You’ve probably seen the posters. A rugged guy in a fedora, a beautiful woman in a torn dress, and some vaguely ancient-looking treasure. If you think that sounds a lot like Indiana Jones, you're right, but honestly, it’s the other way around. George Lucas and Steven Spielberg basically built Indy’s DNA from the bones of H. Rider Haggard’s 1885 novel and the subsequent King Solomon's Mines movie adaptations.

There isn't just one film. Depending on when you were born, your version of Allan Quatermain might be a dignified Victorian gentleman, a sweaty Stewart Granger, or a Richard Chamberlain who looks like he’s trying way too hard to be Harrison Ford.

The 1950 Technicolor Titan

Most film historians will tell you that the 1950 version starring Stewart Granger and Deborah Kerr is the gold standard. It was a massive swing for MGM. They didn’t just build a set in Burbank; they actually went to Africa.

This was 1950.

🔗 Read more: Why Room Taken Short Film Is Actually the Best Thing You’ll Watch Today

Think about the logistics of hauling massive Technicolor cameras through Kenya and Uganda back then. It was a nightmare. But that authenticity is exactly why it won the Academy Award for Best Cinematography. The colors are so vibrant they almost hurt your eyes.

One thing people often forget: this movie basically invented the modern "safari" aesthetic. Before this, adventure movies looked like they were filmed in a botanical garden in London. The 1950 film showed audiences the actual scale of the Serengeti.

Where it strayed from the book

Haggard’s original novel didn’t have a female lead. It was a "boys' club" adventure about three men looking for a lost brother. MGM knew that wouldn't sell tickets in the 50s, so they invented Elizabeth Curtis (Deborah Kerr).

The chemistry between Granger and Kerr is palpable, mostly because they were reportedly having a real-life affair during the shoot. It adds a layer of tension that you just can't fake with CGI.

That Bizarre 1985 Version (And Sharon Stone)

If the 1950 version is a fine wine, the 1985 King Solomon's Mines movie is a neon-colored soda that’s gone a bit flat. Cannon Films produced it. If you know anything about Cannon, you know they loved two things: low budgets and high action.

They hired Richard Chamberlain, fresh off The Thorn Birds, to play Quatermain. They also cast a then-unknown Sharon Stone as the female lead.

Stone has famously described the production as a "nightmare." They filmed in Zimbabwe, and the set was chaotic. The tone of the movie is all over the place. One minute it’s a slapstick comedy, the next there are Nazis (who weren't in the book, obviously, since it was written in 1885).

Critics absolutely hated it.

Yet, it has this weird, kitschy charm today. It’s a time capsule of the 80s trying to capitalize on the Raiders of the Lost Ark craze. If you want to see Sharon Stone almost get boiled in a giant pot by cannibals, this is your movie. Just don't expect a masterpiece.

