Humans are obsessed with the sky. We spend billions to peer at distant galaxies, yet we’ve barely scratched the skin of our own planet. It’s kinda wild when you think about it. If Earth were an onion, we haven't even broken through the first layer of papery skin. But back in the 1970s, a group of Soviet scientists decided to see how far they could actually go. They spent decades drilling a hole in the remote Arctic wasteland of the Kola Peninsula. This project, known as the Kola Superdeep Borehole, remains the deepest man-made point on Earth. It isn't a wide chasm or a gaping cavern. Honestly, it's basically just a nine-inch wide hole that goes down roughly 7.5 miles. That’s 12,262 meters, to be exact.

You’ve probably heard the rumors. People online love the "Well to Hell" story—the idea that scientists lowered a microphone and heard the screams of the damned. Let’s be real: that’s total nonsense. It was a hoax fueled by 1980s tabloid culture. The reality of what they actually found down there is way more interesting than a ghost story. They found water where it shouldn't exist. They found microscopic fossils at depths that defied logic. And eventually, they hit a wall of heat that turned the rock into something resembling plastic.

Why the Kola Superdeep Borehole was a Geologic Nightmare

Drilling a hole this deep isn't like digging in your backyard. You can't just use a standard rig and hope for the best. The Soviet team had to invent entirely new ways of boring through the Earth's crust. They used the Uralmash-4E, and later the Uralmash-15000 series, which were absolute beasts of machines. Most drill rigs rotate the entire pipe string to turn the bit at the bottom. But when your pipe is over seven miles long? Yeah, that doesn't work. The weight alone would snap the steel like a dry twig.

Instead, they used a "turbodrill." This clever bit of tech used the drilling mud itself—pumped down under immense pressure—to spin the drill bit at the bottom while the rest of the pipe stayed still. It was genius. But even with the best tech, the Kola Superdeep Borehole was a slow grind. They started in 1970. They didn't hit the 12,262-meter mark until 1989. Think about that timeline. Nineteen years of grinding through ancient Precambrian granite.

The heat was the real killer.

Geologists expected the temperature at 12 kilometers to be around 100°C (212°F). They were dead wrong. It was actually closer to 180°C (356°F). At that temperature, the rock stops behaving like a solid. It becomes "plastic." Every time they pulled the drill bit up to replace it, the hole would start to ooze shut behind them. It was like trying to maintain a hole in a jar of warm peanut butter. This heat eventually forced them to stop in 1992. They wanted to go to 15,000 meters, but the Earth simply wouldn't let them.

The Myth of the "Screams from Hell"

We have to address the elephant in the room. If you search for the Kola Superdeep Borehole on YouTube, you’ll find audio clips claiming to be recordings of human screams from the bottom of the pit.

📖 Related: Why the CH 46E Sea Knight Helicopter Refused to Quit

It’s a fake.

The "Well to Hell" legend started in 1989 when a Finnish newspaper published a story based on a letter to the editor. It claimed the scientists were terrified because they broke into a hollow cavity and heard suffering souls. The audio used in those viral videos? It’s actually a looped and pitch-shifted soundtrack from the 1972 horror movie Baron Blood. Science is rarely that cinematic. The real "sounds" of the borehole were seismic readings and the rhythmic thumping of industrial machinery.

What the Scientists Actually Found (The Real Gold)

Strip away the myths, and the data from the Kola Superdeep Borehole fundamentally changed how we view the planet's anatomy. One of the biggest shocks involved the "Conrad Discontinuity." For years, geologists believed there was a transition from granite to basalt at about seven kilometers deep. This was based on how seismic waves traveled through the Earth.

But when the Kola drill bit reached that depth?

Nothing.

No basalt.

Just more granite. It turns out the seismic change wasn't caused by a different type of rock. It was caused by the granite being crushed under such intense pressure that its physical properties changed. This forced scientists to rethink the entire crustal model.

Then there was the water.

