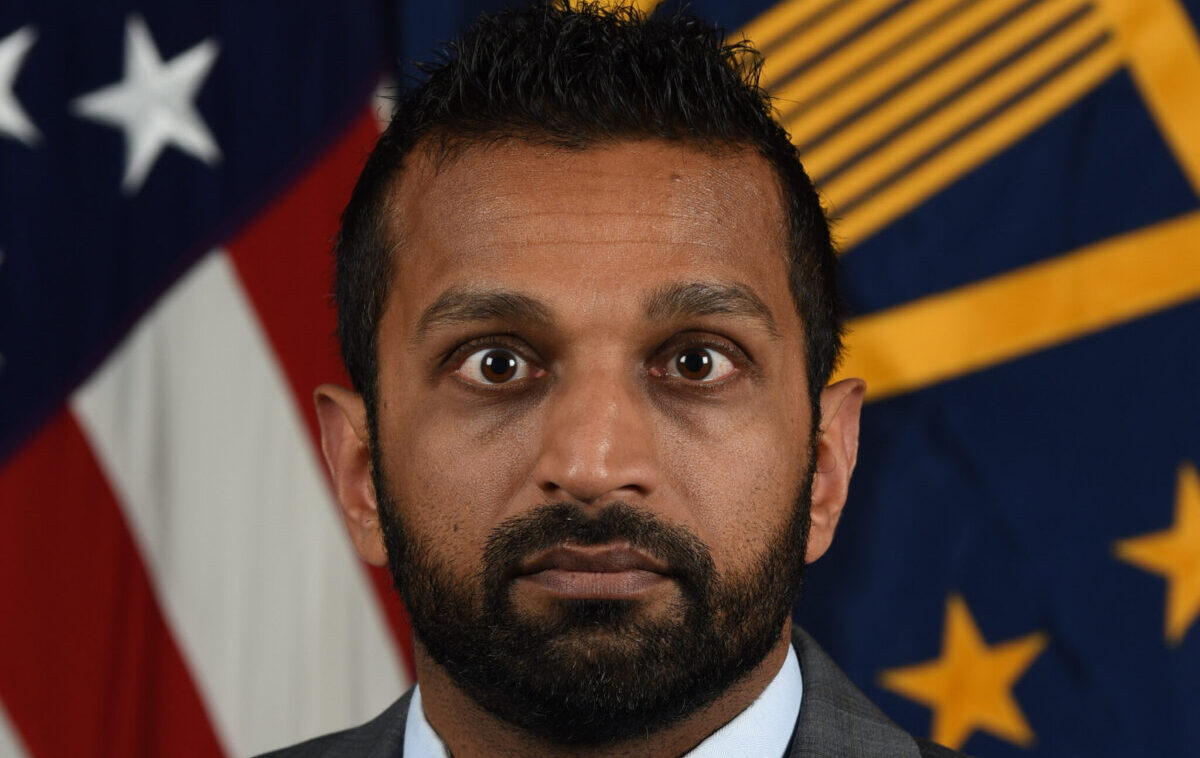

When FBI Director Kash Patel touched down in Wellington in July 2025, the vibe was supposed to be all about "strengthening the Five Eyes alliance." He was there to cut the ribbon on the FBI’s first-ever standalone office in New Zealand. Pretty standard diplomatic stuff, right? But the trip took a weirdly cinematic turn when Kash Patel gifts New Zealand officials something that actually broke the law.

We aren't talking about classified documents or secret briefcases. We're talking about plastic. Specifically, 3D-printed replica pistols.

These weren't just loose toys tossed across a table. They were mounted on "challenge coin" display stands—the kind of commemorative plaques you see in high-level military and intelligence circles. But for New Zealand, a country that transformed its relationship with firearms after the 2019 Christchurch tragedy, these gifts weren't seen as cool desk accessories. They were seen as illegal weapons.

The Maverick PG22: A Toy-Like Problem

The specific model Patel handed out was the Maverick PG22. If you follow the 3D-printing scene, you might recognize the name. It’s a revolver design that’s actually modeled after a Nerf gun—bright colors and all. Honestly, it looks like something a kid would play with in the backyard.

