It starts with a woman in a beige bodysuit. She looks like a mannequin, or maybe a canvas. Honestly, if you haven't seen la piel que habito pelicula in a few years, the first thing that hits you upon rewatching is how clinical it feels compared to Pedro Almodóvar’s usual explosion of primary colors and kitsch. It’s cold. It’s surgical. It’s a movie that lives under your fingernails long after the credits roll.

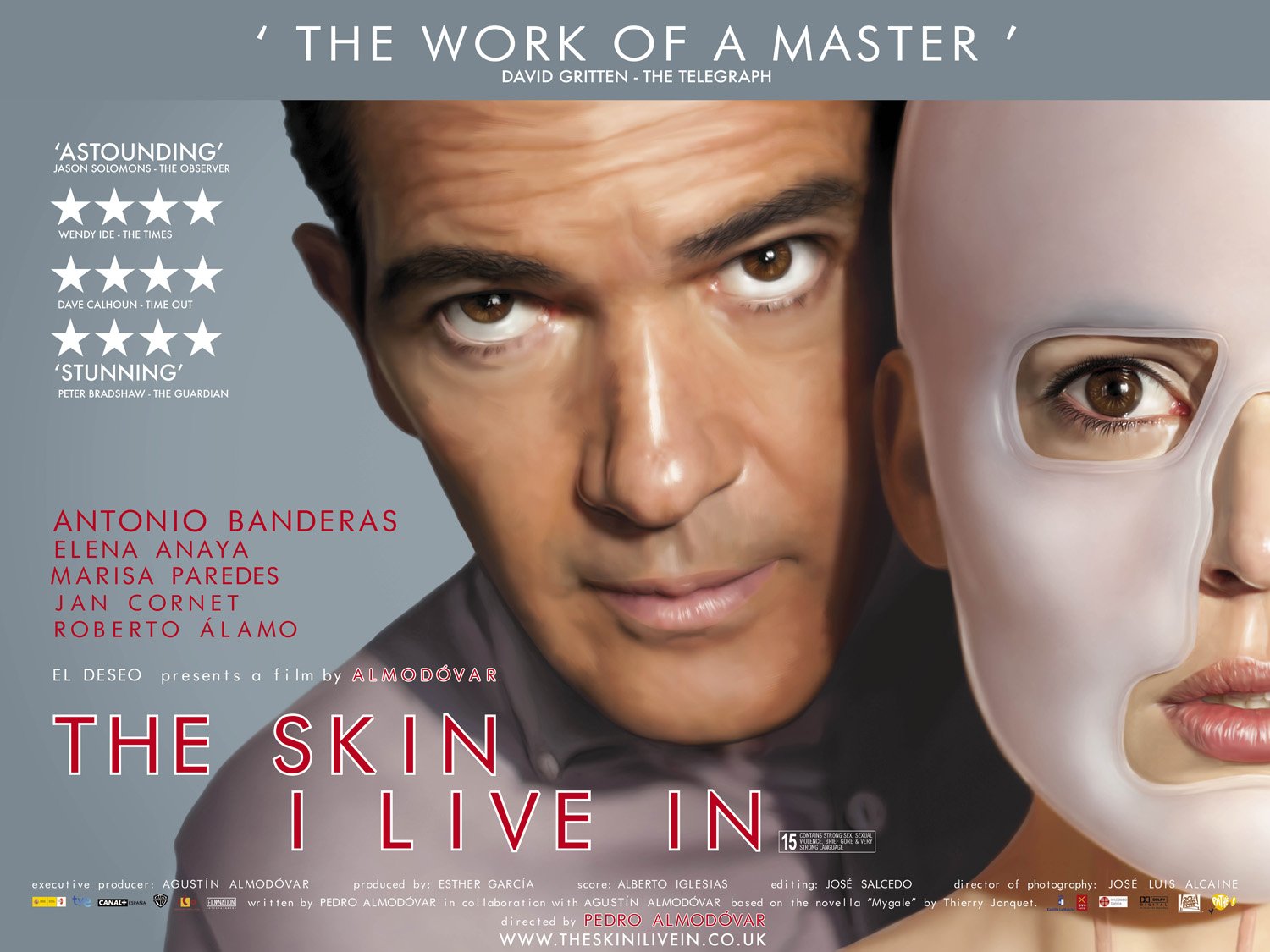

Released in 2011, this wasn't just another entry in the Spanish director's filmography. It was a pivot. Based loosely on Thierry Jonquet’s novel Tarantula, the film reunited Almodóvar with Antonio Banderas after decades apart. Banderas plays Dr. Robert Ledgard, a brilliant plastic surgeon who is—to put it lightly—completely unhinged by grief and obsession. He’s trying to create a synthetic skin that can withstand burns, inspired by the tragic death of his wife. But the "how" and the "who" of his experiment is where the movie turns into a psychological nightmare.

The Horror of Identity in La piel que habito pelicula

Most people categorize this as a thriller. Some call it "body horror." I think it’s more of a twisted Greek tragedy dressed up in high-fashion medical scrubs. The core of la piel que habito pelicula isn't the gore—there's actually surprisingly little of it—but the violation of the self.