👉 See also: What Does Geodesic Mean? The Math Behind Straight Lines on a Curvy Planet

Conventional wisdom said that water couldn't exist that deep. The pressure should have squeezed it all out. Yet, the team found fractured rock saturated with water. This wasn't groundwater that leaked down from the surface. This was "juvenile" water—hydrogen and oxygen atoms squeezed out of the rock crystals themselves by the crushing weight of the crust. Because of a layer of impermeable rock above it, this water had been trapped there for billions of years.

And the fossils? That’s arguably the coolest part. They found microscopic plankton fossils six kilometers down. These tiny organisms were over two billion years old. Finding organic remains that deep, encased in rock that had survived eons of tectonic shifting, was a massive win for biology. It showed that life, or at least the evidence of it, is incredibly resilient.

Other Contenders: Is Kola Still the Deepest?

Technically, yes and no. It depends on how you measure "deep."

In terms of vertical depth—meaning the distance from the surface straight down toward the core—the Kola Superdeep Borehole is still the undisputed king. No one has gone deeper into the Earth's "skin" vertically.

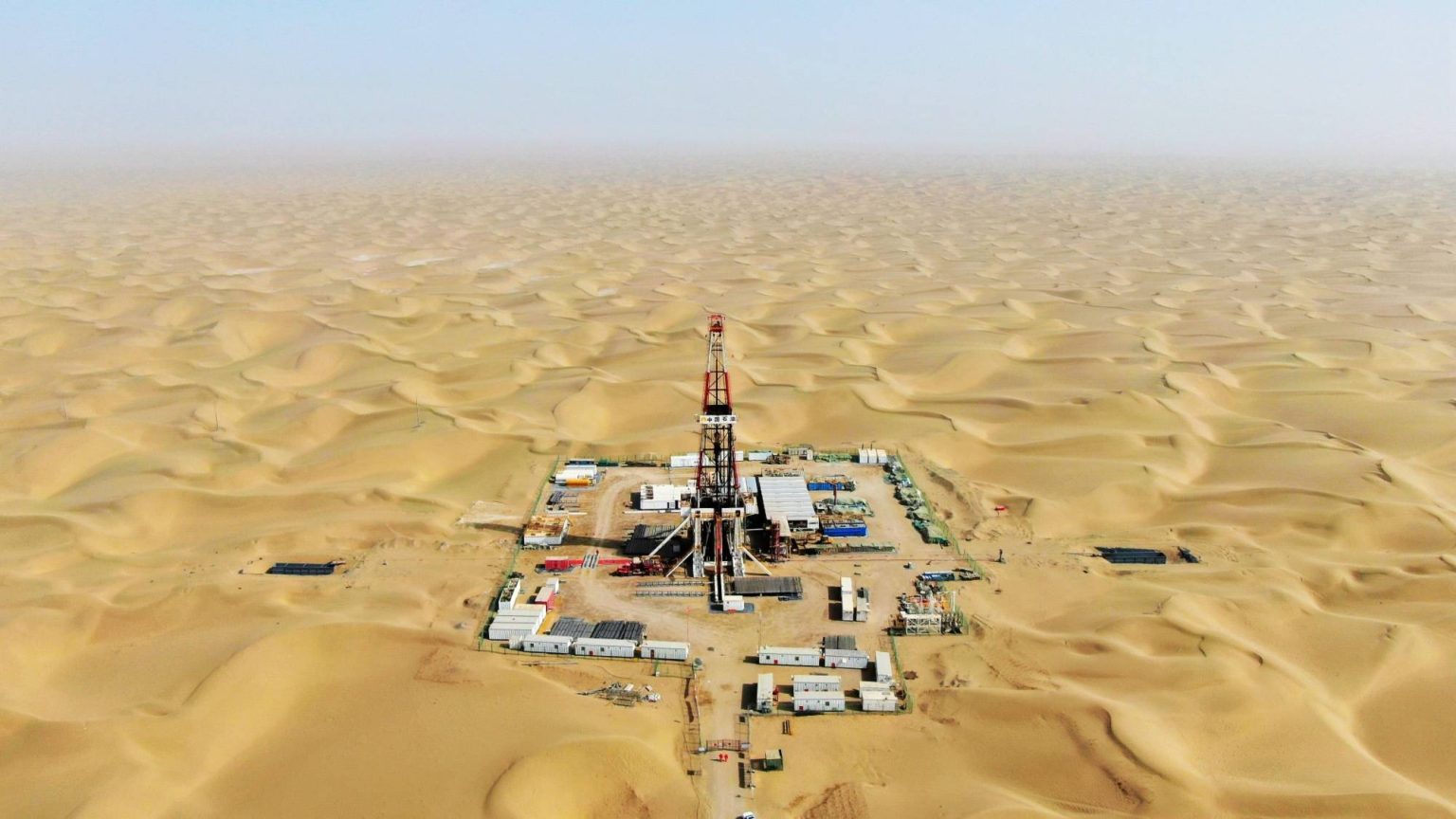

However, in the world of oil and gas, there are "longer" holes.

- The Al Shaheen Oil Well (Qatar): This reached a measured length of 12,289 meters in 2008.

- The Sakhalin-I Project (Russia): Several wells here have exceeded 12,000 and even 13,000 meters in total length.

But here’s the catch: these are directional wells. They go down a bit and then turn sideways to follow oil deposits. If you measured them vertically, they wouldn't even come close to Kola. Kola was a pure scientific flex. It was about going down, not out.

✨ Don't miss: Starliner and Beyond: What Really Happens When Astronauts Get Trapped in Space

The Abandoned Site and the "Rusty Cap"

If you visited the site today, you’d be disappointed. The Kola Peninsula is a bleak, subarctic environment. The once-massive laboratory and drilling complex is now a crumbling ruin. The Soviet Union collapsed, funding dried up, and the project was officially shuttered in the mid-2000s.

The hole itself?

It’s covered by a heavy, rusted metal cap held down by twelve massive bolts.

Some locals call it the "Gate to Hell," but mostly it’s just a graveyard of 20th-century ambition. The 12,262-meter hole is reportedly welded shut. You could walk right over it and never know you were standing above the deepest point ever touched by humanity.

