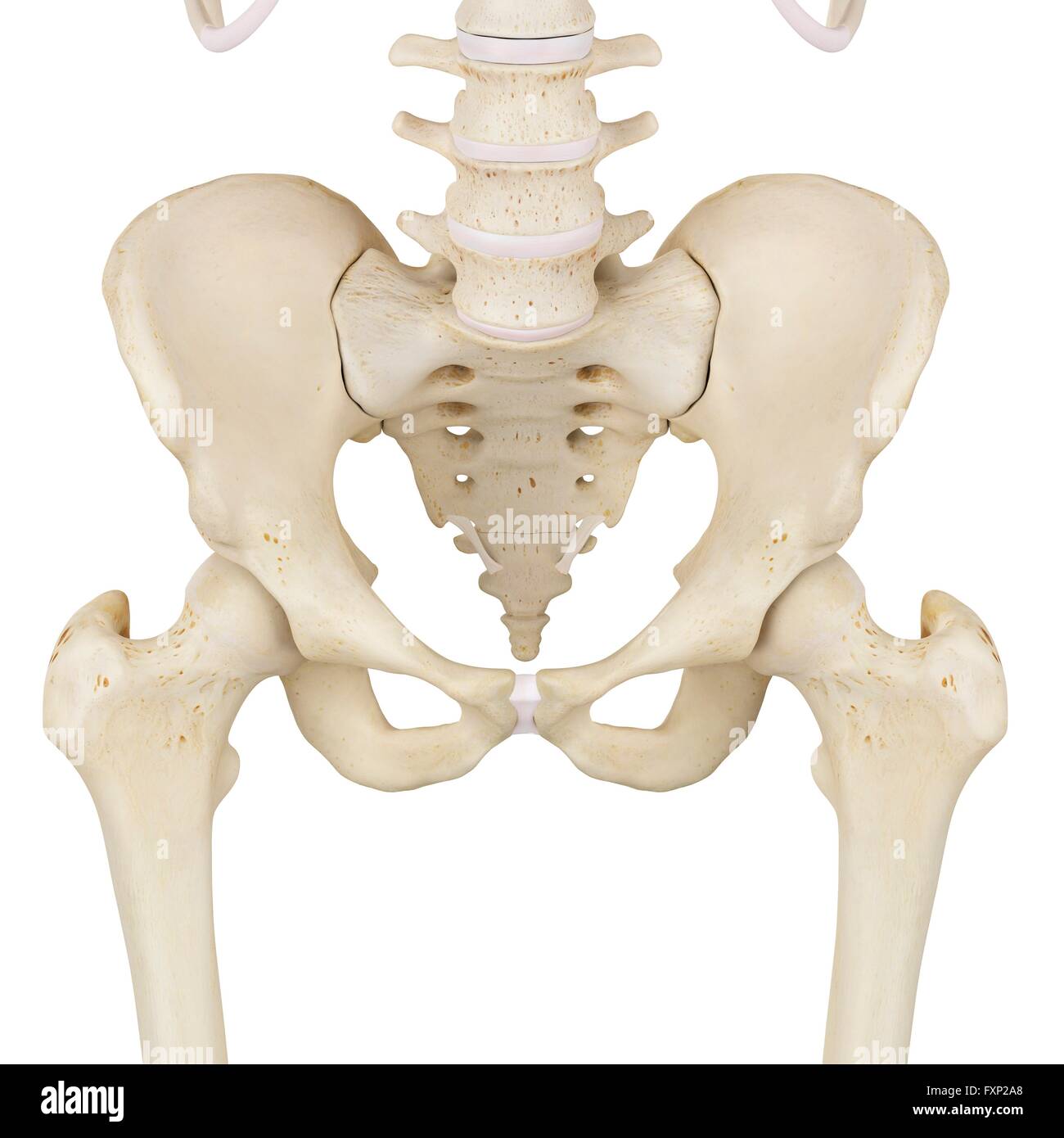

If you’ve ever tried to label bones of pelvis for a pre-med exam or just because your lower back feels like a bag of gravel, you probably realized pretty quickly that "the hip bone" is a total lie. It’s not one bone. It’s a chaotic, fused-together mess of three different bones that decided to join a club during your teenage years.

Honestly, the pelvis is the ultimate architectural compromise. It has to be stable enough to support your entire upper body weight, but flexible enough to let you walk, run, and—for about half the population—squeeze a human being out of it. Most diagrams make it look like a simple butterfly shape. In reality, it’s a bowl-shaped complex of rigid struts and shock absorbers.

The Ilio-C-S Triple Threat

When people sit down to label bones of pelvis, they usually start with the big, flared wings. That’s the Ilium. If you put your hands on your hips, that hard ridge you’re feeling is the iliac crest. It’s the "handle" of your pelvis. But go deeper.

🔗 Read more: Pictures of Moles That Are Not Cancerous: What Your Skin Is Actually Trying to Tell You

Underneath that, tucked toward the back and bottom, you’ve got the Ischium. This is literally your "sitting bone." If you’re sitting on a hard wooden chair right now and feel two bony points poking into the seat, congratulations, you’ve found your ischial tuberosities. Then there’s the Pubis, located at the front. These three—the ilium, ischium, and pubis—start as separate pieces of cartilage in a baby. They don't fully ossify and fuse into a single "innominate bone" (also called the os coxae) until you’re somewhere between 15 and 25 years old.

Why does this matter? Because many "hip" injuries aren't in the hip joint at all. They’re often stress fractures or ligament pulls at the junctions where these bones meet.

