Ever sat in a physics lab, staring at a squiggly line on a page, and felt like you were looking at a heartbeat monitor? That's the vibe. When you're asked to label a transverse wave, it seems like a middle school memory test, but honestly, there's a lot more going on under the hood than just memorizing "crest" and "trough."

Waves are everywhere. Light. Radio. Slinkies. Even the "wave" at a stadium.

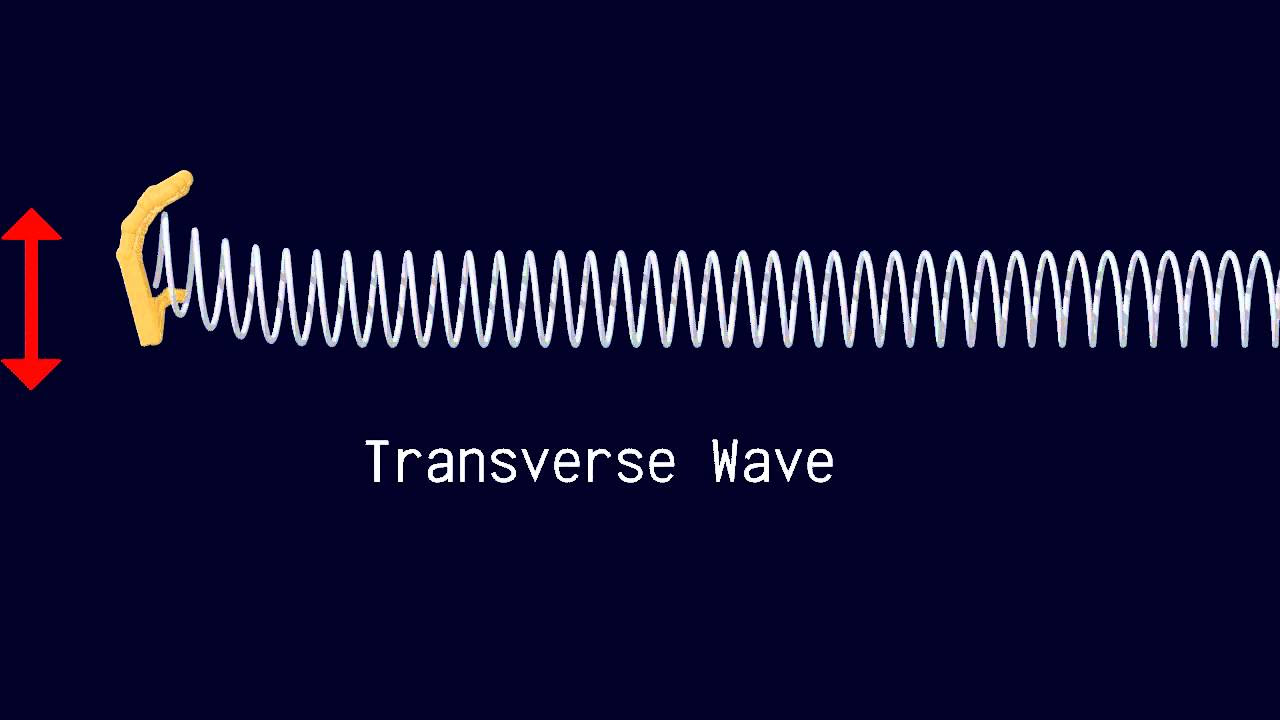

But here is the thing: most people mess up the labels because they don't actually understand the motion. A transverse wave isn't just a shape; it's a specific relationship between where the energy is going and where the particles are moving. If you get that wrong, the labels are just words.

Why the Labels Matter More Than You Think

When we talk about light or electromagnetic radiation, we're talking about transverse waves. If you can't accurately label a transverse wave, you're going to struggle with everything from fiber optics to how your microwave doesn't kill you. It's the foundation of modern communication.