Why Don't We Drill Deeper Now?

You’d think with 2026 technology, we could smash the Kola record easily. We have better materials, better cooling systems, and more computing power. But the cost-to-reward ratio is brutal. Drilling that deep costs hundreds of millions of dollars.

There are active projects, though. The Japanese drilling ship Chikyū has been trying to drill through the ocean floor to reach the mantle. Since the crust is much thinner under the ocean (about 5-10 km) than on land (about 30-50 km), it’s a "shortcut." But even then, the technical hurdles are insane. Deep-sea drilling adds the pressure of the entire ocean on top of the pressure of the rock.

Actionable Insights: Learning More About the Deep Earth

If the Kola Superdeep Borehole piques your interest, don't just stop at the "screams" legend. There's a lot of real science you can explore to understand what's happening under your feet.

- Visit a Core Library: Many geological surveys (like the USGS in the US or the BGS in the UK) have "core libraries" where you can actually see and touch rock samples pulled from deep underground. It's a surreal experience to touch something that hasn't seen the light of day for a billion years.

- Follow the "MoHole" Successors: Keep an eye on the International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP). They are the ones currently pushing the boundaries of deep-crust drilling. They provide regular updates on their expeditions to reach the Mohorovičić discontinuity (the boundary between the crust and the mantle).

- Use Real-Time Seismic Apps: Download an app like QuakeFeed or check the IRIS Seismic Monitor. These show you where the Earth is "moving" in real-time. Most of these quakes happen at depths similar to or deeper than Kola, giving you a sense of the activity happening in that 10km-20km "active zone."

- Check the Physics of Materials: Look up "rheology." It’s the study of how solids flow. Understanding how granite turns into a plastic-like state at high temperatures explains why the Kola team had to stop, and why we haven't gone deeper yet.

The Kola Superdeep Borehole is a reminder of our limits. We can build rockets that leave the solar system, but we are still humbled by the heat and pressure of our own home. It’s a 12-kilometer monument to human curiosity—a tiny, deep needle prick on a planet we are still trying to understand.