You’re standing at the top of a hill on a bicycle. Everything is quiet. But the second you nudge that front tire forward and start rolling, something invisible takes over. That’s not magic. It’s the meaning of kinetic energy in physics coming to life.

Basically, if it moves, it has it.

If you’ve ever wondered why a ping-pong ball feels like a tickle but a bowling ball at the same speed feels like a broken toe, you’re already poking at the heart of classical mechanics. Energy isn't just some abstract "juice" that powers things. In the world of physics, kinetic energy is specifically the work an object can do because of its motion. It's the byproduct of effort.

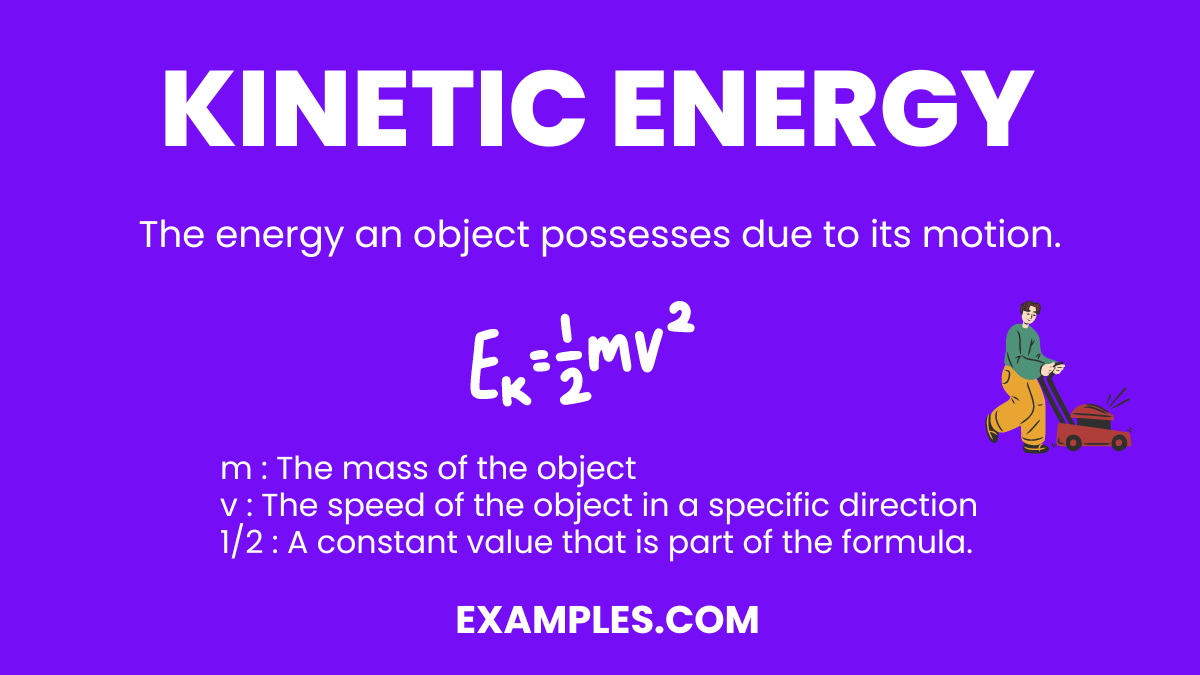

The Core Meaning of Kinetic Energy in Physics

At its most raw level, kinetic energy is the energy of mass in motion. But let’s get specific. It’s defined as the work needed to accelerate a body of a given mass from rest to its stated velocity. Once an object gains this energy during acceleration, it maintains it unless its speed changes.

Most people think energy is just "there," but physics tells us it's a ledger. You can't have motion without a transaction. To get a 1,500kg car moving at 60 mph, you have to burn fuel to perform work. That work doesn't vanish; it "lives" in the car’s velocity. If that car hits a wall, the wall has to do an equal amount of work to stop it—usually by crumpling metal and generating heat.

The standard formula—and yeah, we have to look at the math for a second—is:

$$K.E. = \frac{1}{2}mv^2$$

Here, $m$ is mass and $v$ is velocity. Notice that the velocity is squared. That’s huge. It means if you double your speed, you don't just double your energy. You quadruple it. This is why car crashes at 70 mph are significantly more lethal than those at 35 mph. It's not a linear jump; it’s exponential.

Why Mass and Speed Aren't Created Equal

Have you ever watched a freight train crawl along at five miles per hour? It looks slow. You could probably jog faster. But if that train hits a car parked on the tracks, the car is deleted. Why? Because the mass ($m$) is so gargantuan that even a tiny velocity ($v$) results in massive kinetic energy.

On the flip side, consider a bullet.

A 9mm bullet weighs almost nothing—roughly 7.5 grams. That’s about the weight of three pennies. Yet, because it travels at 380 meters per second, that $v^2$ part of the equation does some heavy lifting. The velocity "wins" over the tiny mass, resulting in enough energy to punch through steel.