Think about a rope tied to a door handle. You shake it up and down. The "energy" or the wave itself travels toward the door. But the actual rope? It’s just moving up and down. It's not going anywhere. That perpendicular relationship—90 degrees, a right angle, call it what you want—is the definition of "transverse."

The Core Anatomy You Have to Know

If you’re looking at a diagram right now, you’re probably seeing a horizontal line cutting through the middle of the wave. That’s the rest position. Or the equilibrium. Basically, it’s where the rope would be if you stopped shaking it like a maniac.

- The Crest: This is the peak. The highest point. It’s the maximum positive displacement from that middle line.

- The Trough: The valley. The lowest point. It’s the maximum negative displacement.

Pretty simple, right? But here is where it gets tricky for people.

Amplitude is the distance from the rest position to the crest. Or the rest position to the trough. It is NOT the distance from the top to the bottom. I see students and even some tech writers make this mistake constantly. If you measure from the very top to the very bottom, you’ve just doubled your amplitude, and in the world of physics, that’s the difference between a whisper and a scream, or a dim light and a blinding flash.

Wavelength and the Math of Space

Now, let's talk about Wavelength. Usually, we use the Greek letter lambda ($\lambda$) for this.

You can measure it from one crest to the next crest. Easy. Or from one trough to the next. Also easy. But you can actually measure it from any point on the wave to the next identical point where the wave starts repeating itself.

🔗 Read more: TikTok Profile Pic: What You're Probably Getting Wrong About Your Brand

Imagine you're walking along the wave. The moment you feel like you're experiencing "deja vu"—that's one wavelength.

Why does this matter? Well, consider the visible spectrum. Red light has a longer wavelength (around 700 nanometers) than violet light (around 400 nanometers). When you label a transverse wave in a lab setting, you’re basically defining the "color" or "identity" of that wave.

The Time Factor: Frequency and Period

You can’t really label a static drawing with frequency, but you have to understand it to know what the drawing represents. Frequency is how many of those wavelengths pass a point in one second. Measured in Hertz (Hz).

If you have a high frequency, your drawing is going to look like a bunch of tight, frantic zig-zags. Low frequency? Long, lazy rolls.

There's a fundamental equation here that every engineer lives by:

$$v = f \lambda$$

Velocity equals frequency times wavelength. In a vacuum, light always travels at the same speed ($c$). So, if the frequency goes up, the wavelength must go down. They are inversely proportional. It’s a cosmic see-saw.

Common Misconceptions When Labeling

I've seen some weird stuff in textbooks over the years. One major point of confusion is the difference between a transverse wave and a longitudinal wave.

In a longitudinal wave (like sound), the particles move back and forth in the same direction the wave travels. Think of a spring being pulsed. There are no "crests" or "troughs" in the traditional sense; there are compressions and rarefactions.

Don't try to use transverse labels on a sound wave diagram unless you're looking at a transformed "pressure vs. time" graph. That’s a trap. A pressure-time graph looks like a transverse wave, but it’s actually a representation of longitudinal data.

💡 You might also like: Control Panel Inside Out: Why This Retro Tech Still Runs Your World

Real-World Nuance: Polarization

One thing you won’t usually see on a basic "label the wave" worksheet is polarization. Since transverse waves move up and down (or side to side), they have an orientation.

Imagine trying to push a flat piece of wood through a picket fence. If the wood is vertical, it slides through the gaps. If it's horizontal, it hits the slats.

Light does this too. Sunglasses use "polarizing" filters to block certain orientations of transverse light waves, which is how they cut down on glare from the sun hitting a flat road or water. If light were a longitudinal wave, those sunglasses wouldn't work at all.

How to Actually Draw This for a Report

If you’re tasked to label a transverse wave for a project or a professional technical document, don't just draw a squiggle.

- Step 1: Draw a straight, dashed horizontal line first. This is your zero-point. Label it Equilibrium.

- Step 2: Draw your sine wave. Make it symmetrical. If your crests are taller than your troughs are deep, your math is going to be wrong later.

- Step 3: Use a double-headed arrow to show Wavelength. Draw it between two identical points.

