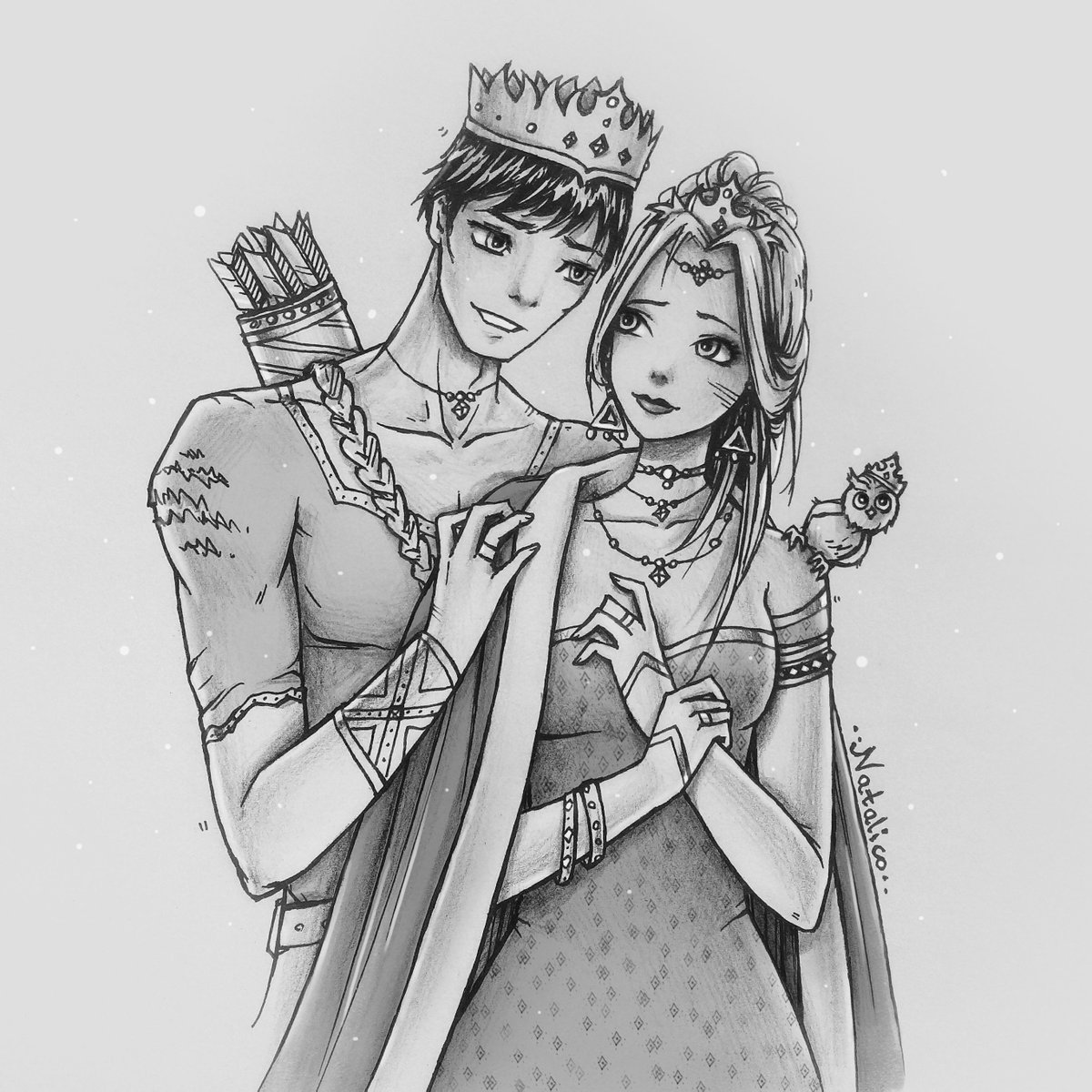

You've probably been there. You sit down with a fresh sheet of paper, a 2B pencil, and a vision of a regal couple—sharp jawlines, flowing velvet, and crowns that actually look like heavy gold instead of jagged cartoons. Then you start. Ten minutes in, your king looks like a grumpy chess piece and the queen’s proportions are so far off she looks like she’s melting into her cape. It’s frustrating. Honestly, king and queen drawing is one of the hardest things to master because you aren't just drawing people; you're drawing symbols of power, history, and very specific textures.

The mistake most people make is focusing on the "royalty" part first. They spend an hour on the tiny jewels in the crown while the face underneath has no bone structure. If the anatomy is wonky, the most expensive-looking crown in the world won't save the piece. To make a king and queen look truly majestic, you have to understand the interplay between rigid structure—the crowns and armor—and the fluid drape of royal garments.

The Core Geometry of a King and Queen Drawing

Stop thinking about characters. Think about shapes. Historically, a king is often depicted with a more rectangular, grounded silhouette to represent stability. Think of a heavy block. In contrast, queenly figures in classical art often utilize triangular compositions, especially with wide Tudor-style skirts or long trains. This creates a visual balance when you put them together.

If you look at the works of Hans Holbein the Younger, specifically his portrait of Henry VIII, the king is basically a giant square. It screams "I am immovable." When you're sketching, start with those primitive shapes. Don't worry about the nose yet. Get the shoulders wide. For the queen, focus on the "S" curve of the spine if she's standing, or a broad pyramid if she’s seated.

Proportions are your best friend here. A common pitfall is making the crowns too small. A real crown has weight. It should slightly compress the hair or sit firmly against the brow. If it’s just floating on top of the head, the drawing feels like a costume party, not a portrait. Draw the head first, then "wrap" the crown around it using elliptical guides to show depth.

