classic "gotcha" on anatomy exams.

Complexities Most Charts Ignore

We need to talk about the hyoid. It’s a tiny, U-shaped bone in the throat. What makes it unique? It is the only bone in the entire human body that doesn't touch another bone. It’s held in place entirely by muscles and ligaments. It’s the "lonely bone."

Then there are the ossicles. Deep inside your middle ear are the malleus, incus, and stapes. The stapes is the smallest bone in your body—it’s roughly 3 millimeters by 2.5 millimeters. You could fit a handful of them on a single penny. When you label the skeleton bones, these are often omitted because they're so small, but without them, you’d be completely deaf. They vibrate to translate sound waves into something your brain can understand.

💡 You might also like: The Svelte 7 Minute Workout: Why High-Intensity Science Still Beats Long Gym Sessions

The Pelvis Difference

If you are looking at a skeleton and trying to determine if it’s male or female, the pelvis is the smoking gun. A female pelvis is wider and shallower, with a broader pubic arch (usually greater than 90 degrees) to allow for childbirth. A male pelvis is narrower, heavier, and has a much tighter arch. Forensic anthropologists like Dr. William Bass, who founded the "Body Farm" at the University of Tennessee, rely on these specific markers to identify remains.

Real-World Application: Why This Matters

Learning to label the skeleton bones isn't just about passing a test. It’s about understanding injury.

- Colles' Fracture: This is a break in the distal radius. It happens when you trip and try to catch yourself with an outstretched hand. If you know where the radius is, you understand why your wrist looks like an upside-down fork after a fall.

- Shin Splints: This isn't usually a bone break, but it involves the periosteum (the "skin" of the bone) being pulled away from the tibia.

- Ankle Sprains: Most people think they "broke their ankle," but they often just tore ligaments connecting the fibula to the talus.

Knowing the names gives you a map. Without the map, you’re just guessing where the pain is coming from.

Best Practices for Memorization

Don't just stare at a printed sheet. It doesn't work. Your brain is built to recognize 3D shapes, not 2D ink.

- Use your own body. Touch your "olecranon" (the pointy part of your elbow). Feel the "malleolus" (the bumps on your ankle). Associating a name with a physical sensation locks the memory in way faster.

- Draw it poorly. You don't need to be Da Vinci. Sketch the humerus. Make it look like a dog bone if you have to. The act of drawing forces your brain to process the proportions.

- Group by region. Don't try to learn all 206 at once. Spend Monday on the skull. Tuesday on the torso. Wednesday on the arms.

- Flashcards with a twist. Put the name on one side and a "real-world" fact on the other. Instead of just "Femur," write "Femur - Stronger than concrete."

The "Floating" Problem

A lot of beginners forget the scapula (shoulder blade) isn't bolted to the ribs. It's held there by muscles. This is why your shoulders have such a massive range of motion compared to your hips. The hip joint (where the femur meets the pelvis) is a deep "ball and socket" designed for stability. The shoulder is a shallow "ball and socket" designed for mobility.

When you label the skeleton bones, pay attention to the joints. The points where the bones meet tell the story of how that part of the body is supposed to move.

Action Steps for Mastering the Skeleton

If you really want to nail this, stop using generic Google Image search results. They are often cluttered with ads or oversimplified.

- Download a 3D Anatomy App: Apps like Complete Anatomy or Essential Anatomy let you rotate the bones. Seeing the posterior (back) side of a bone is often the "aha" moment.

- Get a physical model: You can buy a miniature desktop skeleton for twenty bucks. Being able to physically point to the sternum or the ilium makes the names stick.

- Focus on the "Bumpy Parts": In higher-level anatomy, you don't just label the bone; you label the "landmarks." Learn where the "greater tubercle" is on the humerus. It sounds overkill, but it makes the bone names feel like second nature.

- Test yourself backwards: Look at a bone and try to name three muscles that attach to it. If you know the bicep attaches to the radial tuberosity, you’ll never forget where the radius is.

The human frame is an engineering marvel. It's light enough to let us run marathons but strong enough to protect our most vital organs. Once you start to label the skeleton bones with a bit of curiosity instead of just rote memorization, you’ll realize you aren't just looking at a pile of calcium—you're looking at the ultimate architectural blueprint.