The Mystery of the Sacrum and Coccyx

You can’t talk about the pelvic girdle without the spine's basement. The Sacrum is that large, triangular bone wedged right between your two hip bones. It’s basically a massive keystone in an arch. Without it, your pelvis would just collapse inward. It’s actually five fused vertebrae.

Then we get to the Coccyx. Your tailbone.

It’s tiny. It’s fragile. And if you’ve ever slipped on ice and landed on it, you know it’s the most disproportionately painful bone in the body. It doesn't really "do" much for structural support, but it serves as an attachment point for various muscles and ligaments of the pelvic floor. When you label bones of pelvis structures, don't ignore the Coccyx just because it’s small. It’s the vestigial remnant of our ancestors' tails, and it still carries a lot of tension.

Breaking Down the Landmarks

Let's get specific. If you're looking at a medical diagram, you aren't just looking for the bones; you're looking for the holes and the bumps.

📖 Related: Why causes of water retention are making you feel bloated—and what's actually going on

- The Acetabulum: This is the deep, vinegar-cup-shaped socket where the head of your femur (thigh bone) sits. It’s actually the meeting point of all three pelvic bones.

- The Obturator Foramen: These are the two giant holes at the bottom. They look like eyes staring at you. They aren't just for weight reduction; they allow nerves and blood vessels to pass through to your legs.

- The Greater Sciatic Notch: A massive curve in the ilium where the sciatic nerve—the thickest nerve in your body—travels down into your leg.

Why Men and Women Can't Use the Same Labeling Map

Sexual dimorphism in the pelvis is one of the coolest things in forensic osteology. If a scientist finds a skeleton, the pelvis is the first thing they check to determine sex.

Men usually have a "heart-shaped" pelvic inlet. It’s narrow and heavy, built for pure load-bearing and bipedal efficiency. Women have a much wider, circular "basin-shaped" pelvis. The pubic arch (the angle where the two pubic bones meet at the front) is usually wider than 90 degrees in females, while it’s much sharper—usually less than 70 degrees—in males.

Evolution basically played a game of "how wide can we make this before the person can't walk?" The result is the "obstetrical dilemma." A woman's pelvis is a masterpiece of compromise between the mechanical requirements of upright walking and the space requirements for childbirth.

What Most People Get Wrong About Pelvic Alignment

We talk a lot about "pelvic tilt." You’ve probably heard a gym coach tell you to fix your "anterior pelvic tilt."

Basically, this happens when the front of your ilium drops forward and the back rises. It creates a massive arch in your lower back. People think this is a bone problem. It’s usually a muscle problem. Your hip flexors are too tight, and your glutes are too weak. The bones are just the passengers here.

When you label bones of pelvis in your mind, try to visualize them not as static rocks, but as a dynamic suspension system. The sacroiliac (SI) joint, where the sacrum meets the ilium, only moves about 2 to 4 millimeters. That’s almost nothing. But if those 2 millimeters get stuck or move too much? You’re in for a world of hurt.

The Role of the Pelvic Floor

You can't have the bones without the "hammock." The pelvic floor muscles attach directly to the interior surfaces of the pubis and the coccyx. They hold your organs in place. If the bones of the pelvis aren't aligned—say, due to a fracture or a severe ligamentous laxity—the muscles have to work overtime to keep your bladder and intestines from sagging.

Think of the pelvic bones as the frame of a house. If the frame is crooked, the dry-wall (the muscles) is going to crack.

Clinical Significance of Pelvic Fractures

Pelvic fractures are terrifying. Because the pelvis is a ring, it’s almost impossible to break it in just one place. Think of a pretzel. If you try to snap a pretzel ring, it almost always breaks in two spots.

High-impact trauma, like a car accident, can cause a "vertical shear" fracture or an "open book" fracture. In an open book fracture, the pubic symphysis (the cartilage joint at the very front) actually rips apart. Because there are so many major arteries—like the internal iliac artery—running right along these bones, a pelvic break is often a life-threatening medical emergency due to internal bleeding.

Actionable Steps for Pelvic Health

Knowing how to label bones of pelvis is step one. Protecting them is step two.

- Check your seat. If you sit for 8 hours a day, you are putting constant pressure on the ischial tuberosities and the coccyx. Use a cushion that has a cutout for the tailbone if you have lingering pain.

- Strengthen the "Side Glutes." The Gluteus Medius attaches to the outer wing of the ilium. If this muscle is weak, your pelvis will drop every time you take a step, leading to hip and knee pain. Side-lying leg raises or "clamshells" are your best friend.

- Pelvic Tilts for Mobility. Lie on your back and gently arch your lower back off the floor, then flatten it down. This keeps the sacroiliac joints from getting "stuck."

- Bone Density Matters. The pelvis is a common site for osteoporotic fractures in older age. Weight-bearing exercise—literally just walking or lifting light weights—signals the ilium and sacrum to stay dense and strong.

The pelvis isn't just a static bucket for your guts. It's a complex, fused architectural marvel that bridges the gap between your spine and your legs. Understanding the specific landmarks—from the flared iliac wings to the tiny coccyx—is the only way to truly understand how your body moves and where your pain might actually be coming from. Stop thinking of it as one bone. Start seeing the three-part harmony of the ilium, ischium, and pubis.

✨ Don't miss: Why Cabrini Medical Center New York Still Matters Long After Closing Its Doors

Next Steps for Deep Learning:

Audit your posture by standing in front of a mirror and placing your fingers on your Anterior Superior Iliac Spines (ASIS)—the bony points at the front of your hips. If one hand is significantly higher than the other, or if they are pointing toward the floor rather than straight ahead, your pelvic alignment is likely affecting your gait and spinal health. Consult a physical therapist to see if your "bone pain" is actually a muscular imbalance pulling these structures out of their neutral "bowl" position.