Physics is always a trade-off between these two variables. You’ve got the heavy-and-slow camp (glaciers, cruise ships) and the light-and-fast camp (photons, electrons, bullets). Both carry kinetic energy, but they interact with the world in completely different ways.

The Three Flavors of Motion

We usually think of things moving in a straight line. That’s "translational" kinetic energy. But physics is rarely that simple. Molecules are vibrating. Planets are spinning. Baseballs are curving.

- Translational: This is the "A to B" movement. A sprinter running the 100m dash.

- Rotational: Think of a spinning top. It’s not "going" anywhere, but it’s definitely moving. The particles are orbiting a center point. A heavy flywheel in an engine stores energy this way.

- Vibrational: This happens at the atomic level. Even in a "still" object like a coffee mug, the atoms are wiggling. When you add more vibrational kinetic energy, we call that "heat."

Misconceptions That Trip People Up

A common mistake is confusing momentum with kinetic energy. They’re cousins, but they aren't the same. Momentum is $mv$. Kinetic energy is $1/2mv^2$.

Momentum is a vector—it has direction. Kinetic energy is a scalar. It doesn't care if you're going North, South, or doing a loop-de-loop; it only cares about the total magnitude. If two cars of equal mass crash head-on at the same speed, their total momentum might be zero at the moment of impact, but their total kinetic energy is definitely not zero. That energy has to go somewhere, and it usually goes into sound, heat, and the deformation of the chassis.

Another weird one? Frame of reference.

If you’re sitting on a plane going 500 mph, you might think your kinetic energy is zero because your coffee isn't spilling. To you, it is zero. But to someone standing on the ground watching you fly over, you have a massive amount of kinetic energy. Physics is relative. The meaning of kinetic energy in physics depends entirely on who is doing the measuring.

Real-World Stakes: Engineering and Safety

Engineers spend their lives obsessed with managing kinetic energy.

Take the "crumple zone" in your car. Before the 1950s, cars were built like tanks. They were rigid. People thought that was safer. It wasn't. When a rigid car hits a wall, the kinetic energy stops almost instantly ($v$ goes to 0 in a fraction of a second). Because the car doesn't move, that energy is transferred directly to the passengers' internal organs.

📖 Related: Reinforced Hose Abiotic Factor: Why Your Setup is Failing Under Pressure

Modern cars are designed to "fail" elegantly. By crumpling, the car extends the time it takes for the velocity to reach zero. This dissipates the kinetic energy over a longer period, reducing the force felt by the humans inside.

In the world of green energy, wind turbines are essentially giant kinetic energy harvesters. They take the translational kinetic energy of air molecules (wind) and convert it into rotational kinetic energy (the blades), which then turns a generator to create electrical energy. It's all one big game of "pass the baton."

Relativistic Kinetic Energy: When Classical Physics Breaks

For most of human history, $1/2mv^2$ was the law of the land. Then Einstein showed up.

When things start moving really fast—like, close to the speed of light fast—the old rules stop working. As velocity increases toward $c$ (the speed of light), the kinetic energy starts to grow much faster than the square of the velocity. It actually approaches infinity. This is why we can't push a physical object to the speed of light; it would require an infinite amount of work to get it there.

For us regular folks walking around on Earth, the classical Newtonian version is perfect. But for particle physicists at CERN, they have to use relativistic calculations to keep their experiments from blowing up.

Practical Insights for Your Daily Life

Understanding this isn't just for passing a test. It changes how you see the world.

- Braking Distance: Remember the $v^2$ rule. If you speed up from 30 mph to 60 mph, you need four times the distance to stop, not twice. Give yourself space.

- Sports Performance: In golf or baseball, it's not just about how heavy the club or bat is. It's about "clubhead speed." Increasing your swing speed has a much larger impact on the ball’s distance than using a heavier bat because of that squared velocity.

- Home Efficiency: Insulation is basically a barrier to stop the kinetic energy of air molecules from leaving your house. Keeping those molecules "jiggling" inside keeps you warm.

Next Steps for Deepening Your Knowledge

If you want to master this, stop looking at the formulas and start looking at the transitions.

Try this: Next time you see something stop suddenly—a ball hitting a wall, a car braking—ask yourself, "Where did the kinetic energy go?" It didn't disappear. Did it turn into sound (the "thud")? Did it turn into heat (the smell of burnt rubber)?

Once you start seeing the world as a series of energy hand-offs, physics stops being a textbook subject and starts being a lived reality. Check out resources like the Feynman Lectures on Physics for a deeper look at how energy conservation works across different scales. You can also experiment with simple simulations on sites like PhET Interactive Simulations to see how changing mass versus velocity alters the energy output in real-time.