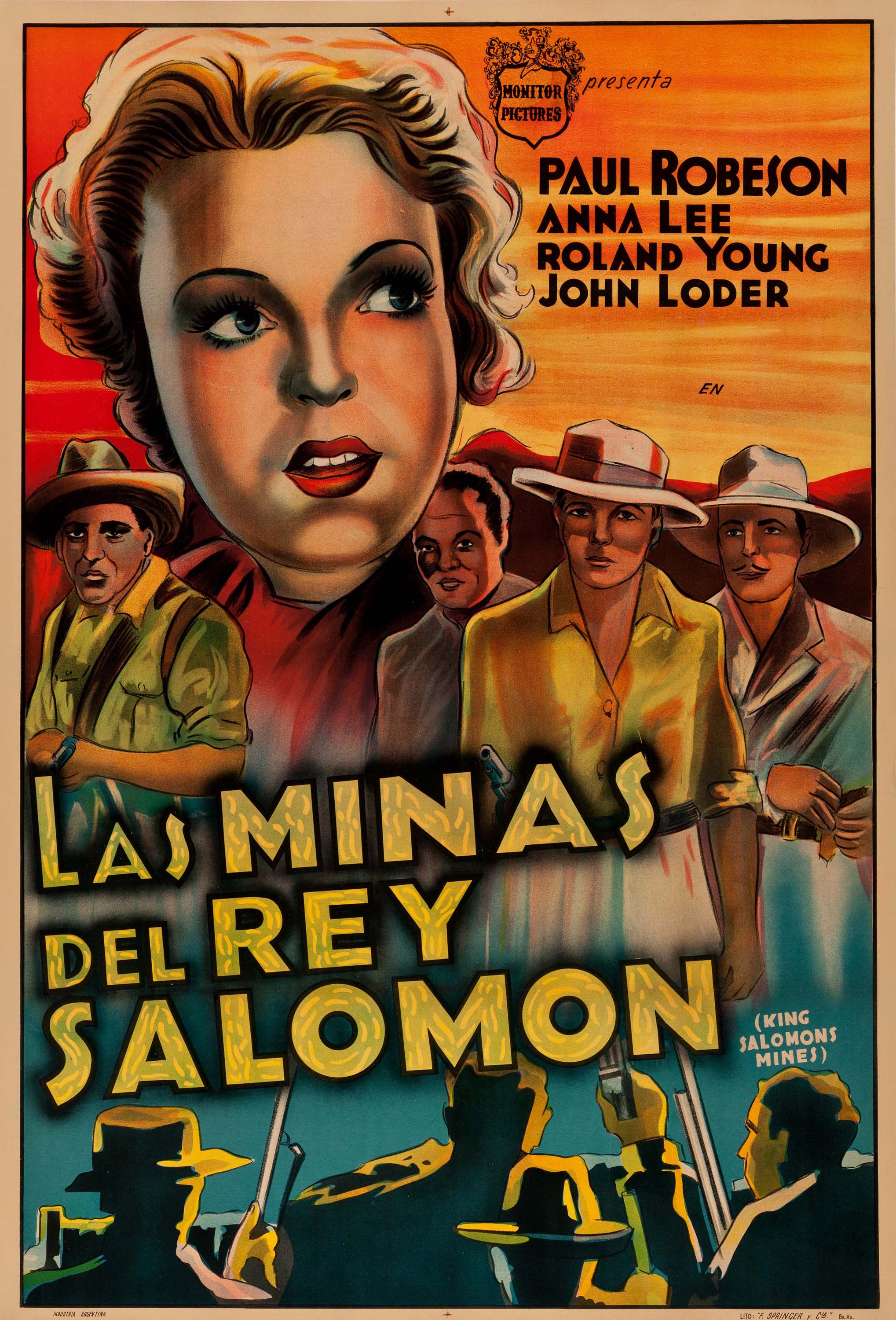

The 1937 Faithful Original

Hardcore fans of the book usually point to the 1937 British version as the most accurate. It stars Cedric Hardwicke as Quatermain and, more importantly, the legendary Paul Robeson as Umbopa.

🔗 Read more: Schitts Creek Christmas Episode: Why It Matters More Than You Think

Robeson was a powerhouse.

In a time when black actors were usually relegated to background roles, Robeson’s Umbopa is the moral center of the film. He’s a king in exile, and he carries himself with more dignity than the treasure hunters. It’s also one of the few versions that keeps the focus on the internal politics of the Kukuana people rather than just the diamonds.

Why Quatermain Isn't Just Indiana Jones

It's easy to dismiss Allan Quatermain as a "knock-off" Indy if you only see the 80s films. But Quatermain is a much darker character in the literature. He’s a big-game hunter who is world-weary and, frankly, a bit cynical about colonialism.

The movies usually scrub that away.

They turn him into a standard hero. But if you watch the 2004 Patrick Swayze miniseries (which many categorize as a movie), you see a bit more of that grizzled, tired man. Swayze played him with a certain sadness that fits the book's vibe better than Chamberlain’s "smirking adventurer" routine.

The Legacy of the Mines

Why do we keep remaking this?

💡 You might also like: Alice Cooper From the Inside: Why This Rehab Record Still Hurts So Good

It’s the "Lost World" trope. We love the idea that there’s still something left to find. Whether it’s the 1919 silent film or the 2004 Swayze version, the core hook remains: three people, a map, and a mountain range called "Sheba's Breasts."

If you’re looking to watch a King Solomon's Mines movie this weekend, here is the breakdown of what to expect:

- The 1950 Version: Best for spectacle, cinematography, and "classic Hollywood" vibes.

- The 1937 Version: Best for fans of the original book and Paul Robeson’s performance.

- The 1985 Version: Best for a "bad movie night" with friends or 80s nostalgia.

- The 2004 Version: Best if you want a longer, more character-driven story with Patrick Swayze.

To truly appreciate the evolution of the adventure genre, start with the 1950 film. It’s the bridge between the Victorian era of exploration and the modern blockbuster. Notice how the camera lingers on the landscapes; that wasn't just filler—it was the first time most of the world had ever seen those horizons in color.

Before you press play, keep in mind that these films are products of their time. The 1950 version is breathtaking but carries the colonial baggage of its era. The 1985 version is goofy but reflects the "Indy-cloning" of the 80s. Understanding that context makes the viewing experience a lot more interesting.

Check your streaming services for the 1950 Technicolor restoration—it's the version that holds up the best on modern 4K screens.