But here’s the kicker: the Maverick PG22 is a notorious "working" 3D-printed gun. Even though the versions Patel gifted were supposedly "inoperable," New Zealand law doesn't really care about your intentions.

✨ Don't miss: Who Is More Likely to Win the Election 2024: What Most People Get Wrong

Under the local Arms Act, if a replica can be modified to fire with "minimal skills and common handyperson tools," it’s a firearm. Period. And in New Zealand, pistols are high-tier restricted items. You don't just "get" one; you need a specific endorsement on your license that most people, even high-ranking officials, don't just carry around for fun.

Who exactly got these "illegal" gifts?

It wasn't just a single awkward exchange. Patel was busy. He presented these display stands to at least five of the most powerful people in New Zealand’s security apparatus:

- Richard Chambers: The Police Commissioner.

- Andrew Hampton: Director-General of the NZSIS (the spy agency).

- Andrew Clark: Director-General of the GCSB (the signals intelligence agency).

- Mark Mitchell: The Police Minister.

- Judith Collins: The Minister responsible for the military and spy agencies.

Imagine being the Police Commissioner and having the head of the FBI hand you something that you literally have to arrest people for owning. Chambers didn't mess around. The very next day, he sought advice from the Firearms Safety Authority. The verdict? The guns were potentially operable. They had to go.

"An Overreaction" vs. Strict Compliance

Not everyone thought the shredder was the right move. James Davidson, a former FBI agent and president of the FBI Integrity Project, called the destruction an "overreaction." He argued that the NZSIS could have just rendered them permanently inert instead of destroying the gesture entirely.

🔗 Read more: Air Pollution Index Delhi: What Most People Get Wrong

But you've got to understand the context. New Zealand’s gun culture is lightyears away from the U.S. version. In NZ, gun ownership is a privilege, not a right. Most beat cops don't even carry guns on their person; they keep them locked in the car. So, when the FBI director brings 3D-printed revolvers into a meeting, it doesn't read as "cool gear"—it reads as a massive compliance headache.

The Secretive Trip and Geopolitical Friction

The gift drama was actually just a side dish to a much larger geopolitical awkwardness. The opening of the FBI office wasn't even made public until after it happened.

While there, Patel made some pretty pointed comments about the need to "counter" the influence of the Chinese Communist Party in the South Pacific. This put New Zealand officials in a bit of a spot. They basically had to do a diplomatic "thanks, but no thanks" dance, emphasizing that the new FBI office was actually there to fight child exploitation and drug smuggling, not to start a regional proxy war with Beijing.

Beijing, predictably, wasn't thrilled. They issued a diplomatic protest, and the whole "gift-gate" thing just added another layer of "what was he thinking?" to the visit.

💡 You might also like: Why Trump's West Point Speech Still Matters Years Later

What happened to the guns?

They’re gone. Every single one of them.

Commissioner Chambers confirmed that he ordered the police to retain and destroy the replicas. Interestingly, the police armory team actually asked if they could keep one of the Maverick PG22s for "testing and training" purposes, since it's one of the most common 3D-printed guns they seize on the streets. Chambers said no. He wanted them destroyed to ensure total compliance with the law.

The U.S. Embassy in Wellington eventually put out a statement saying they "supported" the decision and that the gift was "well-intentioned." It was a classic "let's just move past this" move.

Actionable Insights for International Relations

This whole situation is a masterclass in why cultural and legal "due diligence" matters in diplomacy. If you're looking at this from a business or legal perspective, here’s what you can take away:

- Local Law is King: Even if you're the head of a massive federal agency, you aren't exempt from the import laws of a sovereign nation.

- 3D Printing is a Legal Gray Area: Laws are still catching up to the tech. What looks like a plastic toy in one country is a felony in another.

- Context Matters: In a post-Christchurch New Zealand, any firearm—even a 3D-printed one on a trophy—is a sensitive symbol.

To stay updated on how these diplomatic ties are evolving, you should keep an eye on the official New Zealand Police and NZSIS annual reports, as they usually disclose high-level gift registers and foreign agency collaborations toward the end of the fiscal year. You can also monitor the U.S. Department of State’s "Office of the Chief of Protocol" gift listings, though those often have a significant lag time before they hit the public record.