Crowns Aren't Just Spiky Hats

We need to talk about the metal. Gold reflects the environment differently than silver or steel. In a king and queen drawing, the crown is your focal point, but it shouldn't be a solid yellow mass.

✨ Don't miss: Deep Wave Short Hair Styles: Why Your Texture Might Be Failing You

Real gold has deep burnt umber shadows and almost white highlights. If you’re working with graphite, the contrast needs to be extreme. Use a kneaded eraser to "pull" highlights out of the dark areas to simulate the glint of light hitting a polished surface.

Also, look at the "fleurs-de-lis" or the cross patterns. They aren't flat. They have thickness. Treat each spoke of the crown like a 3D object. One trick many professional illustrators use is to draw the negative space between the crown's points first. It helps you see the actual shape of the metal rather than what your brain thinks a crown looks like.

Fabric, Fur, and the Weight of Power

You can’t have royalty without ermine and velvet. Velvet is tricky because it absorbs light in the folds and reflects it on the ridges. It’s the opposite of silk. For the "king and queen drawing" aesthetic, you want those deep, heavy folds.

- Ermine fur: That iconic white fur with black spots isn't just a pattern. The black spots are actually the tails of the stoats. They should follow the contour of the drape. If the cloak folds, the spot should disappear into the fold or tilt.

- Velvet: Use a soft 4B or 6B pencil. Don't blend it too much with your finger; use a paper stump or a tissue to get that soft, diffused look.

- Jewelry: Each gem is a tiny mirror. A ruby isn't just red; it has a dark core and a bright "spark" where the light hits.

Why Facial Expression Changes Everything

A king and queen shouldn't always be smiling. If you look at 16th-century royal portraiture, the goal was "gravitas." You want a look of controlled power. This usually means a neutral mouth and eyes that are slightly hooded.

For the king, emphasize the brow bone. It adds a sense of sternness or wisdom. For the queen, focus on the neck and the "proud" tilt of the chin. Even a slight 5-degree upward tilt changes the entire vibe from "person in a dress" to "monarch of the realm."

🔗 Read more: December 12 Birthdays: What the Sagittarius-Capricorn Cusp Really Means for Success

Kinda weirdly, the hands are just as important as the face. A king gripping a scepter should show tension in the knuckles. A queen holding a rose or a fan should show elegance through elongated fingers. If the hands look like sausages, the royal illusion is shattered.

Composition: Putting the Pair Together

When drawing both figures, you have to decide on their relationship. Are they equals? Is one slightly in front? In the famous portraits of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, the composition often subtly pointed toward Victoria’s status as the regnant monarch, even if they were posed affectionately.

Try overlapping them. Having the king’s cloak partially cover the edge of the queen’s dress creates a sense of unity. If they are standing side-by-side with a gap between them, it can look like two separate drawings pasted together. Use the background—maybe a heavy curtain or a stone archway—to frame them and pull the eyes toward the center of the page.

Common Blunders to Avoid

- The Floating Crown: Already mentioned, but it’s the #1 killer of good drawings.

- Generic Features: Don't just draw two "pretty" people. Give them character. A scar, a slightly crooked nose, or heavy eyelids makes them feel like real historical figures.

- Flat Capes: If the cape doesn't have shadows that match the light source, it looks like a piece of paper stuck to their backs.

- Symmetry: Human faces aren't perfectly symmetrical. Neither should their clothes be. Let one side of the cloak hang a bit lower. It adds realism.

Honestly, the best way to get better at this is to look at real historical artifacts. Go to the digital archives of the British Museum or the Louvre. Look at how the light hits the "Imperial State Crown." Notice that the metal isn't just a line; it has thickness and texture.

Actionable Steps for Your Next Sketch

Start by sketching just the "armature"—the basic stick figure—but with the wide shoulder line for the king and the bell-shape for the queen. Use a light H pencil for this so you can erase it easily later.

💡 You might also like: Dave's Hot Chicken Waco: Why Everyone is Obsessing Over This Specific Spot

Once you have the frame, map out the "anchor points" of the clothing. Where does the heavy fabric hang from? Usually the shoulders and the waist. Draw the "tension lines" where the fabric pulls.

For the crowns, draw a circle that fits around the head like a sweatband. This ensures the crown follows the perspective of the skull. Then, build the decorative elements on top of that circle.

When you get to the shading, pick a single light source. If the light is coming from the top left, every jewel, every fold of the cape, and every point on the crown must have its shadow on the bottom right. Consistency is what makes the drawing look "professional" rather than "amateur."

Finally, don't be afraid of the darks. Many artists are scared to make their shadows truly black. If you're doing a king and queen drawing, you need that high-contrast drama. Use your softest pencils and really push those deep shadows in the velvet folds. It'll make the highlights on the gold pop twice as much.

The difference between a doodle and a masterpiece is often just the willingness to go back and refine the small details that signal status—the lace at the cuff, the reflection in a signet ring, or the way a heavy robe bunches at the floor. Keep your pencil sharp and your references closer.

Next Steps for Mastering the Royal Aesthetic:

- Study Drapery: Spend 20 minutes sketching a heavy towel or blanket thrown over a chair. This mimics the weight of a royal mantle.

- Master the Ellipse: Practice drawing circles in perspective. Since crowns, rings, scepters, and necklines are all circular, being able to draw a perfect ellipse is non-negotiable.

- Reference Real Metal: Find a gold ring or a brass spoon. Shine a desk lamp on it. Notice how the "highlight" is often right next to the darkest "shadow." This is the secret to drawing metallic crowns that look real.

- Work on Facial Gravitas: Practice drawing "neutral" expressions that still convey emotion through the eyes. Study the "Mona Lisa" or the portraits of Velázquez to see how subtle muscle movements around the eyes change a character's perceived authority.