- Step 4: Use a single-headed arrow from the equilibrium line to a crest to show Amplitude.

- Step 5: Point to the highest and lowest points for Crest and Trough.

It’s about clarity.

The Energy Connection

The most important thing to remember—and this is what separates the experts from the students—is that the amplitude is tied to the energy.

In a mechanical wave, the energy is proportional to the square of the amplitude.

$$E \propto A^2$$

If you double the height of that wave you're labeling, you haven't just doubled the energy; you've quadrupled it. This is why tsunamis (which aren't purely transverse but have transverse components in deep water) are so devastating. A small increase in "height" or displacement results in a massive jump in the power the wave carries.

Deep Dive: Electromagnetic Waves

When we label a transverse wave in the context of electromagnetism, we're actually looking at two waves at once.

An electromagnetic wave consists of an electric field and a magnetic field. They are both transverse. And they are perpendicular to each other.

So, if the electric field is waving up and down (vertical), the magnetic field is waving left and right (horizontal). Both are perpendicular to the direction of travel. It’s a 3D dance of energy. When you see a simplified 2D drawing in a textbook, keep in mind it's a "slice" of what’s actually happening.

Why Does This Matter for Technology?

Your phone. Your Wi-Fi. Your GPS.

All of these rely on the precise manipulation of these wave characteristics. When a service provider talks about "frequency bands," they are talking about how many of those crests hit your antenna per second. When a signal is "weak," it often means the amplitude has dropped because the wave lost energy traveling through walls or trees.

If you can't accurately identify these parts on a spectrum analyzer, you can't troubleshoot a network.

Summary of Actionable Insights

You've got the basics down, but applying them is where the value is. Whether you're a student, a hobbist, or someone getting into RF (Radio Frequency) engineering, here is how you use this:

📖 Related: Costco AirPods Pro 2: What Most People Get Wrong About the Deal

- Check your reference point: Always measure amplitude from the center, never top-to-bottom.

- Identify the medium: Remember that transverse waves need a medium (like a string) or can travel through a vacuum (like light). Sound is never transverse in air.

- Watch the units: Wavelength is distance (meters, nanometers). Frequency is time-inverse (Hertz). Don't swap them.

- Visualize the 90-degree rule: If you're ever unsure if a wave is transverse, ask: "Is the stuff moving sideways while the wave moves forward?" If yes, it's transverse.

Next time you see a diagram to label a transverse wave, you won't just be filling in boxes. You'll be looking at the fundamental way energy moves through the universe.

To take this further, try using a physics simulator like PhET to see how changing the frequency in real-time affects the wavelength. Or, grab a heavy rope, tie it to something solid, and try to create a "standing wave" where the nodes stay still. Seeing the physical displacement of the rope makes the concept of amplitude much more "real" than a drawing on a screen ever will.

Pay close attention to the "nodes"—the points where the wave crosses the equilibrium. In a standing wave, these points don't move at all. It’s a weird, beautiful quirk of physics that happens when two transverse waves interfere with each other perfectly. Understanding those points is the key to musical instruments like guitars and violins. One label leads to another, and before you know it, you're looking at the math of music.

Keep your labels precise. Keep your measurements from the equilibrium. And always remember that the wave is a graph of energy in motion, not just a static shape on a page.

Next Steps for Mastery:

- Practice Measurement: Download a waveform generator app on your phone. Use the "pause" function to take a screenshot and manually calculate the wavelength based on the time-stamp on the x-axis.

- Compare Mediums: Research why transverse waves cannot travel through liquids or gases (hint: it's about shear strength). This explains why S-waves from earthquakes don't pass through the Earth's liquid outer core.

- Explore Phase: Once you're comfortable with the labels, look into "phase shift." This is when two waves are identical but one is "offset" from the other, a concept vital for noise-canceling headphones.

Ultimately, the ability to label a transverse wave is the first step into a much larger world of wave mechanics that governs almost everything we see and hear.