Think about the concept of "the skin." It’s our boundary. It’s where we end and the world begins. Ledgard isn't just trying to heal people; he's trying to play God by rewriting the physical identity of another human being. The character of Vera, played with a haunting, glassy-eyed intensity by Elena Anaya, becomes the literal vessel for his madness.

The plot twist—and if you haven't seen it, maybe skip this paragraph, though it's been over a decade—is one of the most audacious in modern cinema. It recontextualizes every touch and every look from the first hour. It turns a story about "creation" into a story about "erasure." When we talk about Almodóvar, we usually talk about mothers, sisters, and the strength of women. Here, he explores the terrifying power of a man trying to force a woman into existence from the wreckage of his own past.

A Masterclass in Visual Subversion

Jean Paul Gaultier designed the costumes. Let that sink in. The "skin" Vera wears is a Gaultier creation, meant to look like a second epidermis. It’s sleek, restrictive, and deeply unsettling.

💡 You might also like: Not the Nine O'Clock News: Why the Satirical Giant Still Matters

Almodóvar uses the architecture of Ledgard’s estate, El Cigarral, to reinforce the themes of imprisonment. Everything is limestone, glass, and expensive art. It’s beautiful, but it’s a tomb. The cinematography by José Luis Alcaine opts for sharp lines and deep shadows. It’s a far cry from the chaotic, cluttered apartments of Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown.

- The Artistry: Look at the walls. Ledgard is surrounded by massive paintings, including works by Titian. These aren't just background decorations; they represent the classical obsession with the female form as an object to be captured and preserved.

- The Silence: Alberto Iglesias’s score is anxious. It uses strings that feel like they're being pulled too tight.

- The Contrast: While the surgery is high-tech, the emotions are primal. It’s revenge. It’s lust. It’s pure, unadulterated ego.

The film operates on a weird frequency. It’s almost a soap opera in its plot beats—secret brothers, tragic accidents, hidden identities—but the execution is so disciplined that it never feels campy. It feels dangerous.

Why the Science (Sort of) Matters

While the film is a fantasy, it touched on real-world bioethical concerns that have only become more relevant. Ledgard talks about "Gal," the synthetic skin he’s developing through transgenesis. He mentions using pig DNA. Back in 2011, this sounded like pure sci-fi.

Fast forward to today. We are seeing massive leaps in lab-grown organs and CRISPR gene editing. Almodóvar wasn't trying to write a documentary, obviously. He was tapping into the perennial human fear: just because we can engineer the body, should we? The film argues that no matter how much you change the exterior—the "skin"—the "inhabitant" remains. Identity isn't something that can be cut away with a scalpel.

The Banderas Evolution

This was the role that reminded the world why Antonio Banderas is a powerhouse. Before this, he’d spent a lot of time doing Puss in Boots and American action flicks. In la piel que habito pelicula, he is terrifyingly still.

📖 Related: New Movies in Theatre: What Most People Get Wrong About This Month's Picks

Robert Ledgard is a man who has replaced his soul with a checklist. He is polite. He is handsome. He is wealthy. And he is a monster. Banderas plays him with a chilling lack of empathy, making the moments where his composure cracks even more effective. It’s a performance of restraint. He doesn't twirl a mustache; he just adjusts his glasses and looks at a screen.

The Legacy of a Polarizing Ending

The final act of the film is a sprint. When the truth is revealed through a series of non-linear flashbacks, the audience is forced to grapple with their own sympathies. Do we feel bad for the "victim" even after we learn who they were before the surgery? It’s a messy, uncomfortable question.

Critics were divided at the time. Some felt the gender politics were regressive or shock-heavy. Others saw it as a profound statement on the fluidity and resilience of the human spirit. Personally? I think it’s Almodóvar’s most "perfect" film in terms of construction. Every frame serves the reveal.

Actionable Insights for Your Next Watch

If you're planning to revisit this or watch it for the first time, keep these things in mind to get the most out of the experience:

Pay attention to the screens. Ledgard watches Vera through massive surveillance monitors. This isn't just about control; it's about the "male gaze" taken to its most literal, voyeuristic extreme. He doesn't love her; he loves the image of her he created.

👉 See also: A Simple Favor Blake Lively: Why Emily Nelson Is Still the Ultimate Screen Mystery

Notice the color red. In Almodóvar’s world, red usually signifies passion or life. Here, it’s often associated with blood and the "raw" state of the body under the skin. It’s visceral.

Look at the yoga. Vera spends much of her captivity practicing yoga. It’s her only way to control her own body when everything else has been taken. It’s a silent act of rebellion. It shows that while her skin has been changed, her mind is working on a different plane entirely.

Research the source material. If you really want to go down the rabbit hole, read Tarantula by Thierry Jonquet. It’s even darker and more nihilistic than the film. Seeing how Almodóvar "humanized" certain elements while keeping the core cruelty intact is a fascinating study in adaptation.

The brilliance of la piel que habito pelicula is that it refuses to give you an easy out. It doesn't end with a neat moral. It ends with a confrontation. It’s a movie about the things we hide, the things we show, and the impossible task of truly owning another person. You don't just watch this movie; you survive it.