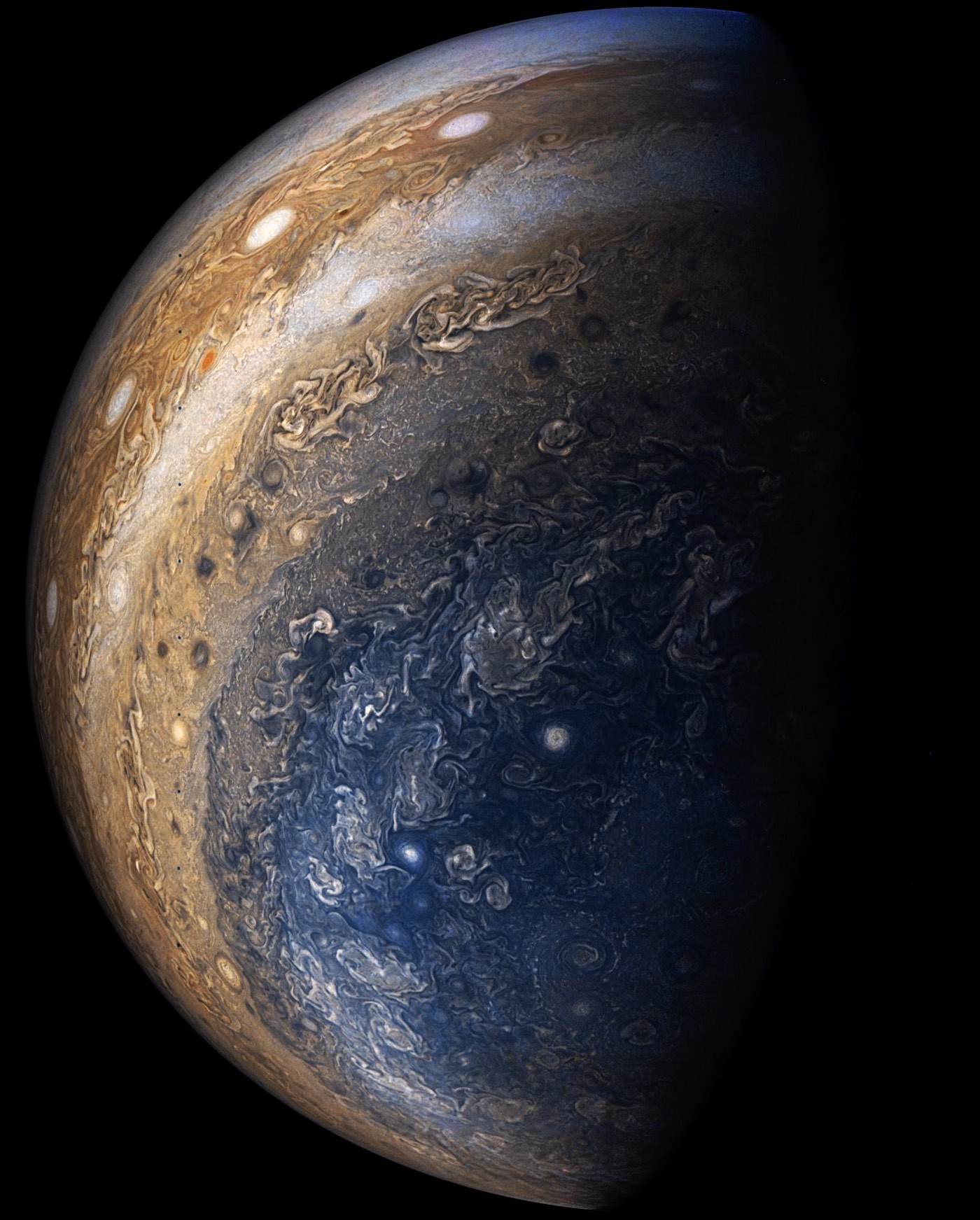

Jupiter shouldn't look like this.

When you see those swirling, psychedelic marble patterns in the latest juno probe jupiter images, it’s easy to assume a NASA artist just went wild with the "liquify" tool in Photoshop. Honestly? The reality is way weirder. We grew up looking at grainy, beige-and-red photos from the Voyager era, where the planet looked like a somewhat stable, striped ball.

Juno changed everything.

💡 You might also like: Sony Xperia Z3: What Most People Get Wrong About This Classic

Since it arrived in 2016, this titanium-shielded bus has been screaming past the gas giant in long, elliptical loops. It gets close—really close. We’re talking 2,100 miles from the cloud tops. For a planet that’s 88,000 miles wide, that’s basically a haircut.

The "Fake" Color Debate

People always ask if the colors are real. The short answer? Kinda.

The JunoCam instrument is technically an "outreach" camera. It wasn't even part of the original core science payload. NASA basically said, "Hey, the public might want to see some pictures," and slapped it on. But here’s the kicker: NASA doesn't have a giant team of "space photographers" processing these. They dump the raw data—which looks like a gray, distorted mess—onto a public server.

Then, the "citizen scientists" take over.

Experts like Kevin M. Gill or Gerald Eichstädt spend hours de-stretching the data and pulling out the contrast. If you see an image where the storms look like a Van Gogh painting, that's "enhanced color." It’s meant to show you the chemical differences in the clouds that your naked eye wouldn't pick up. If you actually flew past Jupiter in a spaceship, it would look a lot more muted. Think creamy tans and soft browns.

But the "fake" colors tell the real story. The deep blues represent clear air or deep holes in the clouds. The bright whites are "pop-up" storms—massive towers of ammonia ice that poke up through the atmosphere like thunderheads on Earth.

What the 2025 and 2026 Images Revealed

As we moved through late 2025 and into the early months of 2026, the mission entered its twilight phase. The spacecraft is currently getting hammered by radiation. Jupiter’s magnetic field is a beast. It’s like a particle accelerator that never turns off.

💡 You might also like: Why Florida Institute of Technology Is Secretly a Space Coast Powerhouse

Every time Juno dives through those radiation belts, the hardware takes a hit.

Recent images from Perijove 69 (that’s just the fancy name for a close flyby) showed something amazing near the north pole. Instead of the stripes we see at the equator, the poles are a chaotic honeycomb of cyclones. We call them circumpolar cyclones.

There are nine of them.

They don't move. They just sit there, bumping into each other like bumper cars that never actually crash. It defies every weather model we had before the juno probe jupiter images started coming in. Why don't they merge into one giant super-storm? We still don't totally know.

Recent highlights from the gallery:

- Amalthea's Cameo: In late 2024, Juno caught a glimpse of the "potato moon," Amalthea. It looked like a tiny, reddish speck against the backdrop of Jupiter’s Great Red Spot.

- The Green Lightning: One of the most famous shots shows a green glow inside a dark vortex. That’s lightning. On Earth, lightning happens in water clouds near the equator. On Jupiter, it’s an ammonia-water slush happening mostly at the poles.

- The Great Red Spot's "Flaking": The latest shots confirm the GRS is still shrinking. It’s becoming more of a circle than an oval. Scientists used to think it was dying, but now they think the "flaking" seen in the images is just the storm eating smaller cyclones.

Looking Beneath the Hood

Juno isn't just a camera. It has a Microwave Radiometer (MWR) that "sees" deep into the planet.

We used to think Jupiter’s atmosphere was just a thin skin. Wrong. The storms we see in the juno probe jupiter images actually go deep. The Great Red Spot extends about 200 miles down. The "jets"—the winds that create the stripes—go down nearly 2,000 miles.

At that depth, the pressure is so high that the atmosphere starts acting like a solid. It rotates as one piece.

The most controversial discovery? The core. Scientists expected a solid rock. Instead, Juno’s gravity measurements suggest a "fuzzy" or "dilute" core. It’s like a giant ball of lead and rock that got smashed and dissolved into the hydrogen around it. This probably happened billions of years ago when a planet ten times the size of Earth slammed directly into Jupiter.

The End of the Road

NASA originally planned to crash Juno into Jupiter in 2021. They extended it. Then they extended it again.

But the clock is ticking.

The current plan has the spacecraft de-orbiting and burning up in Jupiter's atmosphere. Why kill it? To protect the moons. Europa and Ganymede might have underground oceans. If Juno eventually ran out of fuel and crashed into Europa, it could contaminate a pristine alien ocean with Earth bacteria.

NASA won't take that risk.

So, within the next year, Juno will become part of the planet it spent a decade studying. The final juno probe jupiter images will likely be high-speed blurs as the camera melts. It's a bit poetic, really.

How to Explore the Images Yourself

If you want to see the "real" Jupiter without the NASA press release filter, you can.

Go to the Mission Juno website. You can download the raw "strips" of data. They look like weird, elongated noodles because the camera takes pictures as the spacecraft spins.

If you're handy with GIMP or Photoshop, you can try processing them yourself. Most of the famous images you see on news sites were actually made by people sitting at home in their pajamas, not guys in lab coats at JPL.

What to do next:

If you're looking for a specific desktop wallpaper or just want to see the latest raw data from the current month, visit the JunoCam processing gallery. Search for "Perijove 68" or "Perijove 69" to see the newest files uploaded by the community. Check the "metadata" on the images to see the exact altitude—some of the shots from 2025 are from a distance of less than 5,000 miles, providing some of the highest-resolution views of the "Folded Filamentary Regions" ever recorded.